Educators are in need of ethical guidelines

Many academic institutions play up their ethical identity by overtly promoting honesty, integrity, transparency, accountability, confidentiality, objectivity, respectfulness, and obedience to the law. Unfortunately, these bastions of moral high ground seem to have been breached with serious moral decay, across the board.

Administrators are accused of nepotism, financial improprieties, being in cahoots with wayward and politically connected (student) leaders, and a mix of other indiscretions and misdeeds that are growing steadily. Historically, such accusations have been a rarity and the consequences dire.

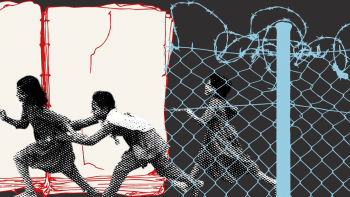

A wayward student body is also depicted today in the media, reflecting how far and deep the rot has spread in academia: from lack of preparedness for higher education, irregular class attendance, and disrespectful demeanour, to indiscriminate violence, substance abuse, mugging, gambling, sexual predation and more.

This writing is about teachers. A casual survey reveals the many areas in which breakdown in ethics is widespread in our educational institutions:

* They are already smeared for unfairness, intemperate behaviour, plagiarism, cosy relationships with political muscle, and pecuniary interests that are incongruous with their academic character. Research and scholarship for many have simply gone with the wind!

* Their involvement with students (and staff) in ways other than a mentor-mentee relationship includes inappropriate and informal communications.

* Social intolerance and disrespect in academia is growing, especially concerning political or religious ideology.

* Course curricula are barely revised in years. What is an academic institution without a vibrant curriculum tailored to stakeholder needs?

* Teachers conducting research with students exploit the relationship without sharing the value of such research or the methods employed. Instead of preparing them to become potential researchers, teachers use them as data collectors to build their publication profiles. Thus, students fill out questionnaires at home, seriously muddling the study.

* Classrooms often become marketplaces where teachers peddle their own books, persuading students to purchase them.

* Inability to reach an instructor at their desk is a persistent problem, especially when students require extra care to overcome their learning challenges. Teachers also miss classes without an acceptable excuse.

* Cases of sexual impropriety, domestic violence, assault episodes or embezzlement of funds are also not unheard of in academia.

* At seminars, conferences or academic events, teachers chat among themselves, use their phones or pay little attention to the deliberations. If they are not effective learners at these academic events, can they expect such behaviour from their students?

When academic institutions elsewhere are striving to bring out the best scientists, economists, educationists, etc who devote their lives pursuing, disseminating and using knowledge, how do our academics measure up? As numerous transgressions of ethical norms in academia go unheeded, it is imperative to revisit the question of ethical conduct and appropriate guidelines for our educators.

Such a concern stems primarily from the realisation that it is the teachers who will be in primary contact with the next generation. If their values and behaviours are compromised, what does the future portend? With the education system in peril – and with that the society itself – where are the guidelines? How are they enforced?

For teaching to be considered a noble profession, Bangladesh needs a strong and ethically driven education system today. If we have to educate our educators on ethical practices, we must collectively start working now to produce/prepare the next generation who will not need a programme on ethics for teachers. Until then, to shape appropriate academic behaviour, we must figure out essential ethical guidelines and the ramifications for any transgression. We know quite a bit about the transgressions, but very little about how they are confronted and addressed. Without consequences, as BF Skinner – the proponent of operant conditioning theory – would say, repetition of unethical behaviour will only recur.

To be fair, the question of ethics goes far beyond the borders of educators and the education system. Not a day goes by without being accosted by some ethical confrontation with the gatekeepers and power brokers who scorn ethical norms – in healthcare, law and justice, bureaucracy, banking, business transactions, etc. The waft of moral decay is already palpable; some sense that it is poised to worsen. When a nation's moral structure crumbles, society will also crumble with far-reaching consequences. Showcasing the economy with spectacular physical infrastructure development has its limits; combined with a steel frame of moral strength, the potential of advancement may be limitless.

Dr Syed Saad Andaleeb is distinguished professor emeritus at Pennsylvania State University in the US, former faculty member of the IBA, Dhaka University, and former vice-chancellor of Brac University.

Sanjana Rahman is lecturer at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB) and a doctoral candidate at Universiti Putra Malaysia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments