Crossing the Padma

I was an anxious young boy of 13 when I first faced the River Padma. It was in April of the momentous year of 1971 when a murderous campaign turned asunder the land.

Known as East Pakistan for an interim period, the land historically was Vangala, Bangala, Banga. Like many others that treacherous month, my father fled Dhaka city taking us to the banks of the Padma so that we may cross to the other side for safety. It was perhaps like crossing the river Styx in Greek mythology, but in a reverse order: from the world of death to a safer life.

The river appeared incomprehensible and infinite, generating a primal terror in me.

Here was a river that was larger than life, larger than anything I had encountered before. Flowing gloriously and indifferently, the river presented a mythic scale against which I felt terribly puny. And terrified. That sense of terror on facing something sublime was magnified by the other terror, something more insidious and menacing, the onslaught of the Pakistan army that forced my family to arrive at the banks of the river, to seek a safe haven on the other side.

Between the two sides flowed the waters of the mighty river that has received many names and appellations. Ganges. Ganga. Padmavati. Padma. Padda. Boro Ganga. Kirtinasha. Mahasindhu. Oceanic. Beautiful. Treacherous. Nagini. Tempestuous. Unfathomable. Shorbonasha.

Poets and song writers have lyricised its waves, and writers and navigators have tried to plumb its oscillating depth.

From where we stood on the banks that April in 1971, the other side was a tantalising line on the horizon. Another tantalising line now crosses over the river – a 6.15 km long human installation by the name of Padma Bridge. An incredible engineering operation, surpassing political, economic, and obstructionist challenges, the bridge presents the audacity of a new Bangladesh.

On a sunny day in October this year, I crossed the bridge with a group of friends. Gliding over the new construction that snakes over the river, I imagined two streams of flow – the aquatic and the bridge traffic – that crisscross without touching each other. A bridge and a river form a mystifying bond that the German philosopher Martin Heidegger saw as the junction of the fourfold, in which "earth, sky, mortals and divinities" come together to reveal a special place for human dwelling.

Crossing the Padma is close to a transcendental experience that invokes the intersection of geological time with human history. In the millions of ferrying of boats, barges, and bajras, perhaps the Charyapada poet Bhusukapada's crossing of the Padma is the most significant. In one of his poems, Bhusukapada describes his crossing as akin to becoming a "Bangalee." The Charyapadas were written between the 8th and 12th centuries as part of Buddhist esoteric practices, but they also reveal the social life of eastern Bengal. In the song-poem, Bhusukupada arrives from the other side of the Padma in a bajra, and while ravaging the land, becomes a Bangalee instead. This he does, he admits, by crossing the Padma and marrying a "chandal," a local woman. A momentous story of crossing and becoming.

There are other memorable accounts of crossing the river. In the 11th century, the Pala king Rampal would cross the Padma from western Bengal with his mighty navy fleet to fight the Kaibartas, the fishermen community, who had overthrown the Palas and taken over the land of Varendra in arguably the first peasant revolt in India. The Kaibartas were eventually defeated. In the 16th century, the Mughal minister Abul Faz'l came down the river from northern India, and crossed over to the quieter Ichhamoti river to travel to Dhaka. He is the one to speculate that the name Banga-al is derived from the "al," the small dykes made by farmers in this land. If this is a fact then the name of the land is forever attached to an agricultural ethos.

James Rennell, the famed British cartographer who made the first comprehensive topographical map of Bengal, sailed from Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1764, again on a bajra, to find a navigational path to Dhaka. The colonial intention was of course directed by an exploitative need to know and plot every square inch of the land even if it was all liquid terrain. Rennell first travels south through various rivers and channels, almost to the Sundarbans, and finally moves up to reach the Padma. He calls the river "Boro Ganga." He records the flow and the banks to create the first accurate cartographic representation of the mighty river. His map of the Kushtia-Pabna reach of the river describes the first geographic attempt to understand the char dynamic. He also crosses the Padma from the south to enter the quieter river Ichhamoti in order to reach Dhaka.

Sailing on the same waters, the poet Rabindranath Tagore would apply a different lens to gauge the river. Going back and forth between two zamindari estates on two sides of the Padma, the poet would traverse the rivers and canals and pen his finest thoughts on nature and landscape in many songs and letters.

Some one hundred years later after Rennell, the British introduced a new technology that changed the landscape forever – the railway. Swinging like serpentine tentacles across the land, the railway line was the progenitor of bridges across the river. To link Assam and northern Bengal with Calcutta, the colonial administration created a railway network that was served by ferries for river crossings. Historian Tariq Ali describes the endeavour as part of the "colonial conquest of Bengal." The Eastern Bengal Railway connected Calcutta and Dhaka through a combination of rail and river link; trains from Calcutta reached Goalundo from where passengers would take the famous steamer service to reach Dhaka. Completed in 1915, and completing the colonial rail project, the Hardinge Bridge was the first bridge crossing over the Padma.

Crossing the Padma is an invitation to an immersion in the geographical and political history of the land. We come to know a few things: that the Padma is the Ganges, and Padma is not. When the Ganges bifurcates at a point a few miles west of the political boundary of Bangladesh, it creates two streams of distinctive ecological as well as cultural regimes – the Hooghly-Bhagirothy that claims the name and aura of the Ganga, and the Padma that inherits the bulk of the Gangetic flow (Amartya Sen, in his memoirs, describes the rivers as two charismas). In carrying the waters of the Ganges, the Padma becomes the last leg of the mighty and mythologically-charged Ganges. In the Padma, the Ganges is reincarnated into a "new grandeur," and that is perhaps why the name evokes the lotus flower.

Unlike other rivers in the land, the Padma draws us to the ancient reservoir of our existence, for it is the very theatre of the creation of land and life. The Ganges in becoming the Padma, and joined by the Jamuna, unleashes a dynamic that also creates the largest delta in the world. Certainly, the river not only defined Bengal, its life and landscape, it literally gifted the land that we call Bengal and now Bangladesh. For the Padma is not simply a flow of water, it is a monumental cascade of silt and sediment. Each year the Ganges-Padma brings 400 cubic billion tons of silt to the delta. An English geographer estimated that it is equivalent to 350 pyramids the size of Giza. Writers have described this great churning that sustains lives in both Bengals as the Padma Process or the Padma Dynamic.

Geographers now describe how the Gangetic-Padmatic flow does not simply end at the coastal rim, at what is better known as the Meghna estuary. The slow flow of the sediment continues under water in the Bay of Bengal, and almost to the Equatorial Line in the Indian Ocean, creating an underwater liquid land – known as the "subaqueous delta" – that is bigger than the size of the two Bengals combined. Known as the Bengal Fan to geographers, it is an alluvial theatre of cosmic proportions.

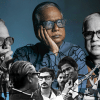

Some 60 years later, coinciding with 50 years of the nationhood of Bangladesh, I am faced with the Padma again. This time, the anxiousness has turned into anticipation – the release of an enchanting book, The Great Padma: The Epic River that Made the Bengal Delta (ORO Editions, 2023). The work of writers, historians, geographers, anthropologists, architects, and photographers were assembled to reveal the ecological and human horizon of the glorious river that touched: The hilsa. The Goalundo Chicken Curry. The steamer. Bhatiali. Kuber the Padda Nodir Majhi. The Padma Bridge. Receiving the printed book in my hand, I felt I was on the banks of the river, as I was that first time, with the same sense of awe and wonderment.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and architectural historian, and editor of the forthcoming book "The Great Padma: The Epic River that Made the Bengal Delta."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments