Misinterpreting threats of visa ban won’t do us any good

The welcoming reactions from the mainstream opposition parties to the recently announced visa policy by the United States for Bangladesh was predictable, as they have been relentlessly complaining about the systematic destruction of a credible electoral institution. But the often confused reactions from the government and the ruling party seem surreal, as if this foreign intervention in favour of a free and fair election in the country is a blessing for them, too. The official reaction given by the foreign ministry was so welcoming that Matthew Miller, spokesperson of the US Department of State, said, "We were heartened by the announcement from the government yesterday (May 24) that welcomed the steps that we took."

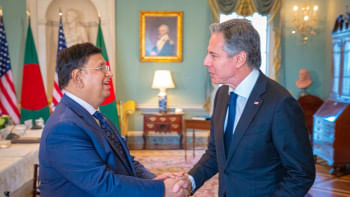

The foreign ministry statement, perhaps, was symptomatic of the consistently inconsistent statements made by the minister-in-charge. We have heard countless times from Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen that his government does not want any country to get involved in Bangladesh's internal affairs and that elections are in our DNA. But he did tell his US counterpart, Antony Blinken, that they could see if they could get the BNP to take part in elections, and sought help from India to keep his government in power.

While the foreign ministry welcomes the US' threat of visa bans against people "responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the democratic election process in Bangladesh," Food Minister Sadhan Chandra Majumder termed the new visa policy a shame on the 170 million people of the country. His hurt feelings, however, are not shared by his party's General Secretary Obaidul Quader, who has been glossing over the threat by portraying it as a serious blow to the opposition BNP's demand for a poll-time caretaker government and a deterrent to the election boycott movement. A functionary of the ruling party, reportedly, has already written to Secretary Blinken with a hoard of proof, including video clips, of alleged campaigns against peaceful elections spearheaded by the BNP.

These contradictory statements from within the government, perhaps, reflect how rattling the US threat has become. Since the decision was communicated to the government almost three weeks before it was made public by Secretary Blinken, a coordinated and well-thought-out response was expected. Instead, the ruling party and the government do not yet appear to have fully realised its implications and scope.

Doesn't the issuance of a pre-emptive warning itself bear proof that the threat-issuing foreign power does not have confidence in our state institutions' ability to ensure a democratic election process?

If we recall the days after the US imposed sanctions against the Rapid Action Battalion (Rab) and a handful of its commanding officers, including two successive chiefs, we saw a sense of unreal hope that the unit was a victim of a mistaken act and soon they would be able to convince Washington to realise its mistake. Some of the leading intellectuals aligned with the ruling party made misleading arguments, too. Brushing aside US concerns about the worsening human rights situation in Bangladesh, they argued that the sanctions must have been the result of opposition lobbying as the US had apparently applauded Rab's role in curbing terrorism earlier. Their suggestions put emphasis on increased counter-lobbying, instead of focusing on improving the country's human rights situation.

If those spinmeisters were correct, then Bangladesh would have gotten back the GSP for its garment product exports to the US years ago, and the sanctions against Rab would have ended months ago. There's little doubt that much of a peaceful, free, and fair election depends on the state machineries' neutral and honest service according to the law. Doesn't the issuance of a pre-emptive warning itself bear proof that the threat-issuing foreign power does not have confidence in our state institutions' ability to ensure a democratic election process?

There's no denying that the opposition, too, can disrupt an electoral process. But that is not at the level of a party in power, as the administration very often sides with the latter. Denying political rights, and intimidating and harassing opponents in countries like ours are more likely to be the traits of the governing party.

Though the US does not reveal the identities of those who have been refused visas for privacy reasons, there are plenty of symptoms that make drawing conclusions easier. Nicaragua and Uganda can be cited as examples. In the case of Nicaragua, the post-election announcement of hundreds of visa bans had references of judges and officials. As for Uganda, the US termed the election neither fair nor free, and noted that the "opposition candidates were routinely harassed, arrested, and held illegally without charge. Ugandan security forces were responsible for the deaths and injuries of dozens of innocent bystanders and opposition supporters." I couldn't find any example that allows a contrasting conclusion.

Misleading analyses can help propagate a narrative for immediate damage control, but are not helpful to overcome the real crisis. In our case, it is the loss of credibility and trust in the existing system and institutions for restoring a functioning democracy and rule of law. Suffering from denial syndrome will not help restore a credible election process. It's time to initiate dialogue with urgency and sincerity for a truly inclusive, free, and fair election, and make the nation dust off the shame of being threatened.

Kamal Ahmed is an independent journalist. His Twitter handle is @ahmedka1

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments