Can Dr Yunus’s vision for youth leadership deliver change?

Yesterday, I was listening to our chief adviser, Dr Muhammad Yunus, during an interview on Voice of America (VoA). At one point, Dr Yunus made a compelling point while responding to VoA broadcast journalist Anis Ahmed. He said we should entrust leadership to our youth, allowing them to shape the future of a new Bangladesh. He envisions a brighter, more inclusive, and discrimination-free Bangladesh—one built by the youth themselves, a vision ignited by the July 2024 movement that led to the ousting of Sheikh Hasina's regime.

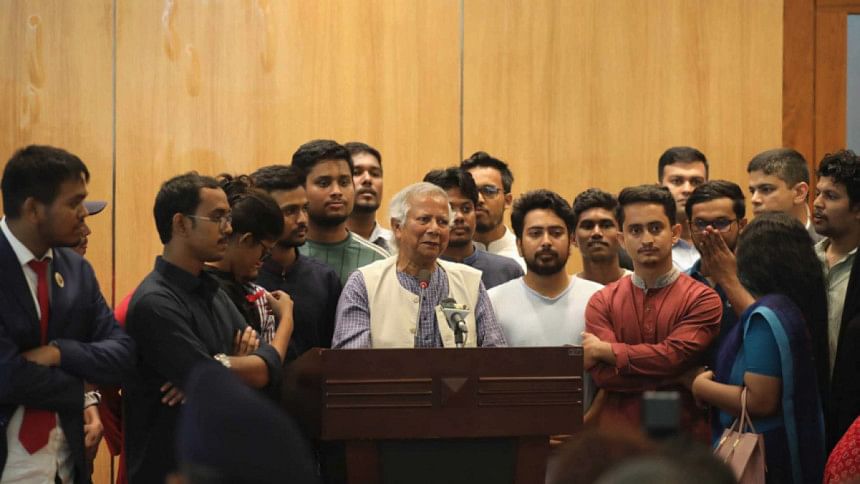

In his first address to the nation after the mass uprising, Dr Yunus declared that students were the primary force behind his interim government. Later, at a US conference, he introduced one of his special assistants as the mastermind of the August 5, 2024, movement. Although led by students, the movement garnered support from people from all walks of life—private university students, rickshaw pullers, workers, private-sector employees, businesspeople, and others. They could no longer endure the repression, corruption, and abuse of power that had plagued the country for more than 15 years. Rising kitchen market prices, a failing banking sector, bureaucratic corruption, and the politicisation of government institutions had driven the people to the brink. It was the students' movement that sparked the nation's call for change.

However, this raises an important question about the definition of "youth" that Dr Yunus refers to. Are these youths merely students, still dependent on their parents and lacking real-world experience? What age group is he talking about?

In reality, except for two student advisers in the interim government, the rest are older individuals. People are questioning their ability to manage the country effectively, as two months have passed, and many of these officials have struggled to handle their respective secretariats. The interim government is overwhelmingly dominated by former bureaucrats, NGO members, and Grameen Bank officials, with little representation from the private sector, labourers, or industries that generate employment for the youth and drive the economy.

Consider the readymade garments (RMG) sector, the largest employment generator and a key contributor to import and export revenue, alongside remittances from expatriate workers that help stabilise foreign reserves and control the exchange rate. Yet, there is no representation from this sector in the interim government, and no dialogue with its stakeholders has been initiated. Meanwhile, law and order has deteriorated, critically affecting both the RMG and pharmaceutical industries. Many factory workers and officials haven't received salaries for months. These employees are often the sole breadwinners for their families, responsible for rent, bills, and their children's education. Is the government aware of how these families are managing under these circumstances?

The prices of essential commodities had already skyrocketed under Sheikh Hasina's government, which blamed business syndicates for the crisis. It's now believed those syndicates were backed by the regime to serve their own corrupt interests. But what is this interim government's excuse? Why did the price of eggs, a staple source of protein, soar to Tk 170 per dozen? The mobile courts run by the Consumer Rights Authority have become little more than a media spectacle, with no tangible impact on the market.

The interim government should conduct a survey among Dhaka's middle- and lower-middle classes to evaluate its performance over the past two months. These people, enduring daily hardships with a dysfunctional traffic system and law-and-order failures, are the parents, siblings, and relatives of the very students Dr Yunus has tasked with leading the nation. Though they remain quiet for now, their grievances are growing, and no one knows when they might become too much.

Let's return to the core issue: the "youth." In my view, youth should not be limited to students who have yet to experience the realities of life, employment, or family responsibilities. Excluding young leaders from the fallen regime, is this interim government truly engaging with the public? Are they considering younger leaders who have been active in the field for years, like Andaleeve Rahman Partho, Zonayed Saki, Rumeen Farhana, or Nurul Haq Nur, popularly known as VP Nur, all of whom fought against the previous regime?

Is this government listening to critics popular with younger audiences, such as Pinaki Bhattacharya, Dr Zahed Ur Rahman, or journalists like Masood Kamal and Ashraf Kaiser? Are they paying attention to what these voices are saying now?

Those of us who support the interim government believe it's not too late. There is still time to achieve the reforms the people dream of before handing over power to an elected government. But the government must engage in dialogue with every stakeholder—experts in their respective fields—and act swiftly.

At the end of the day, time is money, and we cannot offer it indefinitely to this interim government. The people of Bangladesh are anxiously waiting for visible, practical changes: accountability, the formation of commissions, restoration of law and order, control of inflation and the prices of daily essentials, and the dismantling of corruption and syndicates. These are essential steps to establish fair, discrimination-free governance in every sector and to quickly reinstate a democratically elected government.

Muhid Bhuiya is a human resources manager at a multinational company in Dhaka.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments