Citizens, elections, democracy: The Bangladeshi conundrum

Elections are a fundamental aspect, if not a pre-condition, for a democratic polity. However, while a democracy is not possible without an election, the simple fact that one has been held is no guarantee that democracy has been established. One of the greatest ironies for Bangladesh is that, though it has held elections with some degree of regularity over the last few decades, democracy has remained halting and elusive.

In fact, while elections elsewhere are typically occasions for demonstrating and reinforcing the spirit of constitutionalism, the rule of law and the supremacy of the people's will, elections in Bangladesh expose our gradual slide into an Orwellian universe which is simultaneously absurd and dangerous.

The age-old notion of "politics" as public service, for establishing the "common good," where "popular sovereignty" is upheld through a peaceful and transparent electoral process, has become increasingly irrelevant to the political dynamic here. Elections have become a desperate struggle through chicanery, intimidation, manipulation, violence or "whatever means necessary" to somehow get or keep power. It is not an occasion to be celebrated or for introspection, but a time of uncertainty, anxiety, and dread for the very people, the masses, that elections and democracy are supposed to serve.

While elections elsewhere are typically occasions for demonstrating and reinforcing the spirit of constitutionalism, the rule of law and the supremacy of the people's will, elections in Bangladesh expose our gradual slide into an Orwellian universe which is simultaneously absurd and dangerous.

Several concerns about the impending elections, or democracy in general, become apparent. First, major political parties do not view each other as opponents, but as enemies—or even as existential threats. There is a hyper-polarised and toxic environment where confrontation rather than persuasion has become the norm, and the rhetoric and actions of the major parties have become increasingly intolerant, aggressive and threatening. They are prisoners of their own exclusive and alienating narratives, and the elections are approached as a gladiatorial contest rather than political competition. Citizens are justifiably worried about the credibility of such elections and acceptability of the results.

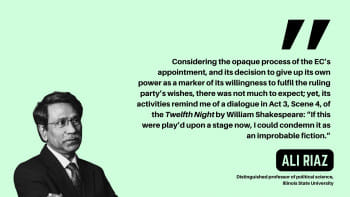

Second, that uncertainty has been exacerbated by the fact that the last two elections were woefully inadequate in satisfying people's democratic expectations. This time, too, the perceived lack of autonomy of the Election Commission (EC), its weaknesses revealed in local government and parliamentary by-elections, its arbitrariness in party accreditation decisions, its wasting of almost a thousand crore taka in getting EVMs which it cannot use, and its premature announcement of the election schedule, all sharpens that scepticism.

Added to that is the question of the huge number of political parties that exist—44 registered with the EC, and many others which are not. Most lack organisation, ideals or policy platforms, and merely represent a loose clustering of sycophantic individuals around a professed leader. These typically surface during election time jockeying for alliances and coalitions which are temporary, opportunistic, and cynical.

Even the dominant parties do not set an example by practising internal democracy: party elections or conventions are seldom held, and leadership patterns are determined by dynastic logic and nepotistic arrangements that are unchallenged and inviolate. None of this is conducive to sustaining the people's confidence in democracy.

Third, there are some systemic dysfunctionalities. This is reflected in one party's absolute control of the parliament (almost 90 percent belonging to one party), which robs it of its debate and oversight functions, and the dominance of business interests in the House (more than 60 percent of elected representatives define themselves as such), which compromises its broader considerations and obligations. Moreover, the parliament remains totally subservient to executive authority, leading to an unholy conflation of leader-party-parliament and state.

The independence and moral authority of the judiciary is also jeopardised because of its perceived organisational vulnerabilities, and the fact that partisan conflicts and physical skirmishes can flare up within the vaunted premises of the Supreme Court. Moreover, the courts are undermanned and overwhelmed with more than five million cases in the docket with thousands of others (including "ghost cases") added every day.

Even the universities, traditionally considered to be the bastion of progressive activism, thoughtful debate and optimism about the future, have been turned into cesspools of moral rot, intellectual stagnancy and fascist impulses.

Fourth, there is an apparent contradiction between "progress" (measured in clinically quantitative terms) and "development" (which has some "quality of life" factors associated with it). Thus, on the one hand, some focus on the obvious and impressive economic growth expressed both in terms of various social indicators and through several dazzling infrastructural projects.

Others point to the severe democratic deficits, erosion of civil liberties and human rights, curtailing of free speech, increasing levels of crime, corruption, pollution, inequality, unemployment, inflation, loan defaults, and foreign exchange crisis.

The resulting discourse, framed in either-or binaries, is predictably contemptuous of the "other" and has contributed to confusing the public and confounding its political expectations.

Finally, international tensions and geopolitical gamesmanship have also complicated matters. India has historically been active in preserving and extending its interests and controls in Bangladesh, and its political prejudices are, and have been, quite evident.

Recently, great power rivalries have also cast a shadow over the evolving situation here. The US has sought to influence the process through its insistence on dialogue and inclusiveness, ensuring the integrity of the elections, and shrewdly using US visa restrictions to nudge the process, fully aware that access to the US is crucial to the dreams and aspirations of a significant segment of the Bangladeshi elite (as a preferred place to park their children, their wealth and, when necessary, themselves). This newly-discovered eagerness to spread democracy is wholly inconsistent with its history in Latin America, or its efforts to "force people to be free" in the Middle East.

However, China and Russia have also gained considerable salience through economic, technological and project assistance they have rendered, and dangle tantalisingly. The conflicting interests and claims of these countries have introduced an additional level of fluidity and uneasiness into the situation (it must be pointed out that nothing flatters the colonised sensibilities of the Bangalee ego more than the feeling that they are considered important by the great powers).

Consequently, even though transparent, participatory and competitive elections are a constitutional right, the realities today have vitiated those expectations. Instead of serving the people, the parties appear to be holding them hostage to their own overriding agenda of self-promotion and self-protection.

The "spring of hope" we had experienced about 50 years earlier is gradually drifting towards a "winter of our despair" currently. Dickens was locating his novel in pre-revolutionary France with indications of radical developments later. The situation he described may well apply to Bangladesh today, and the outcome it led to, as Hamlet would say, is "a consummation devoutly to be wished."

Dr Ahrar Ahmad is professor emeritus at Black Hills State University in the US.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments