Are 'open spaces' really open?

Open spaces are an integral part of an ideal living environment. According to the Dhaka Metropolitan Development Plan (DMDP), any portion of a zoning plot that is essentially free of structures and serves the purpose of visual relief and buffering from buildings and structural mass is known as an open space. And with the gradual increase in population and rapid urbanisation, the number of open spaces in our megacity is drastically decreasing.

To combat this, Dhaka South City Corporation (DSCC) has taken up the Jol-Sobujer Dhaka Project. Parks and playgrounds have been refurbished under the Dhaka North City Corporation's Green Dhaka Campaign as well. Certain publications have mentioned how the design decisions were taken by prioritising the opinions of different users' groups. But the question is: who is defined as a user group here, and by whom?

Take for example the reformation of Justice Shahabuddin Park. One of its prominent features is a fenced wall that controls access to the park via two gates, along with guards. There is a restriction of entrance for hawkers and beggars. For those who have grown up munching on peanuts while taking a stroll in a park, this activity now becoming an established restriction in the name of security can be rather questionable.

Every element of the built environment has psychological effects and we, as users, seek connection with them for comfort.

As celebrated Iranian-British architect Zaha Hadid puts it, "Architecture should be able to excite you, calm you, and make you think, do the spaces around you have a conversation with you, or do you enter a space, and it affects your mood."

Unfortunately, most contemporary design elements in our country's architectural practice are replicated directly from the West, with little thought put into its context/background, and its psychological effect. We forget that architecture, with its powerful abilities, can sometimes exclude. And claims that people's opinions are being included in decision-making with regard to open spaces is certainly debatable.

The field of Banani Chairman Bari, which was left abandoned for years and lacked proper security and accessibility, is another example. After its reformation, the local community has been revived and all sorts of events are now held there. The park is monitored by security guards and access to it is controlled using two gates. However, the same provision that is ensuring security is also misusing it. The security guard and the maintenance team is seen keeping only one gate open most of the time, that too in a way which makes it difficult for a new visitor to find it. Also, visitors belonging to the nearby informal settlement routinely receive stares, and are made to feel out of place and uncomfortable. Such practices in public spaces continue to stigmatise and exclude certain social classes.

Recent renovation projects have also led to abandoned fields being replaced with artificial turf to accommodate different sports and related competitions. However, this has made their maintenance a little expensive, and many powerful local clubs are exploiting this, and at times appropriating the facilities for themselves only. This has made other community members question the motives behind the fields' renovation. When a piece of public land can be locked away from a community, it represents the disparities in our democracy, and implies a poor sense of community bonding and ownership.

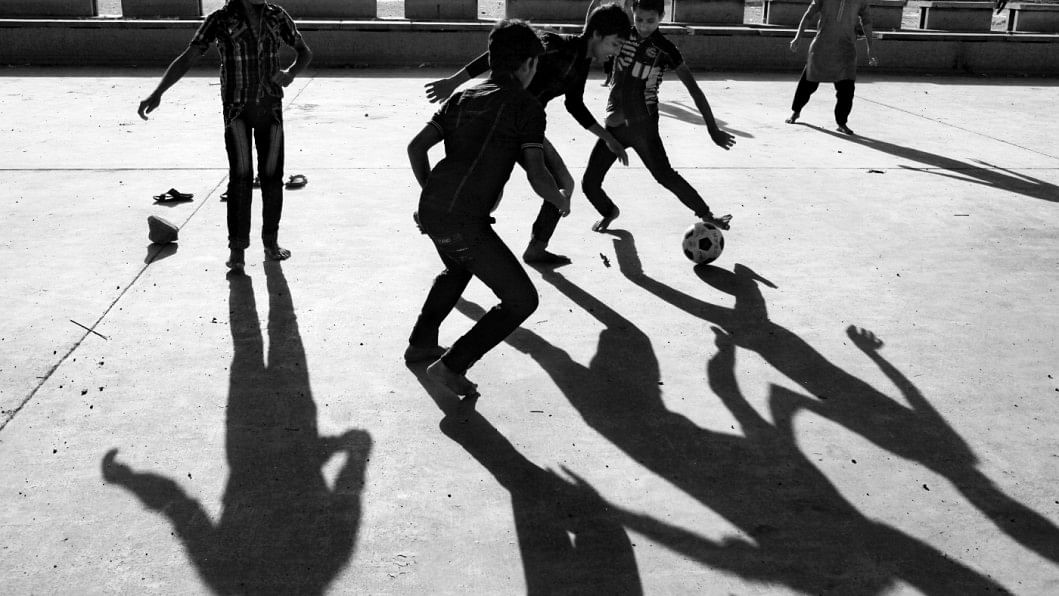

On the other hand, many open spaces, even after going through such transformation and security control, still see plenty of malpractices such as drug use, takeovers by local goons, etc. As a result, people are forced to avoid the only open spaces in their neighbourhood. Children are seen playing on the roadside and not using park spaces.

Our built environment is a negotiation between humans and non-humans. The openness of a place doesn't only comfort users visually, but psychologically as well. As professionals, we should have a vision for a good placemaking approach – where a comfortable relationship is established between the place, its visitors and their activities – rather than just following design trends insensitively. While city corporations taking the aforementioned initiatives to make a "place" out of abundant land is a positive step towards a better living environment, the willingness to adapt and change is what can lead to them being successful.

Every area has its community, culture, and ability to make a place out of its surrounding. Rather than just trying to beautify a piece of land and keeping it as a piece of artwork, the initiative should be to create more people-centred spaces. In the bigger picture, if the usability of the place is not as significant as its financial expense, it will be a waste of the valuable wealth of the country and its people.

Rafiah Binte Noman is a graduate from the department of architecture at Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments