Is Bangladesh’s ‘nuclear prestige’ an illusion?

It came as an unexpected surprise in early April when Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina asked Rosatom, the Russian state corporation that specialises in nuclear energy, to consider building another nuclear power station in Rooppur. The revelation came at a time when Bangladesh has already been struggling with depleting foreign exchange reserves, high inflation, load-shedding, poor human development, and an increasing debt burden. The country has already begun to seek new loans to repay its existing ones, as per a recent CPD analysis. In addition, Bangladesh is also taking fresh loans at high interest rates to buy oil and LNG from foreign sources. The country finds itself in an exceedingly precarious situation as both its external borrowings and debt-servicing obligations are increasing at a rapid pace. There is also uncertainty over securing a fresh source of foreign currency inflow to cover future debt.

In this circumstance, does Bangladesh really require another nuclear power plant? Or is the decision partly motivated by the pursuit of prestige?

"Nuclear prestige" refers to the high status that governments believe they can acquire by building nuclear weapons. Countries armed with nuclear weapons perceive it as a symbol of prestige because it represents the exclusive ability of employing an advanced technology, and the image of leadership it projects to the international community.

Research has shown that at key historical junctures, countries pursued nuclear weapons to gain prestige. Harvard political scientist Alastair Iain Johnston's research in 1995 showed that Mao's decision to construct a nuclear bomb was motivated in part by a desire to gain international prominence. American foreign policy and intelligence executive Gregory F Treverton used in his book, Framing Compellent Strategies, the example of Chandrasekhara Rao, whose reason for India's first explosion in 1974 was that nuclear weapons would enhance the country's prestige. Similar observations were made about France's Charles De Gaulle by Princeton academic Wilfried Kohl in 1971, and by Yale professor Barry O'Neill in 2006 about Iraq's Saddam Hussein pondering the use of nuclear weapons to acquire prestige and regional leadership.

Only 32 of the world's 195 countries have nuclear power facilities. With the exception of two lower middle-income countries, Pakistan and India, the majority of these nations belong to the high- or higher-middle-income category. These two nations' plans to build nuclear power facilities went hand in hand with their strategy to increase their nuclear weapons capabilities. India's nuclear programme began in the mid-1940s, when then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru envisioned the potential to cover the complete fuel cycle, and India purchased its first reactor from Canada in the 1950s.

Similarly, China's nuclear programme was established in 1955, led by Mao Zedong. Ultimately, Pakistan took a significant step towards nuclear armament under the guidance of Bhutto following the loss of East Pakistan in 1971. These countries exhibited a common pattern of nuclear adoption. They developed their nuclear weapon programmes due to concerns about national security and the need to assert their national identity in a tense geopolitical landscape. The potential of conflict drove these nations to construct and solidify their national and military identities.

Interestingly, when Bangladesh decided to construct a nuclear power plant, certain interest groups portrayed it as a symbol of prestige. What they overlooked is that the historical concept of prestige is associated with gaining technical competence to produce weapons and energy, rather than importing nuclear technology and expertise from overseas and remaining indefinitely dependent on external power. The nuclear collaboration between Bangladesh and Russia is not a reflection of Bangladesh's financial capabilities, nor does it demonstrate its technical capacity to develop nuclear power plants on its own using domestic technology.

Russia is providing 90 percent of the funds in the form of loans. In other words, Russia is bankrolling this project so that Bangladesh can purchase Russian nuclear equipment and employ Russian consultants, specialists, and personnel. This so-called financial capacity, in reality, is a future debt burden for our citizens. And then, once the nuclear power plant is built, Russia will operate it as long as Bangladesh does not develop the capacity to run the project itself. Furthermore, the tripartite agreement between Bangladesh, Russia, and India enabled India to develop Bangladesh's human resource capacity for Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant (RNPP). It is reasonable if India is proud of its human resource development efforts in Bangladesh. But is it a matter of prestige for Bangladesh to receive human resource training from India?

This leads us to the questions that are central to this discussion. Is this nuclear prestige false? Who benefits from this constructed sense of prestige?

Megaprojects are commonly recognised as effective means to demonstrate modernity and development. In numerous developing nations, dominant political parties frequently employ large-scale projects as a strategy to push the prominence of development, despite the fact that the benefits derived from these projects hardly ever reach the people.

For a weak state, lacking the ability to manage inflation, guarantee public service provision, and enforce laws, it is easier to create a false impression of progress than to allow the citizens to reap the benefits of true development. Building a nuclear power plant gave politicians a chance to create an illusion of attaining technical prowess when, in reality, we are simply boasting about the abilities and expertise of others.

It is noteworthy that around one-third of countries with nuclear power plants produce less than 10 percent of their total electricity from nuclear energy. These countries include Japan, Germany, China, Brazil, South Africa, Argentina, Mexico, Netherlands, Iran, and India. If nuclear power is such an efficient and ecologically beneficial energy source, why aren't these countries building more nuclear power plants?

The answer is straightforward. Even nations with sophisticated capabilities refrain from relying on nuclear power due to the inherent risks, exorbitant costs, and the long-lasting damage caused by radioactive waste for thousands of years. Despite India's nuclear weapons capacity, why was the contribution of nuclear power in its energy generation only 3.1 percent by 2022, as reported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)? Once the RNPP commences operation, the share of nuclear power in Bangladesh's electricity output will be approximately seven percent, subject to future capacity increases. Constructing a second one will further increase the share.

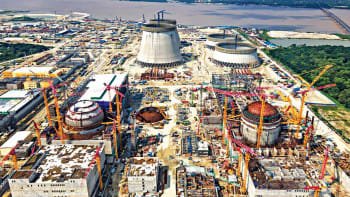

Bangladesh has already borrowed $11.38 billion from Russia to build the first 2,400MW RNPP. The 20-year repayment period will begin in 2027, with $500 million per year for the first three years and then less in subsequent years. The first and second units were originally planned to be finished in 2023 and 2024, respectively. However, so far, 85 percent of the construction has been completed, with a revised completion date set for 2026.

How can a country consider building a second nuclear power plant when it doesn't know whether the first one will be able to operate successfully? We are not sure whether it will take two to three years or more for Bangladesh to be fully capable of operating RNPP on its own. With all of these uncertainties and risks, how can a country risk another one?

Since the days of Mao Zedong and Jawaharlal Nehru, the world has seen significant transformation. In the international arena, prestige is now defined as the ability to invest in research and development to exploit cutting-edge solar, wind, and green hydrogen technologies. Ironically, Bangladesh continues to adhere to a misleading definition of nuclear prestige. The country needs to realise its true potential, rather than relying on the illusion of nuclear prestige.

Moshahida Sultana Ritu is associate professor at the Department of Accounting and Information Systems of the University of Dhaka.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments