One more vote, one vote fewer: Why people will and won't go to polls

Even in an election without choice, the 'will they' or 'won't they' question still applies to voters. So, The Daily Star asked two young voters to explain their decisions as the 12th parliamentary election rolls out. Views expressed below are the authors' own.

Why I will (attempt to) vote

Before you judge me (for all the rightful reasons), I'd like to add a disclaimer: I am in no way being preachy about why voting is "indispensable" for the 12th parliamentary election taking place today. To be quite honest, I don't see any reason why I should convince anyone to vote, given what's been going on for the last few months surrounding this not-much-anticipated event. Instead, let me tell you why I decided to show up at the polling centre early in the morning, sacrificing a winter morning's sleep.

In the last few months, any remaining possibilities of a contest, fair or not, have gradually eroded. In most cases, it's the ruling party, candidates endorsed by it, and its allies who are contesting against each other. The ruling party made it absolutely clear with its actions that a free, fair, and participatory election is not plausible as it holds on to power adamantly, leaving no avenue for a real opposition to contest against them by imprisoning top BNP leaders and inflicting violence on their protest rallies.

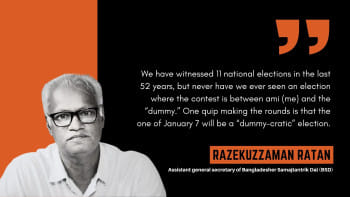

The current regime has made it almost impossible for people to talk about the absurdity surrounding the national polls as well. In the last five years, there have been continuous attempts to muzzle free speech using the Digital Security Act, 2018. There is no tong adda discussing the polls, a quintessential practice in Bangladesh's election season, due to a looming fear of persecution. For most of the country's electoral history, the losing parties have accused polls of being "unfair" or "blatantly rigged." In my opinion, the most unique characteristic of this election is that, without any semblance of competition, nothing remains to be rigged in the first place. It's the ruling party versus the ruling party. No matter whom we vote for, there remains no doubt about who will be forming the government. A stage has been set, a script has been written, and the actors and directors are all aware of the ending.

Under such circumstances, mass boycotting and compelling those in power to rethink the election would be the most obvious path to take. However, a boycott campaign needs months of mobilisation, media attention, and the involvement of the masses for it to actually stand as a statement. The opposition parties did too little and too late to mobilise a mass boycott campaign that would have actually resonated with the people. Most people who were interested in having a conversation with me about why they would or would not vote said they did not really have a candidate to vote for. "It's AL vs AL, really," a friend told me. "Why waste a day-off on this?" This reflects the sentiment of the majority when it comes to the question of whether or not to visit the poll centres.

But is this enough to make a collective statement? I think not. In our experience of surviving in this chaotic "democracy," we, of all people, should know better that numbers can always be made up even if voter turnout is really low. Anything we do or don't do will be used against our own interests. Don't get me wrong; I do understand why people say that showing up to vote will not make a difference, and might just legitimise a "dummy" and farcical election. But we also need to realise that those in power are not waiting for our actions to legitimise their stance. They are well-prepared to conduct yet another hostile takeover while making it look as much like a democratic process as they can.

If you don't decide to vote, tell us why. If you do vote, talk about the things, particularly the dilemmas, that you faced. Keep the conversation alive.

For a country that has gone through multiple bouts of autocratic and military rule, democracy and the right to vote are almost sacred, even if they have turned into jokes of late. Democracy, in my humble opinion, needs a lot of conversations for it to stay alive in a country like ours. So when I decided to show up at the polling centre, it was for the sake of keeping a conversation alive. To talk to people as a fellow citizen about why they decided to show up. Not every voter wishes to vote for the ruling party's candidate. Yet, they will. What drives them during this darkest time for democracy? What hopes and aspirations are they left with for the country? How can we, as a people, achieve these together?

I will not ask you to show up at the voting centres. I have no right or authority or moral high ground to convince you to do that. All I can ask you to do is this: whatever you do, make a statement. If you don't decide to vote, tell us why. If you do vote, talk about the things, particularly the dilemmas, that you faced. Keep the conversation alive. Don't let anyone forget about all the things that are wrong in this so-called democratic process. The tong adda might be where we can restart the conversation. Showing up to the polling booth would be my first step towards that. You have to decide on yours. Don't let this be just another day-off from work or school.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is a writer and journalist.

***

Why I won't vote

"Does my vote matter?" Since the year I became eligible to vote, 2014, I have had this exact thought in the days leading up to national elections. That year, the answer was "no." Five years later, it was still the same.

This election, I ask again: does my vote matter? The answer, again, is a big "no."

Whatever is happening in the name of democracy this time can be described with one specific term: election engineering. Unlike the polls of 2014 and 2018—which were either largely uncontested or events of large-scale vote-rigging, effectively disenfranchising citizens—the ruling party is bent on giving voters, and a watchful world, the illusion of competition and participation. But in this quest, it has ironically demonstrated the extent to which it can go to ensure that an election is anything but free and fair.

The crackdown on BNP, right after its October 28 rally, ensured that the party was out of the picture. With its leaders behind bars, BNP was left in ruins, and in the absence of an actual opposition, AL decided to make up competitors. While the ruling party's insecure allies were busy negotiating for seats for themselves, AL paved the way for its party members to run as "independent" candidates, many of whom are just dummy contenders. And let's not forget the contesting parties that exist only on paper.

So, what difference will my vote make? In what world can this be called an election? No matter which ballot I put in the box, I and everyone else will be voting for the same party—Awami League.

As a citizen, I keep racking my brain, questioning why we are spending more than Tk 2,000 crore on this glorified theatre play, when our people are reeling from a protracted economic crisis, many clawing for bags of rice and lentils behind the TCB's trucks. I ask myself: if a party truly wants to serve the people, would it need to go to such lengths to stay in power?

With each passing year, my naivety disintegrates, bit by bit.

In 2018, I used to think my voice could change things. But the government's response to the Road Safety Movement that year proved that I'm more of a cog in the machine. The battered bodies of students meant nothing to the regime, as evidenced by the rising number of road crashes each year: 4,891 in 2020, 5,629 in 2021, and 6,749 in 2022.

And entering journalism drilled in me a sense of disillusionment, with statistic after statistic of this kind. Now, I'm just tired.

There are many more like me, who are weary of seeing the economy being crumbled by the hands of money-laundering oligarchs; of witnessing starving people taking shelter under flyovers and expressways; of dealing with endless violence; of having zero influence on the state of governance; and of seeing their all-empowering role as voters being reduced to five minutes of fame on election day.

Violence—meaningless, thoughtless violence—has always marred our elections, local or national. Whether it be assaulting opposition members or clashing with fellow partymen or the innumerable arson attacks on public transport, it's as if the polls are designed to incite this carnage. But let's pause and think: why must this charade take even a single life? Unlike fictitious pledges and voter turnouts, such lives, whether they be of political activists or average people, have meaning.

On Friday night, I felt helpless when I came across the photo of a man in a burning compartment of the Benapole Express. He had his arms hung over the window, his body still inside the train. That man, his family, and the other scarred/scared travellers had nothing to do with this farce of an election. And yet, they had to suffer this excruciatingly unjust fate.

Not a single political party in this country deserves my vote, because they are either malicious beyond description or too incompetent to be able to stop the prevailing madness. None of these parties will even remember the names of the victims of the Benapole Express attack; the election will go on as usual, while the "collateral damage" will keep racking up.

I'm tired. I don't want to see meaningless deaths, or people living in fear. I want things to change. I desperately want my vote to matter, and I dream of a day when it will. But today is not that day. Sensing this desperation and resignation, ruling party men reportedly have been urging, coercing, and even threatening voters to go to the polling centres. Social safety net benefits and basic services like birth registration have been put on the line. So, many have no choice but to participate in this hollow shell of an election—this cruel comedy.

However, as a relatively privileged member of society, I have a choice. Today, I can choose to not play one of the countless characters in this orchestrated performance. I can choose to resist the regime's grand plan of showing the world how participatory and legitimate this election is. And, by not voting, I can choose to call this election what it really is: a sham.

Shoaib Ahmed Sayam is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments