No country for women and girls

It was a small news item on The Daily Star's September 7 issue: a 19-year-old tourist was gang-raped at a tourist cottage in Cox's Bazar. One suspect is already in police custody, and police are trying to arrest the others. According to another report on the same incident, the two girls were brought from Dhaka to Cox's Bazar to participate in a dance programme. Rajan Cottage, where the assault took place, was the site for similar violent sexual assaults in December 2021. On its face, the incident does not warrant a comprehensive analysis, for it does not seem "exceptional," mostly because of how normalised such violence has become in our daily lives. At least two similar incidents, both in Cox's Bazar, gripped the nation's attention at the end of the year 2021. The first was when a gang of young men kidnapped a couple and their child and eventually raped the young woman repeatedly. The other incident was when a college student was picked up, raped, and kept hostage for three days. In response, the Cox's Bazar deputy commissioner decided to create a 600-feet safety zone for women and girls, only to go back on the decision within 10 hours amid furious reactions from the citizenry.

All three incidents and the since-abandoned "safety zone" plan help build a complex narrative of women's mobility rights, the conceptual slippage between women's safety and protection, and the culture of impunity that encircles sexual assault against women and girls.

The Bangladesh Constitution ensures its citizens' mobility rights and freedom of movement as a fundamental right. According to the Act No 36 of the 1972 constitution, "Subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the public interest, every citizen shall have the right to move freely throughout Bangladesh, to reside and settle in any place therein and to leave and re-enter Bangladesh." At its core, citizenship is a marker of one's identity; it confirms an individual's membership in a political community. In theory, citizenship entitles all citizens equal rights and such rights ought to be equally distributed; in practice, however, citizenship rights are often awarded and carried out in a gradational scale where the poor, the marginalised, the women, and the minority often experience difficulty accessing them. Citizenship, thus, is also a category of differentiation – it operates on the principles of both inclusion and exclusion.

Freedom of movement is not merely limited to movement for the sake of leisurely purposes – even though that, too, is an important need a woman may have – but that freedom extends to women's participation in economics, education, and indeed social development.

The repeated nature of the incidents compels us to rethink the construct of citizenship along gendered lines. In her essay for the Economic and Political Weekly, Anurekha Chari argues, "Women's oppression is exemplified in the way women experience citizenship rights." Gendered citizenship as a concept must negotiate the binaries between private and public, cultural and political, and individual and collective. In other words, when the constant threat of violence acts as a barrier to women's economic, social and developmental rights, such threat to violence delimits women's exercise of citizenship.

Take, for instance, the Narsingdi railway station incident from 2022, and the High Court bench's placement of blame on the victim. The bench asking "whether anyone wearing such a dress can go to the railway station in a civilised country" makes explicit the link between mobility and restriction – in this case both for clothes as well as movement. The ruling implied that the woman was wrong on at least two accounts: that she wore such an "uncivilised" outfit and that she went to the railway station wearing such an outfit. Such rulings made at such a high level of our legal system reaffirms the notion that staying immobile, not leaving homes, and not travelling will ensure women's safety.

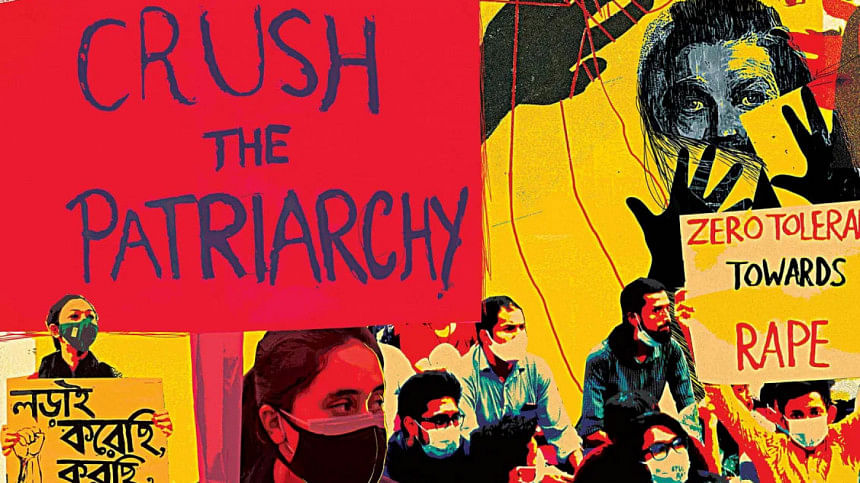

But what indeed is safety? When thousands of women face assault and violence in their own homes, what codes of safety and protection can ensure women's right to, well, exist? Hence, in recent times, the call for feminist action across the globe – and here, too – has largely been about protesting the restrictions put on women's freedom of movement. The focus now is on their right to exist in spaces and places that historically and culturally have restricted their entry into them.

The latest incident in Cox's Bazar, had it produced a strong response in the newswire (it likely did not because we have become desensitised to the trauma of such events), would have had two conflicting narrative responses. The narrative steadfastly committed to blaming the victim of sexual violence would question why the women travelled alone, what clothes they were wearing, what being a "dancer" says about their "character," etc. The other narrative would be intent on placing even greater restrictions on women in order to ensure their safety.

But here's the truth that many still feel uncomfortable to acknowledge or accept: in the name of ensuring safety, women's freedom to move – one of their fundamental rights as a citizen of this country – is being curtailed. "Protecting" women and girls and not ensuring their freedom disables them from being full and equal members of society. The country's leading higher education institutions, for instance, especially public universities with student halls, tend to impose disproportionately high restrictions on female students' movements. Students living in girls' hostels or all-female apartments face similar constraints. Simply put, adopting only preventative mechanisms ensures that women and girls remain bound by their gender.

Freedom of movement is not merely limited to movement for the sake of leisurely purposes – even though that, too, is an important need a woman may have – but that freedom extends to women's participation in economics, education, and indeed social development. Consider, for example, the number of cases we know of where women did not leave their home for higher studies, did not accept a job relocation or could not expand their business in a different region of the country. From infrastructure to housing to livelihood, restricting women's right to movement fundamentally impedes their citizenship rights.

Ultimately, sexual violence against women and girls cannot go on unchecked, nor can we attempt to "protect" women in the name of safety and keep them confined to "safe spaces." We must, without fail, take into consideration the nexus between violence as a barrier for women's emancipatory participation in public life and the exercise of their rights as the citizens of the state.

Dr Nazia Manzoor is assistant professor at the Department of English and Modern Languages in North South University (NSU).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments