Inflation is yet another blow to education recovery

Shortages of essential commodities, including staple foods, have hit countries with inflation not seen in decades. Bangladesh has been hit hard, too, and marginalised groups are suffering the most. In addition to pandemic effects and the Russia-Ukraine war, unusual levels of flooding, unseasonable rains and cyclonic storms – likely effects of climate change – have placed a large number of people in great distress.

A World Food Programme (WFP) survey in Bangladesh, published on October 14, found 88 percent of the respondents to be under distress for the past six months due to increased prices of essentials, including food. Nasima Akhter, a garment worker in Savar and her two school-going daughters, used to live on a total monthly earning of Tk 14,000. But now transportation, her children's school costs and prices of essentials have gone up by Tk 3,000, leaving a gaping hole in her monthly budget. She cut back on food and occasional weekend outings with her children. A constant worry about expenses replaced the relative comfort she enjoyed.

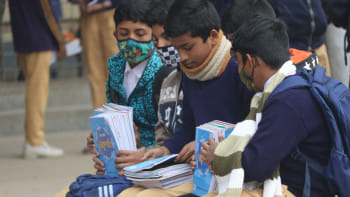

The owner of a school supplies store in Dhaka's Nilkhet area reported that a 200-page notebook that cost Tk 40 four months ago now costs Tk 50; a Tk 5 pencil is now priced at Tk 7; a Tk 65 geometry box is now sold at Tk 125. The cost of photocopying is up by 20 percent.

Of course, it's not just school supplies. Expenses for transportation to school, snacks and the almost mandatory private tutoring have kept pace with or surpassed the inflation rate.

The month-on-month inflation rate for August and September submitted to the planning ministry by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) surpassed nine percent, with food crossing 10 percent – the highest in over 11 years, as reported by the media.

The South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (Sanem), based on its household survey at the end of 2020, found that the country's poverty rate had almost doubled – from 21.6 percent in 2018 to 42.0 percent – while the lower or "extreme" poverty rate tripled from 9.4 to 28.5 percent. Observers suggest that the situation has improved somewhat since the worst of the pandemic has passed. But many also believe that the lingering effects, aggravated by natural disasters striking several parts of the country as well as the Russia-Ukraine war, severely blunted our economic recovery. The lowered projections for economic growth by multilateral bodies for 2023 say as much. BBS has not provided any updated estimate of income and poverty status or trend.

Assuming generously that one-third of the families in Bangladesh may be counted now as poor, this amounts to some 14 million families with at least 14 million students in poverty. This is very likely an underestimate of students in difficult economic circumstances, because this category includes many middle-class families who may not be categorised as poor.

The Education Watch 2021 report outlined a post-pandemic education recovery plan. It urged:

1. Urgently implementing a two-year learning recovery plan beyond the current year, including a grade-wise core skills assessment leading to steps to bring students up to minimum grade-level competency. A shift in school calendar to September-June with a fixed summer recess has been argued to have climate-related justifications, and that it can smoothen the logistics of implementing the recovery plan.

2. Deploying financial and other resources for the recovery plan and expanding school feeding schemes to bring back students from disadvantaged and low-income households and keep them in school, and prevent early marriage and child labour.

3. Expanding the blended learning approach: low-tech modalities such as interactive radio, SMS, interactive voice response, and offline apps which run on simple phones should be elements of a blended approach that combines and links classroom instructions and remote learning.

4. Providing funds for the recovery and remedial plan to support both government and non-government schools, teachers' incentives, school budget support, and working with NGOs, especially on recruiting and supporting voluntary parateachers.

5. Adapting decentralised and participatory implementation of recovery/remedial plan through working groups in each upazila and union, involving education personnel, local government, education NGOs, and teachers' organisations.

6. Forging partnerships between government, NGOs and the civil society to create a social compact for building education better.

The education authorities need to go back to the drawing board instead of insisting on denying the severity of the problem and doggedly trying to go back to the normal school routine. It is necessary to ask again if children are entitled to school education of acceptable quality, which the state is obligated to guarantee through public institutions or in collaborative arrangements with non-state providers. Or is education another commodity in the market, acquired by the highest bidder?

An International Monetary Fund (IMF) delegation led by Rahul Anand, head of the Asia and Pacific Department, is visiting for two weeks to negotiate a loan for Bangladesh. It is intended to be a budget support package from IMF's Extended Credit Facility on condition that necessary policy reforms in the economic and financial sectors of the country are undertaken. The loan amount under discussion is reported to be USD 4.5 billion, in addition to USD 1 billion by the World Bank. Could the reform agenda encourage measures to find and use resources for rescuing and reviving Bangladesh's education sector?

But then, is more money the main remedy for our educational woes? Given the implementation capacity of the education authorities, affected by poor management, lack of due diligence and corruption, one cannot be confident. Involvement of education NGOs with demonstrated capacities in planning and implementing a recovery plan can help.

Our policymakers have not listened to pleas along this line. The NGO Affairs Bureau under the Prime Minister's Office seems to look upon NGOs as adversaries rather than partners. The attitude seems to be: you are guilty until you prove yourself to be innocent.

Can a way be found to cut through the layers of these problems that our education sector is engulfed in?

Dr Manzoor Ahmed is emeritus professor at Brac University, chair of Bangladesh ECD Network (BEN), and vice-chair of the Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments