Column by Mahfuz Anam: Looking at Bangladesh through the minorities’ eyes

We liberated our country to establish – according to our constitution – democracy, socialism, nationalism, and secularism. Socialism, we discarded a long time ago. Nationalism, we never talked about much after independence. Democracy, we are in the process of discarding. The last, secularism, we never knew what to do with it. We liked it as an idea, but were never clear as to what it meant, how to translate it in our sociocultural context, and how to implement it in any sustainable manner. We never had the sincerity and the courage to pursue it with any degree of firmness. On occasions, we paid lip service to it, but more often than not, we looked the other way when the idea was torn to shreds and members of minority religious groups were victimised under one pretext or the other.

Religious strife – commonly termed as communalism – has a long history in South Asia. The Indian subcontinent was partitioned to solve the Muslim-Hindu question and bring about intercommunal harmony. Pakistan could never get out of its clutches; in fact, it never tried. India appears to be getting deeply into it once again. For Bangladesh, we came out of Pakistan to build a society of religious harmony, among other things. Now ours is a story of slipping away from our founding ideals.

Read more: 'They attacked us because we are Hindus'

On the question of religion, our position is very clear. Everybody has the right to be proud of his or her religion. But nobody has the right to hate, condemn, insult or denigrate the religions of others. This fundamental belief is what distinguishes us from the Medieval Age or even early Modern Age. Religious tolerance is a core achievement of modern civilisation, and its meticulous implementation is the basis upon which a world of peaceful coexistence can be built.

Religious tolerance is the most important value which a modern society must instil within itself, and Bangladesh is no exception. What we are noticing with increasing alarm is that, while exhibiting pride and respect for our own religion, we seem to think nothing of insulting that of others. In fact, the truth is darker still. Insulting others' religions or punishing followers of a different religion seem to have become a part of showing pride for our own.

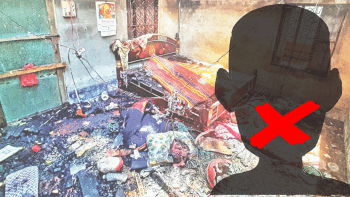

The happenings in Narail are the latest reminder of the fact that we have not been able to build a society of religious tolerance. For the minority communities, the issue is one of life or death, of survival or being perished, of living with dignity or servility. It is not something that you switch on and off. The fear remains, the lack of confidence in the future destroys dreams, and the fear of recurrence slowly but decisively overwhelms.

Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), a human rights and legal aid body, stated, based on newspaper reports, that from January 2013 to September 2021, a total of 3,679 instances of violence against minorities occurred across Bangladesh, varying from mob attacks to setting fire to their houses or shops, to vandalism of various kinds. In some instances – thankfully very few – even death occurred.

A cursory analysis of the big incidents of communal violence reveals a pattern of planned onslaught against minorities. The massive attacks in Ramu, Ukhiya, and Teknaf (2012), Nasirnagar (2016), Bhola (2019), and Sunamganj, Chandpur, Cumilla, and Rangpur (2021), with the latest incident in Narail (all attacks were on Hindus, except the ones in Ramu, Ukhiya and Teknaf, which saw the destruction of 19 Buddhist temples) – all of them bore striking similarities that cannot be easily explained away.

First, almost all of these incidents originated from a Facebook post showing a member of a minority community allegedly disrespecting Islam. This post was then made to go viral, generating severe reactions – mostly orchestrated – among the majoritarian community, leading to public gathering, demonstration and subsequent violent attacks. In most of the cases, the "insulting" Facebook post was found to have been fake, implanted by a hacker – a fact that did not seem to have any impact on the perpetrators of subsequent attacks.

Second, once the fake Facebook post becomes viral, protest groups form in no time, provocative speeches are made, slogans are uttered to instigate anger, and then demands are made for the arrest and punishment of the alleged culprit. However, without waiting for police to take action, the agitating groups take the law into their own hands and go into action. Within no time, things get out of hand and violence breaks out.

Third, once the stage is set, houses and shops of minority groups are attacked. It starts with an attack on the house or property of the alleged culprit, but soon it becomes an attack on the community as a whole.

Fourth, nobody raises any questions about the authenticity of the Facebook post, especially when previous examples of such hacking exist. Also, the fundamental injustice of punishing the whole community for the alleged crime of a single person is never raised.

Fifth, police in most cases play a very curious role. Either they take too long to appear on the scene or, if they are prompt enough to arrive, they never take a decisive action to nip the violence in the bud. This mysterious behaviour of the police has never come under questioning.

The Cumilla incident is quite extraordinary. Someone – police later caught the person – goes to a puja mandap at night and places a copy of the Holy Quran at the feet of an idol. Later, early in the morning, another person with a smartphone starts a Facebook live coverage of the scene showing the desecration of the Holy Quran and instigating people to take action. The curious thing is that a police officer, who had arrived on the scene, did nothing to stop him.

If we start with the happenings in Ramu in 2012 and come to the latest incident in Narail, over the last 10 years, the same narrative and same technique – social media posts or livestreams – have been used to trigger violent attacks on the minorities. Is there no lesson to be learnt? Why have the massive advancement in our capacities for surveillance and instant response not been used to prevent communal violence?

The most damaging and disheartening aspect of these recurring tragedies is that no fully fledged legal process has been completed even in one single case. This prevented the whole story from coming out, and prevented the persons and forces responsible from being exposed and punished. In most cases, some initial arrests were made and the story ended there, save perhaps some innocuous follow-ups that revealed nothing. Till today, we never came to know the full story as to how, by whom, and why these attacks occurred. This lack of legal action has created an atmosphere of impunity, encouraging the forces whose aim is to destroy communal harmony.

So, at 51, what is the Bangladesh that we have built? The economic story remains strong, with some questions reappearing due to the present global turbulence. The democracy story is dimming. However, we must put in greater efforts to make our tolerance story stronger. In Bangladesh, Muslims are not only the majority, but an overwhelming one – at 90 percent. This imposes special responsibility on them to ensure that minority rights are protected and observed at every level.

This we need to do not only for the sake of our minorities, but more for our own sake. Once the culture of hatred enters the psyche, it seldom leaves. It proliferates and engulfs the whole society and us as individuals. Surely, that is a Bangladesh we do not and cannot want.

Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments