COP29 negotiations: The deadlock over cardinal issues

On November 21, several important issues including climate finance, mitigation ambition, Article 6 of the Paris Agreement about emissions trading, and loss and damage fund were discussed at the Conference of Parties 29 (COP29) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). However, this COP was supposed to be the COP of climate finance, as the Paris Agreement stipulated that by 2025 a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) had to be agreed upon, keeping the earlier target of $100 billion as the floor. In the last COP in Dubai, it was reiterated that a decision text has to be agreed upon about the NCQG at COP29. Climate finance is a cross-cutting issue. It is the enabler of all climate actions and has several dedicated agenda items, with NCQG being the most critical.

The third iteration was shared by the Azeri Presidency on NCQG on November 21. It was perhaps pushed by the UN Secretary General's request to leaders of the G20 meeting in Brazil so that they instruct their ministers attending the second high-level segment in Baku to reach an agreement on climate finance. The initial draft began with more than 150 paragraphs with many bracketed options and sub-options. The latest draft, as of writing this article, has 61 paragraphs, again with many bracketed options. The number one issue is the quantum—the NCQG. The developing countries are demanding an amount of $1 trillion to 1.3 trillion a year over a 10-year period, up to 2035, with mid-term reviews either in 2030 or 2031. This number is based on a minimum need for implementation of their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs).

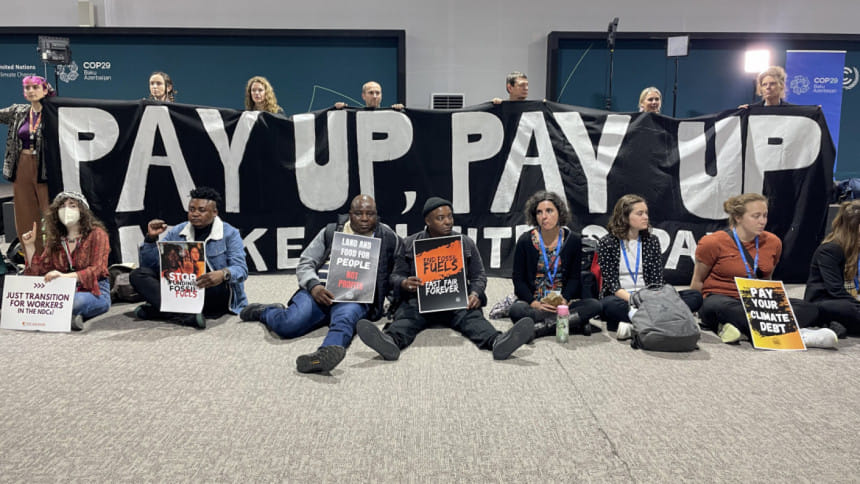

However, the implementation of climate actions in developing countries is estimated to require $6-8 trillion a year. Some analysts view this number as a kind of sleight of hand accounting. Some ministers from developed countries think that this amount can be mobilised from all sources—public, private and alternative sources. At the press conference, jointly organised by the G77 group and the African Negotiating Group on November 20, in response to whether they will accept $200 billion a year, the Bolivian delegate cynically referred to the amount as a joke. The Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are demanding $220 billion and $39 billion respectively a year in grant- and grant-equivalent terms. Further, they demand at least 20 percent of climate finance must flow through the Convention funds like the Green Climate Fund. So far, only about 2-3 percent of global climate finance flowed through these funds. These funds have better terms and access is relatively easier.

The global financial system is awash with liquidity. For example, in 2021-2022, fossil fuel subsidies amounted to $1.1 trillion and the annual military spending stood at more than $2.2 trillion in 2023. So, money does not flow where it is needed the most—to protect people and the planet from the existential threat of climate change. We may recall that just before the beginning of COP29, four authoritative reports were published by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), UNFCCC and World Meteorological Organization (WMO) about the gaps in emission reduction, gaps in adaptation finance and poor ambitions in the current set of NDCs. These reports served as wake-up calls for urgent actions to bridge these gaps.

There is also the issue of the quality of climate finance which includes the definition of climate finance, grants versus loans, access to finance, co-financing, etc, and is even more important than the NCQG number. The Bangladesh delegation loudly voiced concerns about quality-related issues, specifically the need for a definition of climate finance, as its absence allows developed countries to inflate their contributions through double and triple counting. Also, the grant versus loan issue is extremely important because more than half of the LDCs are already debt-distressed and climate loans further restrain their fiscal space. Most of the LDCs spend much more on paying interest against accumulated loans than they invest in education or health services in their countries. So, they strongly called for debt cancellation and debt relief for low-income countries. There is also a demand for the inclusion of contingency clauses in bilateral and multilateral loan agreements. Spain and Denmark in particular are supportive of the contingency clauses against disasters so that the impacted countries can get debt relief and debt rescheduling for longer terms. Related to this is the issue of reforms of multilateral financial institutions, which now provide about 45 percent of climate finance. However, the World Bank, in particular, which now hosts the Loss and Damage Fund, is not familiar with dealing with human rights and climate justice. The latest draft text included all these issues, but developing countries' demands remain bracketed.

The draft also included sources of mobilisation—bilateral, multilateral, alternative, innovative and philanthropic. It mentions innovative sources like debt for nature swaps, local currency financing, etc, but they are not detailed. Past experience of debt for nature swaps is not encouraging, since it involved paltry amounts and the benefits were largely appropriated by the intermediaries, which did not strengthen the debt sustainability of the recipient countries. I have published a paper on debt-for-adaptation-swap at bilateral levels, where deals can be reached quicker than at multilateral levels, which are very cumbersome and time-consuming.

The second most important issue of this COP—full operationalisation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement—about emissions trading still hangs in the balance due to differences in ensuring transparency about detailed information to be posted in the UNFCCC portal called agreed electronic format. My article on this issue was published in The Daily Star at the beginning of this month.

The negotiations extended beyond November 22, as in the past few COPs. The strategy, particularly of the developed world, is to wean out all the energy and appetite of small delegations from most of the global south. Also, there is a "wait and see" policy of how developments unfold at the last hours when some numbers and compromises are agreed upon to wrap up. Being a negotiator with the Bangladesh delegation for over two decades, I call these negotiations a process of "active inaction." For the right reasons, Bangladesh's Chief Adviser Prof Yunus has called for downscaling these jamborees, which have an average presence of more than 70,000 delegates both from governments and observer organisations. The sooner this happens, the better.

Mizan R Khan is a board member at Scientific Council of COP29 Presidency, visiting scholar at Brown University, and technical lead at LDC Universities Consortium on Climate Change (LUCCC).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments