Can Bangladesh be the next ‘breakout nation’?

In his 2012 classic, Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles, Ruchir Sharma outlined his process of forecasting which nations would thrive and which would falter in a world reshaped by slower growth. Of 200 emerging economies globally only 56 nations have ever reached "developed" status. Why do some emerging nations successfully "breakout?" And why do others stay developing for decades? Sharma found 10 relevant factors across political, economic, and financial verticals. And based on this, a positive era in Bangladesh might be materialising.

Eight weeks into the Prof Yunus-led 17-person interim government, Bangladesh is on the right track. The appointments have been strong and inclusive: four women, two minorities, two students, one Islamic scholar—all respected, and spearheaded by a respected Nobel laureate. These choices have brought instant credibility to the transitional government, both at home and abroad.

The previous regime died in broadband darkness, with the internet now revived. Tech-savvy Gen Z, angered over the toxic political climate and issues of inequality are finally represented. People are back to work. Law and order has been restored (even though there is some work left), and the nation has not fallen prey to religious fundamentalism with retributive violence contained. The first steps with our second liberation for democracy are cautiously progressing.

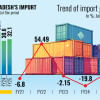

The interim government's first priorities make sense: restoration of security, full investigation of all crimes, reestablishment of the rule of law, structural reforms, and a smooth transition to democratic representation. The good news is our economy is resilient and civil society robust. Bangladesh has become the second-largest garment exporter in the world, after China. These factories employ more than four million workers, many of them young women, often the first in their families to have a salaried job. Working age demographics are incredibly strong. Per capita income has tripled in the last decade with over 25 million people lifted out of poverty in the past 20 years.

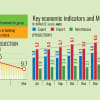

However, Bangladesh was damaged under the growing weight of cronyism: the capital markets and banking system are weak, the wealthiest 10 percent of the population control 41 percent of the nation's income, while the bottom 10 percent just 1.3 percent. Two-fifths of our young people lack regular employment. Since 2020, 10 percent inflation has undermined stability with the country's foreign reserves falling. While unnerving, remedies are available, particularly with Dr Ahsan H Mansur, leading the charge as Bangladesh Bank Governor and Dr Salehuddin Ahmed as adviser for finance and planning to the interim government. Together, they are Bangladesh's economic dream-team.

So, what is one of the top economic priorities for the country? Clearly, it is foreign investments. How do you achieve success in attracting FDI? First, by recognising the issue and second by understanding how the pillars of investments work. Political, economic, and financial markets are not discreet verticals. The interim government needs to know how international investors think. Money goes to the least troubled areas. And, as mundane and oversimplified these terms may sound, transparency and rule of law are the foundations of a virtuous FDI cycle. An investor who understands the risk and reward of their investment will decide for himself which risk is worth taking. Legal protection of that capital is a must and trusting the courts to administer the rules around that investment is compulsory. Every market, and Bangladesh is no different, competes for global capital. No policymaker can forget that. No country lives in a financial market vacuum with a war chest of investment dollars pointed in their direction. Life just doesn't work like that.

Sharma noted, "There is a rough sweet spot for investment in emerging markets. Looking at my list of the 56 successful postwar economies in which growth exceeded six percent for decades, on average these countries were investing about 25 percent of GDP during the boom years."

The interim government must recognise, as I am sure Prof Yunus does, that unlike the political and economic verticals which are inwardly focused, the financial market vertical is external facing. Investor support from foreign institutions, sovereign wealth funds, and private sector FDI are critical. Capital markets, debt and equity are crucial elements of finance. If capital markets don't work, most likely the rest of the economy is not working. A dedicated person liaising with foreign investors is a crucial resource. This is my core message.

For global investors, Bangladesh is an easier country to navigate compared to others in the region: one language, mostly one ethnicity, and high levels of communal harmony (there have been reports of issues and those must be dealt with lawfully) makes it a good destination for FDI. What the country and this new administration must do is understand what drives investment decisions and put a framework in place to reflect that understanding. It is not rocket science, but simple thoughtfulness about investment decision mindset. If done properly, Bangladesh can be and will be another "breakout nation"—hopefully the 57th economy in Sharma's next book update.

Tanvir Ghani is president of an investment firm in Hong Kong and San Francisco and a former managing director at Goldman Sachs.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments