A case for democratic reforms in universities

The recent mass uprising, which began as the quota reform movement, had a unique characteristic. In many public universities, including Dhaka University, we witnessed the ruling party's student body being driven away from the residential halls.

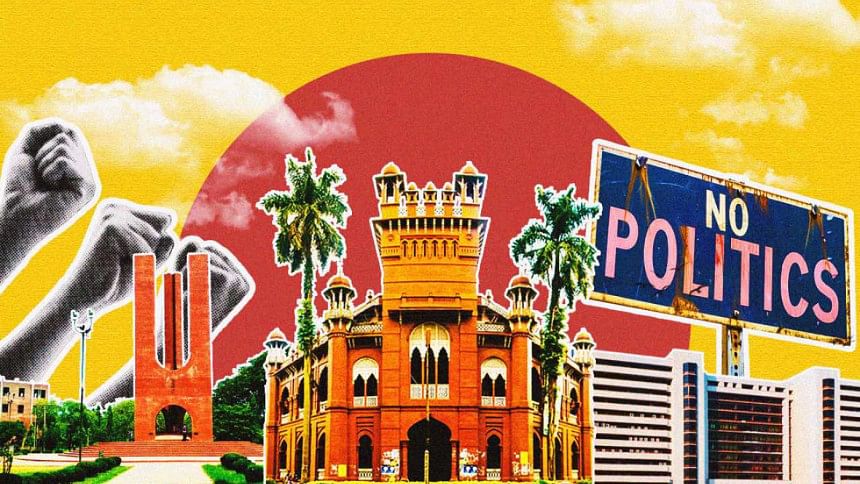

After the chaos subsided, during my regular morning walk, I noticed many new changes on the Dhaka University campus. In front of Mohsin Hall, I saw various belongings of Chhatra League members in the dumpster. I also came across a PVC banner that read, "Politics is banned here from this day. From now on, no one can force a student to attend a political gathering or the guest room."

The banner indicated that the anti-discrimination movement had given students a platform to unite and express their solidarity.

Living in a university residential hall traditionally provides students with opportunities to improve their lives, both academically and non-academically. Therefore, students who experience economic hardship often prefer to live in these halls, hoping to achieve their long-cherished dreams.

Unfortunately, until now, the halls had been transformed into places where ordinary students faced heavy oppression.

The halls had operated without a proper seat allocation system for students. The student wing of the former ruling party essentially managed the halls with unofficial authority, allotting seats to themselves. As a result, students lost their dreams and hopes, facing nightmares in their residential halls. This is how many "shikharthi" students become "gundarthi" (hoodlums). And the university administration's teachers have served as enablers in the transformation of bright students into goons.

Universities should be proper educational institutions in every sense, and student halls should be places where residential students can learn how to be fair and just in their social and educational lives. Now that a platform of unity has emerged among the students, they are endeavouring to erase their memories of living in such nightmarish environments. For that reason, the hall administration must perform the responsibilities of maintaining these halls, which is supposed to be a routine institutional practice.

The aforementioned PVC banner clearly exemplifies this. As discussed above, the two main demands were that no one should be forced to attend political programmes or be sent to guest rooms against their will. These are their biggest concerns, and they are trying to escape them. They are striving for a system where their dreams do not turn into nightmares and where the administrative system supports them in achieving their goals, completing their education, and doing something meaningful with their lives.

Autocracy, oligarchy, and dictatorship at the state level have enabled and even encouraged mismanagement in all forms of government and organisational structures. As such, universities are not exempt from this.

Whenever we talk about the 1973 Dhaka University Order that guides the university's operations, we take pride in it. We rightly appreciate that it ensures freedom of speech, expression, and the right to speak. However, it also inherently contains certain autocratic elements.

For example, as per the order, the Vice Chancellor (VC), in some exceptional cases, can overturn any rule, suggestion, or decision already made by any administrative body. But these "exceptional cases" have become everyday practices. This is just one example. Even in selecting the VC, his or her academic or administrative qualifications do not matter. The chancellor appoints him or her based on their political identity. The same goes for the recruitment of teachers.

If we examine the list of past provosts, we see how different they were from the current ones in terms of their wisdom and personality. Some of the current provosts did not even have the required qualifications to become teachers, yet they became provosts. This practice is not limited to provosts or VCs only; it also applies more or less to many of the administrative posts.

Partisan identity had become a deciding factor in their appointments. This does not mean that this factor was present only in the past 16 years. However, the former regime took this malpractice to an extreme and unparalleled level.

The same issues extend to the Dhaka University Teachers' Association.

As a bargaining agent, the Teachers' Association is supposed to negotiate with the university administration and the government for the best interests of teachers. There should be debates and negotiations from both sides. However, teachers who are already in administrative positions often contest elections for posts in the association with the advantage of easily getting votes from junior colleagues, which can lead to their election. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to discern who is making whom accountable and how.

After the fall of the Hasina-led autocratic regime, the opposition party is trying to re-establish its position. As a result, anarchy seems to be on the rise, with personal agendas and witch-hunting, targeting people who had associations with the ruling party in some cases. Without proper administration, it seems like students are preparing lists to decide which teachers will stay and who will not. The situation has become quite unruly in some places, with registrar's offices and other administrative buildings being targeted.

We are forgetting that this is an educational institution. Of course, teachers with allegations against them must be investigated, and justice must be served—there is no doubt about that. But all of this must go through due process.

Anarchy is not the solution. It will destroy the integrity of the university. If this practice continues, it will not ensure a stable environment for the university or government. What we need is creative leadership in the administrative process that brings back the original structure and upholds the spirit of the people's uprising and sacrifices.

The leaders need to create a structure and a plan with the goal of state reform. They should reform higher educational institutions, including universities, to establish a student-friendly, democratic administrative body that dismantles the autocratic structure. This will pave the way for a bright future for students and bring about a brighter tomorrow.

Dr Mohammad Tanzimuddin Khan is professor at the Department of International Relations in Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments