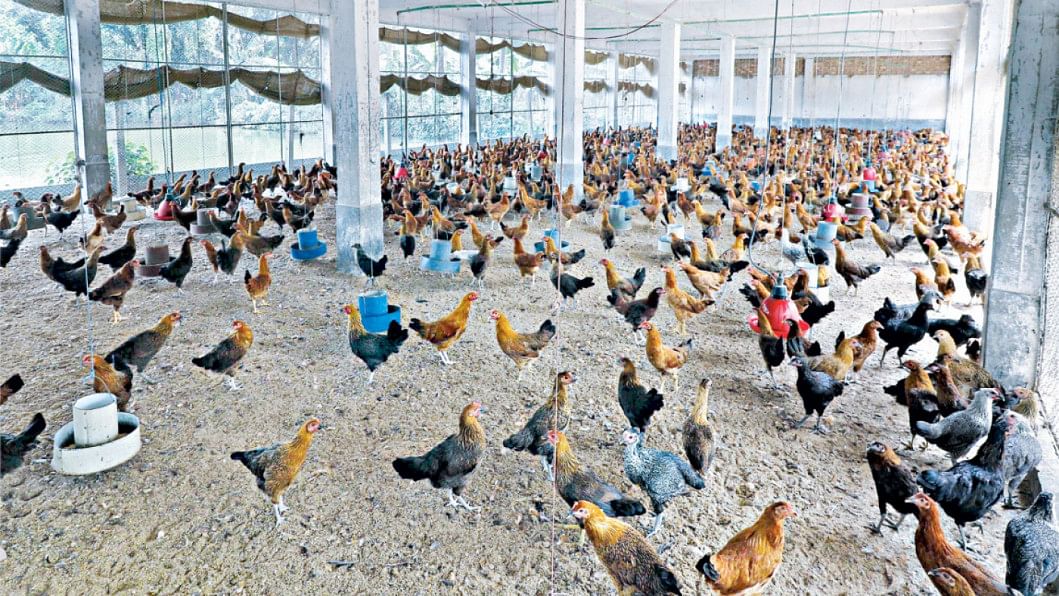

Big poultry caging small farmers

Small poultry farmers in Bangladesh are finding themselves stranded in murky waters as big players are flexing their muscle and might to shape the poultry industry, and line their pockets further. Concerns have been raised on the hegemony of big poultry farms by the Bangladesh Poultry Association (BPA), according to whom only about 60,000 to 65,000 of the 160,000 marginal poultry farmers in the country are still in business. The rest – unable to fight the big players' manipulations – were forced to pull the plug on their businesses.

It has been reported that the big players – around 12 of them – dominate the industry and manipulate the prices of chicks and poultry feed to rake in higher profits. Let's consider the prices of poultry feed, for instance. Firms that are engaged in contract farming with the big players, get to purchase 50kg sacks of poultry feed for Tk 2,500. The same is sold to marginalised/independent small poultry farmers at Tk 3,300. This is to coerce the independent, marginalised farmers into entering contract farming agreements with the large farms.

However, even for those who are in the contract farming business, there is no guarantee that their business will remain unscathed. Mahmudur Rahman Akash, a poultry farmer from Jhenaidah, is currently entangled in a Tk 50 lakh lawsuit filed by a large company. About eight months back, Akash entered into a farming contract with the company, and got 2,500 chicks to rear. He also provided a signed blank cheque to the company as guarantee when signing the contract. However, 500 of the chicks died due to disease and the company failed to deliver the much-needed medicine to Akash on time. When Akash refused to continue farming for the company, they filed a lawsuit against him.

Now the question is: did the contract – in all probability drafted by the well-paid, well equipped legal team of the big company – not contain a basic termination or severance clause, under which either of the parties could terminate an agreement by serving a 30- or 60-day notice? Why should a hapless farmer – whom the company failed to provide essential support on time – be harassed by a Tk 50 lakh lawsuit?

According to a report by this daily, around 10,000 farmers and dealers, mostly from Bogura, Joypurhat, and Jhenaidah, are facing cases related to blank cheques which are provided to big companies as guarantees. While providing bank guarantees is a standard practice in many businesses, this tool should not be used to harass and bully marginalised businesses.

Also, the farmers engaged in contract farming are paid very little by the big companies as profit. When farmers raise concerns about the selling price of poultry before signing a contract, exchange rate volatility, Ukraine-Russia-war-induced economic slowdown, cost of packaging, VAT, etc are cited as reasons for paying them the bare minimum. Unfortunately, due to a lack of supervision of this ecosystem by the government – read: the Department of Livestock Services (DLS) – there is no one to question the big companies when determining the selling price of poultry. How is the selling price of poultry even determined? Does the selling price remain volatile depending on the market? This should not be the case as it creates a new loop of exploitation of farmers by the big companies.

According to a report by this daily, around 10,000 farmers and dealers, mostly from Bogura, Joypurhat, and Jhenaidah, are facing cases related to blank cheques which are provided to big companies as guarantees. While providing bank guarantees is a standard practice in many businesses, this tool should not be used to harass and bully marginalised businesses.

Moreover, the free rein of these companies to manipulate the market through price syndication also creates additional pressure on consumers, who have to pay a premium to buy poultry protein. Between January and March this year, poultry prices kept spiralling, going beyond the purchasing capacity of the common people, with broiler chickens being sold at a whopping Tk 280 per kg in the kitchen markets.

Eventually, the Directorate of National Consumer Rights Protection had to intervene and sit with the four major producers to bring down the prices in the wholesale market. The readiness with which these companies agreed to bring down the prices by Tk 30-40 per kg indicates that they have been making a profit much higher than this. Businesses would never take a loss just to serve the people.

Interestingly, citing this same timeframe, Bangladesh Poultry Association alleged that big poultry farms made an extra profit of Tk 936 crore through syndication. According to them, the big players made a 40 percent margin, selling poultry at Tk 230-240 per kg, while the production cost was only around Tk 130-140 per kg.

While transformation in the poultry sector is a welcome move, small, independent, marginalised farmers and those involved in contract farming with big companies need legal resources and logistics-related protection from authorities and policymakers. The National Poultry Development Policy, 2008 (NPDP) stipulates that proper technical assistance should be provided to marginal and poor farmers so that they can earn through poultry farming. The NPDP has entrusted the DLS with the responsibility to monitor poultry markets, remove discrepancies and anomalies, curb the influence of dealers, and protect marginalised farmers. Unfortunately, the DLS seems to have failed in all of these responsibilities, and the number of poultry farmers plummets while poultry prices skyrocket in the markets.

In the outgoing budget, the government cut down tariffs on the import of poultry feed. Despite that, imported feed is becoming expensive. As such, the government should subsidise it and reduce the import duty further to support the industry.

Poultry farming has immense potential in Bangladesh, given that around 90 percent of rural Bangladeshi households keep poultry. But challenges remain in fully leveraging this opportunity and enabling small households to become self-sufficient small farmers. The decreasing number of poultry farms raise fears that there might be a shortfall in the supply of poultry in the market, pushing the prices up further. The price hike of eggs has already been attributed to the closing down of farms.

It is high time for the government to take a closer look at the malpractices that are forcing farmers out of the poultry business, and take immediate measures to create a level playing field for all in the industry.

Tasneem Tayeb is a columnist for The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is @tasneem_tayeb

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments