89th Birthday of Serajul Islam Choudhury: Bangladesh’s premier public intellectual

Today marks the 89th birthday of Serajul Islam Choudhury. At a conjuncture characterised by the constitutive contradictions and crises of such systems of exploitation and oppression as capitalism and imperialism, Serajul Islam's Choudhury's work continues to speak to the emancipatory struggles of the oppressed around the country, and even the world.

Literary and cultural critic, social and political analyst, media commentator, teacher, pedagogist, translator, editor, columnist, activist, and surely an outstanding teacher of English literature—Choudhury continues to be one of the most prolific writers in the Bangla language today. And it is no less significant that, even at 88, he recently led the Palestinian Solidarity rally in Dhaka, attesting to his characteristic activism that variously informs his written work.

Serajul Islam Choudhury is the author of more than a hundred books and numerous essays. He has also written several books in English, including some ground-breaking ones on the revolutionary Bangalee poet Kazi Nazrul Islam—Choudhury's all-time favourite. But, more than anything else, Serajul Islam Choudhury is a major and leading intellectual of our time, committed as he is to nothing short of the total emancipation of humanity in its entirety.

I cannot do justice to the entire range of Choudhury's massive work in this short piece. But I intend to touch on the significance of certain aspects of his work. To begin with, Choudhury's work remains organically responsive to and thoroughly informed by our own national liberation movement, class struggles, and other forms of struggle in Bangladesh. One who always historicises his own people's conditions of being and becoming, Choudhury continues to make interventions in such broad areas as society, politics, political economy, culture, and history, while making the points that telling without doing is profoundly insufficient and that gnosis (knowledge) without praxis (practice informed by knowledge) is simply empty.

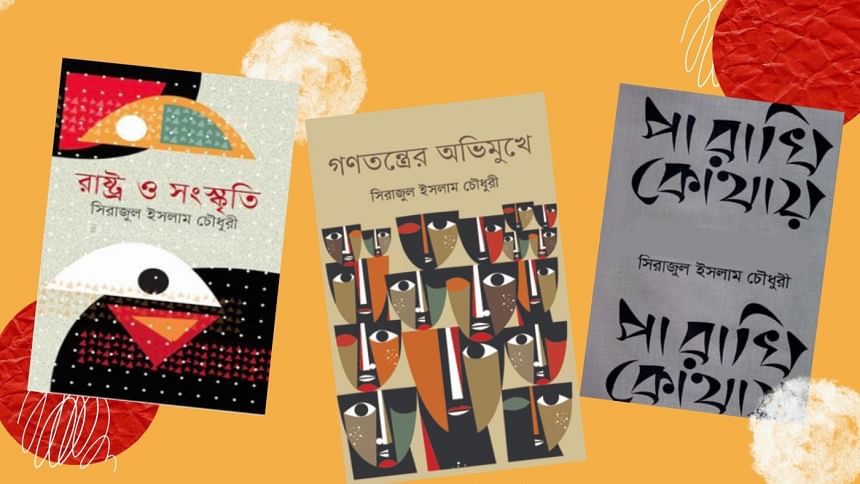

Indeed, for about six decades now, Choudhury has been making an inventory of the daily acts of people's resistance and modes of forbearance and survival as well as their aspirations and hopes, exemplified in a range of his works from, say, his earlier book Nirasroy Greehi (1978) and Bangalee Kake Boli (1988), to Swadhinota Spriha Sammyer Bhoy (1988) and Gonotontrer Pokkho-Bipokkho (1991), to Rashtro o Sankskriti (1993) and Rashtrer Malikana (1997), to Bicchinnotay Osommoti (2014) and Pa Raakhi Kothay (2018), to Vidyasagar o Koyekti Prosongo (2021), among many others. One would also do well to cite yet another example. Choudhury used to write an immensely popular—if not populist—column called "Somoy Bahiya Jay" with commendable verve and unflagging enthusiasm in a style that is distinctively Choudhuryian. He has exemplarily evolved a prose-style that makes his work pleasantly readable and accessible. For him, this very question of style is not only an aesthetic question but also a political one.

Choudhury, consistently critical of individualism and opportunist liberalism, centres the struggles of ordinary people in his work, supports their movements, and writes extensively about them, exemplifying the role of a public intellectual in Bangladesh. Contesting corporations and politicians who invoke "people" to abuse them, Choudhury addresses real material contradictions and issues of class, gender, race, and nationality. His critiques of liberal humanism are evident in his incisive analyses of figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and E M Forster, just to provide two quick examples.

And, in opposition to the tradition named above, Choudhury clearly identifies the people for whom he tirelessly writes and fights. The people for him, then, are clearly the majority in the country—the toiling masses—peasants and workers, including women as well as ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities, ignored and oppressed as they are. And he writes about them from the perspectives of their collective emancipation. To put it bluntly: human emancipation itself constitutes the most fundamental, abiding theme in Choudhury's work. In fact, the question of people's emancipation remains organic and integral to the entire constellation of Choudhury's interrogations and interventions from his early works to one of his major works called Jatiyotabad, Samprodayikota o Jonogoner Mukti (2015), which can justly be regarded as his historiographical tour de force.

Let me now briefly describe one of the predominant approaches used in Choudhury's work. Indeed, what—among other things—enables his interventions to remain attentive to both connectedness and contradictions as well as to the "specific" in its historical determinateness is dialectics itself. Dialectics is Choudhury's weapon. For him, dialectics—as a science of the general laws of contradiction, motion, and transformation—is not merely a scholarly or academic exercise; it is a radical tool. He sharpens and deploys the weapon of dialectics in his writing. In fact, it enables him not only to zero in on the specific or the particular as such, prompting him to advance a concrete analysis of a concrete situation, but also to discern and demystify both contradictions and connections between the specific and the general, between the particular and the universal, between the abstract and the concrete, between critique and action, between gnosis and praxis. But only discerning or demystifying contradictions and connections is never enough for Serajul Islam Choudhury. He identifies them in the interest of social transformation and emancipation, broadly speaking.

Further, in the Marxist tradition, Choudhury's approach reckons the class struggle as both the horizon and motor of world history. This approach enables us to see how the development of the productive forces brings into existence different production relations and different forms of class society. And this approach is also nothing short of a revolutionary one that makes us see how the question of the entirety of human emancipation remains connected to the transvaluation of the questions of property relations, the social division of labour, and the process of social reproduction, and so on—i.e., connected to the total abolition of value (exchange value) itself—"an abolition that can be effected only by a revolution," as Marx and Engels put it in The Communist Manifesto.

As the German Marxist theorist Walter Benjamin points out in his classic work On the Concept of History: Class struggle, which for a historian schooled in Marx is always in evidence, is a fight for the crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual things could exist. Choudhury's approach demystifies how the class struggle in its concrete historical-becoming is a fight for "the crude and material things" as much as it is a struggle for the "refined and spiritual things," interconnected as they are. Thus, his approach considers both political economy and culture as the dialectically interconnected sites of life-and-death struggles of the oppressed.

Serajul Islam Choudhury explores the role of intellectuals in his essay Buddhijibeeder Kajkormo o Daydayitto. While intellectuals like Antonio Gramsci, Noam Chomsky, and Edward Said—their different styles and approaches notwithstanding—accentuate the oppositional role of intellectuals committed to radical change, Choudhury supports a similar stance. He believes an intellectual must question oppressive systems and speak truth to power for revolutionary social transformation. Choudhury also stresses the importance of reaching others with these critical ideas, as collective effort is essential for change.

Choudhury's views on the role of intellectuals apply to himself, as he clearly identifies systems of oppression such as capitalism, imperialism, communalism, and patriarchy. He is recognised as Bangladesh's leading anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, anti-colonial, anti-communal, and anti-patriarchal public intellectual. Beyond opposing these systems, Choudhury advocates for socialism, arguing there are no contradictions between socialism and democracy; rather, to be socialist is to be democratic.

A public intellectual as he is, Choudhury in his work touches upon almost every aspect of the life of the masses in Bangladesh. To the extent that he does it, he is bound to cross—and range across—disciplinary borders and boundaries, as he surely does in his work. This is why Choudhury is equally comfortable with producing literary and cultural criticism, political commentary, editorial essay, autobiographical narrative, tract and treatise, newspaper column, and so on, in which the linguistic, the literary, the social, the political, the historical, and the cultural interpenetrate and intersect, exemplifying a radical interdisciplinarity.

For instance, Choudhury has written on Tolstoy and on such modernists as Conrad, Forster, Lawrence, Joyce, Yeats, Pound, and Eliot, among others. Of course, Choudhury has written on every major, canonical Bangalee writer—Madhusudan Dutta, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Rabindranath Tagore, Mir Mosharrof Hossain, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Manik Bandyopadhyay, Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Jibanananda Das, and Syed Waliullah. The list here is by no means exhaustive. Choudhury has produced a remarkable body of work that traverses a wide range of concerns directly relevant to the contemporary life of the suffering masses in Bangladesh. And it is in this body of work that Choudhury most exemplarily forges organic links among the political, the social, the historical, and the cultural all at once. Moreover, it is in that body of work that Choudhury has consistently advanced and relayed his formulation—one that appears fundamentally Gramscian to me—that there is no alternative to forging links between the intellectuals and the masses, if "the point is to change the world," to quote Marx's eleventh thesis on Feuerbach.

I have hitherto selectively drawn on Choudhury's range of works to underline a few of his historically significant and still relevant contributions. An outstanding critic and perceptive analyst, Choudhury teaches that producing knowledge is necessary but not sufficient. He emphasises that knowledge must be used for social change and the emancipation of the masses. Firmly committed to the Marxian principle of praxis, Choudhury values knowledge that transcends mere interpretation, aiming to transform people's consciousness.

As his former student and a member of the editorial board of his national weekly Somoy, I have learned immensely from Serajul Islam Choudhury. His work taught me that teachers, intellectuals, and educators must fulfil their social and political responsibilities and remain accountable for the knowledge they produce. On his 89th birthday, we owe Choudhury immense gratitude for his contributions to our country and even the world.

Dr Azfar Hussain is currently Summer Distinguished Professor of English & Humanities at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB). He is director of the graduate programme in social innovation and a professor of interdisciplinary studies at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, US. He is also the vice-president of the US-based Global Center for Advanced Studies (GCAS).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments