Navigating a world without Indigenous representation

In Class 6, my class read about my community in a social science book. It was just an introduction of our food habits and where we lived. There was no mention of our distinct social, economic or political systems unique to Indigenous identity. Truth was, I could see the non-Indigenous world only, but not myself.

Once a co-worker told me I belonged to the common area of all overlapping circles that represented minorities based on gender, religion and race. He didn't hint at my high vulnerability level, rather envied that I enjoyed all the "minority privileges" that would help my application get accepted to foreign programmes. He made me feel guilty.

Like me, many Indigenous people see themselves only through others' eyes.

Article 9 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that Indigenous people have the right to belong to an Indigenous community in accordance with the concerned traditions and customs. No discrimination of any kind may arise from the exercise of such a right. Yet, a lack of representation is intertwined with ignorance towards Indigenous history and identity. We are called immigrants whereas we are the first inhabitants to our region. We are debated by groups, telling us who we really are and how our food habits should change. It's humiliating!

When a child is disrespected for who she is, she will reject her home and culture. It's easier to believe what she is shown than dig into her unpreserved ethnic history. Confidence is not the obvious outcome, rather the exception. Beauty images are served that look nothing like us. We grow up being called chinku, ridiculed for our bocha naak. Our food habits are labelled unhygienic. Where is the culture survival guide for Indigenous children?

The isolating feeling persists in a life-long cycle. People around us are amazed by Kaptai Lake's beauty, turning a blind eye to the displacement of thousands in 1960. Our friends plan trips to Sajek and we cannot help but tear up because of the food crisis in the region. When we are frustrated, we are called antagonists. It's as if only we get to see that the hills are bloody, and it is lonely because no one else does.

One might reach a conclusion that Indigenous peoples are good at sports. For example, it is an exciting time when Bangladesh is facing India in the SAFF U-20 final where Indigenous players like Sojol Tripura are representing the country. Last year, Bangladesh's U-19 women's team clinched the SAFF U-19 Women's Championship after defeating India 1-0. In the 80th minute, right-back Indigenous player Anai Mogini's long range cross outside the D-Box led to Bangladesh scoring the winning goal. This is when it is important to reflect: Do we have Indigenous representation in decision-making for the career of these Indigenous players? How can we make sports more accessible for Indigenous aspirants from the remotest corners?

Other professions commonly associated with Indigenous communities are tied with access and perceptions. At beauty salons, I admire the sense of sisterhood among Garo salon workers chatting in their mother tongue when attending to customers. Indigenous waitresses or store staff, coming to the cities to earn a livelihood, are exemplary for the sheer determination to adapt to a completely different cultural setting. As much as these professions have given them financial freedom, it can become dangerous if their possibilities are limited to these. Employers may deem ethnic candidates only fit for blue-collar positions, creating a glass ceiling.

A lack of representation in leadership makes the positions appear out of reach for them. Imagine yourself in their place. With no precedents set, you don't know what's right. The formula for a reality like yours has not been cracked yet. Securing a spot requires additional creativity and courage. Creativity, because you are not served images of people like you, so you have to create them in your head. "How do I pass the entrance exam when I am not well-versed in Bangla or English?" Courage, because you don't even know if you are actually welcome. "Are my surroundings capable of imagining what an Indigenous professor looks like?"

Even when you make it, you don't feel you belong. You tell yourself, "I have to be grateful for a seat at the table." You have to work extra hard to prove you are worthy. Much of this conditioning can lead one to mainstream themselves for acceptance. When culinary expert Arpon Changma established CHT Express that specialises in Chakma food items, people came to his restaurant and, upon seeing ethnic faces, left. Yet, today, the chef of BBQ Express is pushing the culinary envelope unifying different cultures: the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Texas and Dhaka.

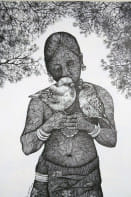

Representing culture through work has been long done by artist Kanak Chanpa Chakma. Her subject of women represents the point at which Chanpa's artistry converges with her activism. In her art, chores like carrying water and cultivating are testament to the extraordinary everyday strength of the Indigenous women she depicts. Her paintings are often accompanied by a mix of red, yellow and blue. While the colours depict hope and cultural heritage, Kanak doesn't shy away from using red to depict the pain and violence that has been inflicted upon Indigenous communities.

Kanak recognises the immense work it takes for an Indigenous artist to gain a foothold in the country's art scene. In an effort to create a ripple effect, she founded Ethnic Artists' Forum, mentoring a young group of Indigenous artists. I visited "The colours of youth," which was the first ever art exhibition by Indigenous artists for me. It was the first time I saw my community's reflection in art: Indigenous motherhood, the intertwining existence of nature and ethnic communities. Do you remember the first time you felt seen?

Representation aids in the creation and validation of the identity of the represented. It is the seemingly unimportant moments where people see someone who looks like them in the media or workplace, and are subconsciously influenced by this experience. Indigenous content creators like Sukanan Chakma and Payel Tripura are claiming their place in fashion and entertainment in the digital world. Their presence in trendy TikTok videos allows me to see our Indigenous culture as a part of the evolving digital landscape, too.

Such content fights misrepresentation. Storylines with a Bangalee girl playing the role of an Indigenous young woman falling in love with the settlers reinforce the Bangalee fantasy towards Indigenous women. Authentic Indigenous representation in media is an antithesis to Nuhash Humayun's advert for Tecno, where an Indigenous boy is given a Bangalee name, portrayed to offer namaz, and where Bangalee settlers live in bamboo-framed homes of the ethnic communities.

Navigating the world as an Indigenous person is like walking between two different worlds. You belong to neither. You are too foreign for the outside world, yet you are stripped off your identity when you want to make your place. Seeking representation is asking for fairness, to extend beyond a fantastical realm. How else do we promulgate the truth of our Indigeneity?

Myat Moe Khaing is a marketing strategist at a multinational company, who takes an interest in Indigenous and gender politics.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments