The appearance and disappearance of Tagore

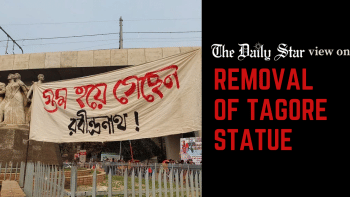

The installation and the consequent removal of a sculpture from the Dhaka University campus has triggered an interesting debate. On Tuesday, a group of students installed a large sculpture of Rabindranath Tagore next to the iconic Raju Memorial Sculpture. The campus authorities later removed the figure of a rather pensive-looking author of our national anthem, with a taped mouth, holding a nailed copy of his Gitanjali. The protesters responded by hanging a banner saying, "Tagore has been 'forcibly disappeared.'"

The left-leaning student body, Bangladesh Chhatra Union, has claimed responsibility for the installation of the protest art created by some fine arts students. The follow-up banner, with its crafty use of "disappearance," pokes at another political riddle now being investigated by different national and international agencies. The DU authorities have unwittingly opened a fresh can of worms.

The selection of Tagore and Gitanjali as an emblem of free thinking was a non-starter. The status of Tagore in Bangladesh is stronger than ever. We have universities and institutions named after him as well as national-level celebrations of his anniversaries. Gitanjali (Song of Offerings) champions love as its principal subject, with the recurrent espousal of the internal conflict between spiritual longings and earthly desires. Modelled after the medieval Indian tradition, the spiritual (i.e. apolitical) nature of the collection even helped Tagore, a British subject in colonial India, win the Nobel Prize for literature in 1913.

Tagore was deemed a problematic figure by the rulers in the erstwhile West Pakistan. Tagore's song "Aaji Bangladesher Hridoy Hotey" (From the heart of Bangladesh), among others, acted as an impetus for Bangalee nationhood in the 1940s. Those who felt Urdu and Arabic should be the building blocks for the newly partitioned country naturally felt threatened by the cultural materials available in Tagore. The Pakistani junta banned Tagore's songs in the 1960s. In response, Chhayanaut was created, and its contribution to the formation of our cultural identity is well-known.

The question then arises: do we have the same situation prevailing in Bangladesh today to forward Tagore as a symbol of freedom of expression? The answer is probably no. It is not an exaggeration to say that Tagore is more celebrated in Bangladesh today than in West Bengal. Then why tape him and pierce his work with a bleeding nail? Why didn't the protesters choose the rebel poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, whose body lies in the heart of the Dhaka University campus? Or the persecuted community of Bauls?

If you ask me, the in-your-face sculpture of Tagore placed at the entry of the ongoing Ekushey Boi Mela would have died a natural death because of its vague references. If the sculpture was intended to highlight the publisher that was initially denied entry to the fair for publishing books that challenge the official development discourse, Tagore's Gitanjali is a wrong choice. But the hasty removal of the protest art by the authorities has simply turned it into the right choice.

Dhaka University has a proud legacy of forging the consciousness and conscience of the nation. Censorship at a public university curtails our right to be exposed to and enriched by art. Dhaka University then must come up with a detailed policy of curating images and voices by the public, of the public, and for the public.

The DU authorities' action has given the sculpture its desired public attention with an added agenda of "forced disappearance." They could have simply served a 24-hour notice to the student body for vandalising public property with the unauthorised installation of a sculpture that apparently compromises the sanctity of the nearby Raju Memorial Sculpture.

Then the bigger question arises: what is the graffiti policy of Dhaka University, or any public institution, for that matter? Why are public spaces adorned with advertisements that we don't want to see? There are so many ads that promote a sense of inadequacy and insecurity in us. The depiction of perfect human figures with their perfect lives in ads constantly reminds us of our shortcomings. Isn't that an infringement of my right to be who I am? What about those graffiti that simply act as a pissing competition?

Just like artists have the right to express themselves, the university authorities also have the right to protect the beauty and sanctity of its property. But the rational thing to do was to ask the responsible parties to remove the sculpture, poster, graffiti and the like. The power of democracy lies in its ability to accommodate the voices of dissent. In a free society, every individual has the right to decide what art or entertainment they want. The Tagore sculpture could have become banal without being banned.

They say censorship is like poison gas – it can harm you once the wind shifts. Those clamping bans on the voices and views of others may be subject to their own game of censorship in the future. Freedom of expression is a two-way street. Securing freedom of expression for ourselves requires freedom of expression for others. The idea is at the core of democracy.

Dhaka University has a proud legacy of forging the consciousness and conscience of the nation. Censorship at a public university curtails our right to be exposed to and enriched by art. Dhaka University then must come up with a detailed policy of curating images and voices by the public, of the public, and for the public. While it can very well remove the graffiti presented as territorial markers, it can allow space for public art that creates public awareness. The response of the audience will tell us which art matters the most. For instance, even after the removal of the wall painting of "Shubodh has escaped," the image of a dishevelled, distraught figure with a caged sun strikes a chord with us. The word play on Shubodh (good sense or a possible proper name for a Hindu minority) stirs our imagination. A taped Tagore does not. Its placement before the Raju Memorial does not help either. But the handling of the sculpture has given it meaning that it did not originally have. Its expression was denied, proving that freedom of expression is indeed in jeopardy.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is a professor of English at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments