Food security before Covid and now

Bangladesh has made significant strides in several socioeconomic development indicators over the last 30 years. However, the Covid pandemic, as in the rest of the world, has caused disruptions in the country's development trajectory. Additionally, once the worst of the pandemic subsided, inflationary pressures resulting from the Russia-Ukraine war further complicated Bangladesh's development dynamics, particularly in the context of poverty reduction, inequality, and food security. In this conjecture, it is important to gauge how Covid-related and post-Covid challenges have affected these parameters. The recently completed Sanem-GDI Household Survey 2023 produced some important insights in this regard.

In 2018, the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (Sanem) conducted a nationally representative survey covering 10,500 households across Bangladesh. During October-November 2023, Sanem—in collaboration with the Global Development Institute (GDI) of the University of Manchester—conducted another round of surveys with the same sample, successfully covering 9,065 households. Based on the survey findings, four key issues are noted.

First, we observe that the national upper poverty rate fell from 21.6 percent in 2018 to 20.7 percent in 2023. This fall in poverty is primarily driven by the fall in rural poverty from 24.5 percent to 21.6 percent. However, we also observed a rise in urban poverty rate, from 16.3 percent to 18.7 percent.

Given the depth of the pandemic crisis, the income-based poverty approach might not capture a holistic picture. In this regard, we estimate the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). The MPI is constructed based on three indicators: (i) education, (ii) health, and (iii) standard of living. Bangladesh's MPI headcount poverty rate fell from 25.8 percent in 2018 to 24.7 percent in 2023. The rural MPI poverty rate fell from 30.4 percent to 27.6 percent. However, the MPI poverty rate increased in the urban areas from 16.8 percent to 18 percent.

In the face of rising urban poverty and food insecurity, there is no alternative to widening the existing social security programmes in the urban areas. At the same time, programmes like open market sales (OMS) or food-friendly programmes need to be further expanded. Moreover, the education ministry must undertake an action plan to address the concerns of the increased proportion of children outside education/dropout rates and recoup the learning loss impeded during the pandemic.

Why has poverty in urban areas increased? There are two possible explanations. First, urban areas constitute a large proportion of the vulnerable poor who migrated to the cities out of poverty or due to climate shock, etc. Significant shocks, such as the ongoing price hikes, would make these vulnerable people fall below the poverty line. Existing social security programmes do not cover urban areas extensively—making many urban households more vulnerable to shocks. Secondly, we observe a wide disparity in household consumption expenditure patterns between poor and non-poor households. In the face of post-pandemic inflationary pressures, poor households reduced their spending on food and non-food consumption expenditure. However, richer households have increased their spending significantly. Such disparity signals a rising inequality in the country. As observed, the share of income of the top five percent of the households compared to the bottom 20 percent increased by more than twofold between 2018 and 2023. Of course, our survey does not include ultra-rich households and, therefore, can be considered a conservative estimate. Nonetheless, the estimate shows a grim picture of growing inequality in the country.

The third most important factor we have observed is in the case of education. The prolonged closure of educational institutions during Covid pandemic contributed to a great level of learning loss. The opportunity to participate in online education/distance learning was limited during the height of the pandemic. Only 33 percent of urban and 21 percent of rural households had such access. But after schools did reopen, 15 percent of school-aged children were not attending schools in 2023. This is a two-percentage point rise compared to 2018. Moreover, this rate has increased among the lowest-income households while decreasing in the highest-income cohort. As such, almost one-quarter of the children from the poorest 20 percent of households are not attending school, compared to only nine percent of children from the richest 20 percent of households.

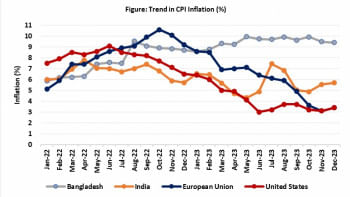

The final but biggest challenge most households in Bangladesh are facing in the "post-pandemic" era is the inflation rate. To cope with the crisis, households have resorted to changing dietary patterns, increasing borrowing, depleting savings/assets, cutting down non-food expenditures, etc. We found that the households' food insecurity, as measured with the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), worsened between April and October/November 2023. The food security of the poorer households worsened more than that of the non-poor households. In October/November 2023, nearly 22 percent of all households were moderately food-insecure, and three percent were severely food-insecure. Among the poor households, 30 percent were moderately food-insecure in October/November 2023 (a rise of five percentage points compared to April 2023), and seven percent were severely food-insecure (a rise of three percentage points). In all cases, we observed more severe food insecurity in urban areas than in rural areas.

These findings warrant urgent policy directives. In the face of rising urban poverty and food insecurity, there is no alternative to widening the existing social security programmes in the urban areas. At the same time, programmes like open market sales (OMS) or food-friendly programmes need to be further expanded. Moreover, the education ministry must undertake an action plan to address the concerns of the increased proportion of children outside education/dropout rates and recoup the learning loss impeded during the pandemic.

Finally, the government should explore more options for reducing inflationary prices in Bangladesh. Increased monitoring of the market alone cannot counter this crisis. It must be combined with supply-side policies, such as liberalising the import tariff for some essential food products, at least temporarily. Bangladesh is one of the most protected countries in the world, with high import tariffs and supplementary duties on almost all food products. So, there should be proportional monetary and fiscal policies to mop up the inflationary pressures on the economy.

Dr Selim Raihan is professor of economics at the University of Dhaka and executive director of South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (Sanem). He can be reached at [email protected]

Mahtab Uddin is assistant professor of economics at the University of Dhaka and a Commonwealth PhD scholar at the University of Manchester. He can be reached at [email protected]

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments