Ranking Realities : Bangladesh’s higher education strategy needs a redesign

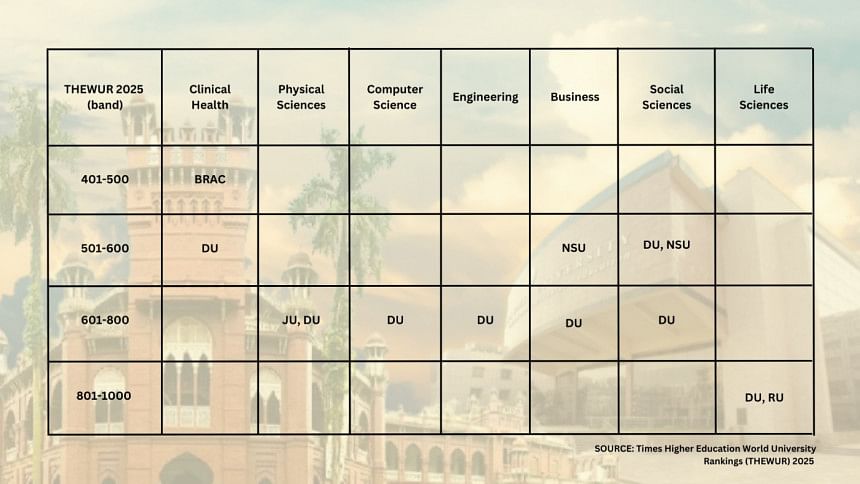

The announcement of university rankings has caused a considerable stir. For the cynics, the absence of any Bangladeshi university among the top 800 institutions recently ranked by Times Higher Education World University Rankings (THEWUR) 2025 is unacceptable. Optimists view the presence of five universities in the 801-1000 bracket as a significant achievement. There are four new entries in this category: Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University (BSMRAU), Jahangirnagar University, Daffodil International University (DIU), and Jashore University of Science and Technology (JUST), joined by North South University (NSU). This year, THEWUR found 2,092 universities eligible; 16 are from Bangladesh.

The position of the country's premier universities, including Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), Dhaka University (DU), Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU), and BRAC University, outside the 1000 list has raised some concerns. These three universities found themselves in the cohort of Rajshahi University (RU), Chittagong University of Engineering and Technology (CUET), and Khulna University of Engineering and Technology (KUET) in the 1001-1200 band. Chittagong University (CU), American International University of Bangladesh (AIUB), Rajshahi University of Engineering and Technology (RUET), and Khulna University (KU) are listed among the 1500 range, along with Jagannath University (JnU).

Ranking is an intricate process. Each ranking agency uses its own parameters, which don't necessarily align with our local contexts or institutional strengths. The metrics of teaching, research environment, research quality, industry engagement, and international outlook applied by THEWUR rely heavily on research that is indexed exclusively in the global database Elsevier. Research or reports published in Bangla or non-Elsevier journals don't count. Such exclusion undervalues knowledge produced in the Bangladeshi ecosystem as it compels stakeholders to opt for English-language publications and metrics-driven research.

The heavy presence of technical universities on the list suggests the bias of the ranking agency toward citation-driven calculus. Overemphasis on ranking may lead to a compromise of our fundamental educational goals. The focus should be on fostering research and teaching environments through a collaborative approach with industry and the international scene. Political considerations, unplanned institutional growth, and large class sizes throw a spanner in such efforts. On top of that, most universities don't have any ranking policy or dedicated cell to document relevant data and make them available online.

At DU, I personally witness the sluggishness of my colleagues and certain departments in updating their records. Internal politics and rivalry often lead to non-cooperation from both faculty and staff. Teachers often refrain from using their institutional digital ID to conduct research with external bodies or apply for grants from donors. This likely holds true for public universities operating under the 1973 university law. Private and technical universities exhibit a relatively high level of discipline in this regard.

Missing or misrepresented data has hurt DU. The key statistics shown on the university's website display 194,187 students. This figure includes international students of the affiliated and medical colleges of the university, but it has negatively impacted the university's score in almost all categories except for overseas students (three percent). However, DU remains resilient, with its faculties prominently featured in the subject-wise ranking. The spread shows the strength of the academic disciplines of the featured universities.

Internationalisation is one area where most of our universities suffer. DIU has claimed five percent of its students and staff are international, while at BSMAU and BAU, the figures stand at three percent and one percent, respectively. DIU has scored an impressive 65.2 for its international outlook. The universities that have done well in this sector have conducted joint research, co-authored with overseas faculty members, or arranged inbound and outbound student/faculty mobility.

Our global rankings profile acts as a health card for our higher education. We can run a series of diagnostic tests to identify the problem. Or we can simply utilise the ranking benchmarks as a template to improve upon. We can design our targeted actions backwards, taking into account the ranking criteria.

The high-performers of the region, e.g., India and Malaysia, have successfully done so by learning from global best practices and customising them to suit local needs. India, for instance, benefited from investing in STEM education while partnering with the private sector. As a result, it has 22 institutions in the global top 800 list. Conversely, Malaysia has 12 universities in the top 800 buoyed by their initiatives in internationalisation that promote joint research and faculty exchange programmes.

In our local context, we can strategically consider how smaller investments in research and teaching can yield long-term benefits. And to make our higher education sustainable, we need to render strategic support for research in disciplines that don't traditionally score high in global rankings but are crucial for national development, such as humanities and social sciences. Our universities lack a strong research culture.No wonder we scored the lowest in the research environment category. The top scorer, BUET, obtained 16.4, followed by BRACU with a score of 11.7. The issue of brain drain also influences our ranking, as many of our talented and meritorious academics leave for better opportunities abroad.

NSU and BRACU, with their policies of mandatory second degrees from abroad and PhDs as the minimum criteria for assistant professorship have encouraged Bangladeshi scholars and researchers to return home. They have supported this policy by providing competitive salaries, research grants, and institutional autonomy as incentives for academics. On the other hand, the paltry pay at public universities is far from ideal for retaining talents or cultivating a research-friendly environment. The government can learn from China, India or Pakistan, which have successfully implemented reverse brain drain initiatives. These countries have introduced policies that allow diaspora scholars to maintain their international connections while contributing to the local academic ecosystem, creating a virtuous cycle of knowledge exchange and innovation.

Bangladesh's universities, too, must tap into the expertise of their expatriate communities. To advance our global academic standing, educational lobbying can be instrumental. Using the soft power of the current government to advocate for our universities on international platforms could open new opportunities for collaboration, funding and visibility. Bangladesh's diplomatic missions also need to adopt a proactive role in promoting the country's universities, facilitating partnerships with international institutions, and attracting global talent. The local universities can create a consortium to share resources and promote local and regional research outputs, albeit in vernacular languages, as major contributions to global knowledge. The University Grants Commission (UGC) can also play a central role in creating a common platform.

Improving Bangladesh's position in global university rankings is a challenge that we must meet head-on. While backward designing strategies can assist us in aligning with ranking criteria and learning from our peers, strategic interventions like reverse brain drain and educational lobbying can provide a clear path to follow. Then again, the focus should not solely be on rankings. Our quest for global excellence needs to combine international recognition with national development.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments