With automatic pricing formula, BPC can't cry wolf about losses

Until very recently, the prices of liquid fuels such as diesel, octane, petrol and kerosene were fixed administratively by the government. There were always misgivings among the general public that the government is arbitrarily fixing the prices. Even though there was a formula of sorts, it was never revealed to the public. What transpired was that the administratively set prices for a long period were in favour of Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC), the state-run company that imports, distributes and markets oil. During this period, the international crude oil price was very low, so the BPC made a hefty profit. Consumers felt they were being deprived of the benefits of low oil prices.

For a long, long time, the pricing principle was that diesel, being a common person's fuel, must be subsidised, while petrol/octane, being a rich person's fuel, must be taxed. As a result, for a long time, diesel was much cheaper than petrol. The BPC used this cross-subsidy to manage its books. The problem started when compressed natural gas (CNG) was introduced and thousands of vehicles moved away from petrol. Moreover, the low price of diesel prompted consumers to opt for diesel vehicles. The cross-subsidy was no longer working for BPC as demand for petrol started to fall and the consumption of diesel started to increase at a rapid pace.

The situation became untenable for the BPC when oil prices skyrocketed as a result of the Ukraine-Russia war. The financial burden became so heavy that huge subsidies had to be provided by the government to balance BPC's books. The government finally decided that it would no longer subsidise diesel, so the diesel price was increased from Tk 80 to Tk 110. This had an immediate negative impact on economic activities. Consumer prices of foodstuff shot up, leading to an inflation rate of over nine percent that hasn't come down.

Soon after the massive diesel price hike, the global oil price started to fall, but the government did not bother to reduce the domestic oil price. When consumers started clamouring for a reduction in energy prices, it responded by a nominal reduction, which angered the public further. The government understood it had to do something, and after much dilly-dallying, it introduced the so-called "automatic pricing formula" for petroleum products in March this year.

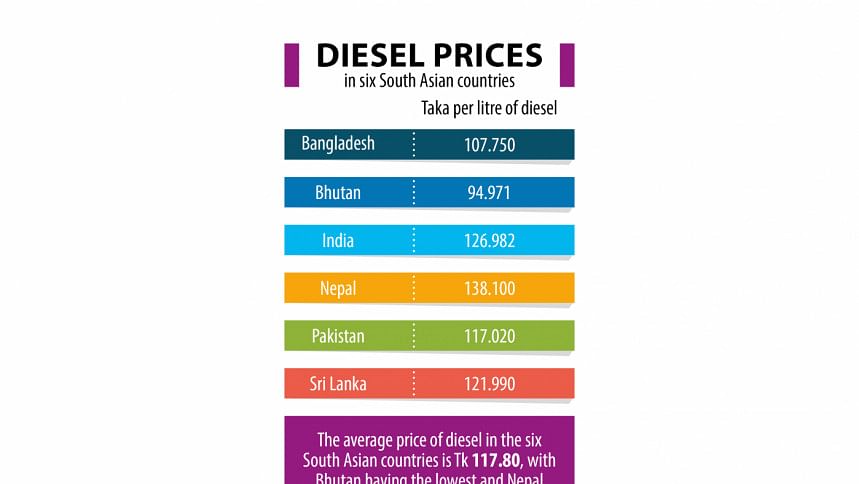

A comparison of diesel prices in six South Asian countries—Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka—reveals that Bangladesh has the second cheapest diesel price (Bhutan has the cheapest). However, a nearly Tk 108/litre price is a break from the old philosophy that diesel, the most important liquid fuel for developing countries, needs to be subsidised to foster the country's economic growth. India introduced the market-based pricing mechanism a long time back. Diesel price in India is high because of two taxes imposed on it: first, the federal government's excise duty, and second, the state government's VAT.

Whether diesel should be taxed or subsidised is a contentious issue. Some economists believe that since it is imported, it should not be subsidised, while another group believes it should be subsidised especially for irrigation. After the initiation of automatic pricing, diesel has become a taxed product, the impact of which has already been felt with rising inflation. The argument often furthered by the energy ministry in support of keeping the diesel price high is to prevent smuggling to India. At one time, the price differential was so high that a substantial quantity of diesel got smuggled to India. With the new automatically set price, the differential is not high enough to encourage smuggling, given the associated risks and costs involved.

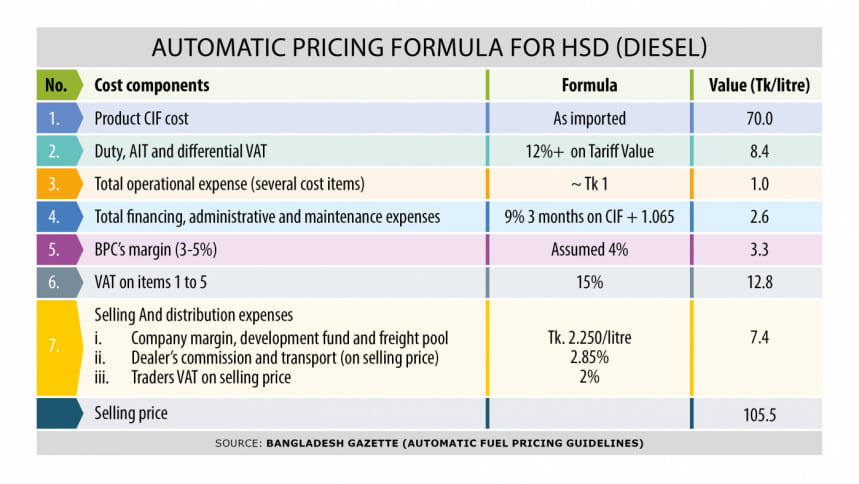

To understand the full implications of the automatic pricing formula, let's look at the main cost components that make up the selling price of imported diesel. In the actual formula, there is a 14 percent contribution from ERL that slightly lowers the selling price. Since this exercise is only for illustrating the main cost components, to keep the formula simple, that is neglected. Also neglected are other miscellaneous small cost components that have very little impact on the final total selling price. For this case study, the CIF tariff is assumed to be Tk 70/litre. As can be seen, the price at the refuelling pump is nearly 50 percent more than the imported product price. Of course, in this there are some essential items such as the distribution company's carrying cost and the dealer's commission, but also there are many other costs that give the BPC a fairly good profit. Moreover, the government also makes a healthy revenue collection from diesel sales: more than Tk 20/litre on a selling price of Tk 106/litre. In principle, there is nothing wrong with this because many countries impose taxes and duties on imported petroleum products. European countries heavily tax diesel and gasoline. However, this deviates from the long-standing practice of subsidising diesel, which is used for irrigation and transport of foodstuff to the cities from rural areas.

BPC has a tendency to show that it is incurring losses and often claims that it needs funds for development projects. The company has undertaken several such projects, of which the second refinery is the biggest. Among the significant projects undertaken by the BPC in the recent past are: i) a second refinery; ii) Bangladesh-India friendship pipeline to carry diesel; iii) Parbatipur-Siliguri transboundary pipeline; iv) a 238km pipeline from Chattogram to Godnile, Narayanganj with an extension to Fatullah (8.29km), and Cumilla to Chandpur (59.23km) for diesel; v) a 17km pipeline for jet fuel from Pitalganj to Kurmitola; vi) 110km onshore and offshore pipeline under single-point mooring (SPM) system for imported crude and refined petroleum oils from carrying vessels to ERL storage; and vii) a smart fuel distribution monitoring system (SFDMS) to modernise and streamline the fuel distribution process.

It is customary for the government to provide funding as loans, which the BPC has to pay back. Therefore, in the annual accounting, debt servicing will show up as an expense. These projects are justified with the reason that they would help the BPC manage its operations better and thus save money, or at least the costs would be fully recovered. There are, however, situations where these projects are inordinately delayed or face bottlenecks; the second refinery is a case in point. In such cases, the investment cost becomes a burden for the BPC.

Another oft-raised issue is the subsidy provided to the BPC when diesel was sold at a price lower than the international price. It is important to note that if a subsidy has been provided, there is no justification for that expense to be shown in the BPC's books as an outstanding amount.

Following the introduction of the new pricing formula for petroleum products, there is no way that the BPC can lose money, because it is a cost-plus formula. The imported costs of petroleum products as well as the cost of delivery borne by the distribution companies as well as the BPC's financing and operation costs are all fully recovered. On top of that, there is the BPC's margin, which should cover development costs.

Dr Ijaz Hossain is former dean of engineering at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments