To kill a mocking monster

I am trying to get this image out of my head. Over a hundred people of all ages walked in to find their spots on a boat that would take them to the other side of the Korotoa River to celebrate Mahalaya. These pilgrims joined the herd in good faith – they must go to the temple to invite their goddess before she starts descending from Mount Kailash for the annihilation of the monster. They would also pay tribute to their dead ancestors. There was not an inch of empty space left on the boat. The boatman waded back and forth to check how his passengers had been tucked in. Some last-minute passengers touched the rim in reverence or sprinkled waters with piety before the boat set sail.

These were devotees in Panchagarh district, at the northern tip of Bangladesh, who had hired this boat to visit the Bodeshwari temple. Surprisingly, none of them – of the over a hundred pilgrims – pointed out how dangerous it was to travel like that. Not one soul protested saying, "I am not riding on this boat." They simply sailed to their deaths. Within minutes, the overcrowded boat capsized and most of the devotees perished; at least 68 bodies have been found so far, with many still missing.

What prompted them to join this death march? A belief that they would be taken care of by divine providence! The practical reason was that it was the best they could afford. Who in their right mind would like to see their money wasted? The Korotoa River had other plans, though. However tame it looked in autumn, it had no place for recklessness. Shouldn't I feel pity for these victims? Instead, I am upset by their blind foolishness. I am angry at those people at the shore who allowed them to dock dangerously and kept on recording the spectacle. I am angry at the relatives who came to see them off for not talking sense to these people. The accident shows how cheap our lives have become. What good is paying compensation per body? Use that money to improve transport quality and safety rules. Use it to educate people and inculcate common sense.

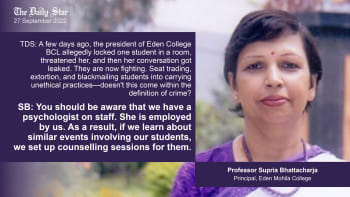

I am trying to get another image out of my head. Hundreds of female students of Eden Women's College were seen shouting and yelling, beating up one another, pulling at each other's hair, and banging on the iron gate in the middle of the night. The scene was raucous; I did not turn up my TV volume. A déjà vu. The allegations are serious and outright illegal: student leaders are allegedly engaged in seat-trading, extortion, torture, forcing other students to indulge in unethical activities, and controlling hostels and cafeterias. We have heard it before. The principal of the college told The Daily Star that previous investigations were still ongoing, and she now seeks psychological counsellors to change the students' mindsets.

My common sense tells me not to rock the boat carrying the Eves of Eden. They are no less mighty and lethal than their male colleagues, whom we have recently seen in full action. And the sad part is that the existential label that they are carrying and the jerseys that they are donning are but temporary. Their essential identity is tied with power politics. They blindly join the party vehicle with the hope of being blessed by some divine providence. This is a slow death of a different kind: the mass killing of a generation. And the worst part is that they devour the image of their founder, who struggled to give us freedom.

I am trying to get this image out of my head. After a hiatus from holding an administrative post at a private university, I resumed my job at the oldest university in the country. I am assigned a course named "Novels through Theory," wherein I am teaching Frankenstein, a multi-layered text from the 19th century written by a 19-year-old Mary Shelley. The author believed that she was responsible for the death of her mother, who died of postpartum infection. Mary Shelley, therefore, wanted the human race to continue without the need for biological birth that kills many women. Her science fiction involves creating a life without the need for a mother. She makes her male protagonist, Victor Frankenstein, bring dead bodies to come to life in his lab.

My feminist reading of the novel shows gender performativity to argue that gender roles are elaborate social performances that one puts on in their everyday life. It goes beyond the fixed conceptions of "man" as "masculine" and "woman" as "feminine." Victor is the "mother" of the creature, for instance.

I gave further examples of our national women's football team, whose valour at the Dasharath stadium in Kathmandu, Nepal earned the nation a coveted trophy that had been eluding their male colleagues for decades. These women manned the mission and came back as national heroes riding a roofless bus under the sky. Their performance was masculine. But when some of these girls were returning to their hometown in a public bus, they were verbally abused by some conservative men for their supposed "abnormal" gender performance in "skimpy" clothes. In that remote private space, the girls were reduced to being "stereotypical women."

As I said these words, I noticed a couple of students in my class shaking their heads with visible displeasure. The cue was obvious. I must be careful with my examples. Just like when giving one of the definitions of Frankenstein, I had to check myself from referring it to our student body. Frankenstein is "something that destroys or harms the person or people who created it." But the irony is: even Frankenstein, a wrongly attributed name given to the monstrous creature, wanted to learn. He read history, poetry, philosophy, and politics, and wanted to know himself before his self-annihilation for the sake of humanity. He realised that the purpose of life is to give meaning to it, not die meaninglessly, or become the cause of harm to others.

I am trying to get these meaningless images out of my head.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is a professor of English at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments