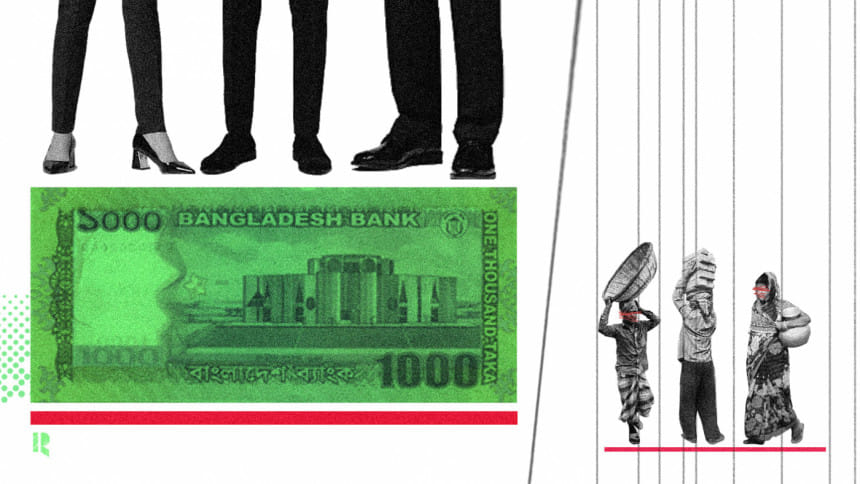

A country for the rich, and another for the poor

In recent years, Bangladesh has been grappling with a deepening chasm of inequality. While on the surface, macroeconomic indicators like GDP and per capita income have shown growth, the reality paints a starkly different picture.

The majority of Bangladeshi families continue to struggle with monthly incomes far below the newly-elevated per capita income in the country, which is claimed to be nearly $2,800 per year in 2023, or around Tk 25,000 per month. This means a family with four members is supposed to earn Tk 1 lakh a month, but the harsh reality is that most households barely manage to make Tk 20,000 to 25,000. The rest of the supposed income clearly lands in the pockets of a few selective groups. This troubling disparity has been a long-standing issue, but in recent years, it has grown so pronounced that it's as if two distinct economies are operating side by side in the country.

For the vast majority of the population, expenses are climbing upward, real incomes are dwindling, and overall participation in the broader economy is waning. In sharp contrast, a small minority enjoys exponential growth in both nominal and real income. This group also accumulates assets at an astonishing rate while significantly influencing the overall economic landscape.

If we look at government documents (Household Income and Expenditure Survey of 2010 and 2022), we find shocking evidence of this divide. In 2010, the top five percent of earners of the population possessed 24.61 percent of national income, while the lowest-earning five percent held a mere 0.78 percent of the income. This translated to more than a 30-fold difference between the highest and lowest earning groups. Twelve years after 2010, the lowest earners' share shrunk to 0.37 percent, while the highest earners saw their share grow, from 24.61 to 30.04 percent. Disparity further widened, more than 80 folds, perpetuating an alarming trend of escalating inequality and creating a sharply polarised economy. The surveys also revealed a concerning trend – only the top 10 percent of the population has witnessed an increase in real income, while the remaining 90 percent saw their income stagnate or even decline. We must keep in mind that only legally declared income of the wealthy group is accounted for here.

So, what fuels this ever-widening gulf? A substantial part of Bangladesh's population, including over five crore labourers in the informal sector, contends with precarious and limited income. A percentage of factory workers receive fixed wages that barely keep pace with inflation, leaving them grappling with financial hardship. Farmers and rural workers face extreme insecurity, and other income groups, including many professionals, teachers, small traders and media workers, are also seeing their real income going down.

In contrast, the minority that centralises wealth experiences a huge surge in their income. Recently, for instance, the garment owners benefitted immensely from the devaluation of the taka, reaping substantial profits due to fluctuations in exchange rates. In sectors tied to the dollar, such as energy and power, a select few enjoy huge profits, while the majority bears the brunt of financial strain. Construction projects underscore this wealth disparity through their extravagance, inefficiency, and propensity for money laundering. Overspending and corruption result in astronomical costs, further exacerbating the inequality gap. Bangladesh now boasts a group of families, which have accumulated a mountain of wealth, similar to what we saw during the Pakistan period. Through the profits reaped within Bangaldesh's borders, these affluent individuals have managed to establish themselves as some of the wealthiest in other countries. What's more striking is the preferential treatment these ultra-rich individuals receive from the government.

This economic polarisation has sown seeds of anarchy, destabilising the economy and subjecting the majority to immense pressure. Over the past few years, inflation has soared, impacting the majority; expenses for essentials like food have surged by 20 to 30 percent. The Covid-19 pandemic compounded these challenges, leading to job losses, depleted savings, disrupted education, and soaring medical costs; and now, the price hikes are just adding to the misery. The dengue outbreak adds another layer of adversity for the working class, as medical treatment remains expensive and inaccessible. Public hospitals are struggling to cope with the influx of patients, and authorities have been slow to respond. High cost in private hospitals and price hike of medicine and saline have made matters worse. Strikingly, the government's absence is often noticeable when public interest needs protection, but its presence is visible when protests and dissenting views are being suppressed.

As we delve deeper into the socio-economic fabric of Bangladesh, it's important to recognise the multifaceted nature of this crisis. The roots of inequality extend beyond the economic sphere and touch various aspects of daily life, from healthcare to education, housing, transportation, security, employment and beyond. The situation has grown so pronounced that it's no longer a mere issue of income inequality; it's a crisis of access, opportunities, and basic necessities. While public infrastructures are in a dire state, the private sphere – luxury items, cars, food and entertainment – is becoming increasingly lavish by the day.

This discrimination and polarisation have left the majority vulnerable, with nowhere to seek refuge. They, the true owners of the country, feel disheartened, persecuted, and ostracised in their homeland. On the other hand, the rich minority, who keep their assets outside the country, now wield significant influence within it. The situation takes a darker turn when the government lacks transparency and accountability. Such disparities are not just confined to specific sectors; they are deeply entrenched in the very fabric of our society. It's reminiscent of the regional disparities that once plagued Pakistan, where East and West Pakistan were distinguished by economic inequality. Bangladesh had fought against this discrimination and gained independence, but now, it grapples with discrimination within its own borders.

As told to Monorom Polok of The Daily Star.

Anu Muhammad is a former professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments