Online violence against women is real violence

The campaign for 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence this year encourages citizens to share the actions they are taking to create a world free from violence towards women. But what is being done about the online misogyny and violence encountered by gender justice activists, individuals, and organisations fighting for women's rights and creating awareness online? Do our laws, the state, and its citizens consider an action to be gender-based violence only when it results in physical harm, rape, sexual assault, murder, or something severe?

Every day, women of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds become victims of online harassment and abuse in the form of trolling, bullying, hacking, cyber pornography, etc. Although there is no nationally representative data on victims of online gender-based violence, according to Police Cyber Support for Women, 8,715 women reported being subjected to hacking, impersonation, and online sexual harassment from January to November 2022.

Although UN Women recognises technology-facilitated gender-based violence, Bangladeshi laws and law enforcement agencies have largely overlooked online gender-based violence by not recognising it as "violence" and not having proper legal remedies to counter it.

First of all, there are controversies and confusion among both lawyers and law enforcement agencies about which law—the Pornography Control Act 2012, Women and Children Repression Prevention Act 2000, or the much-debated Cyber Security Act (CSA) 2023—to use when dealing with cases of online gender-based violence. On one hand, the Pornography Control Act 2012 can be used in cases where the victim's sexually explicit photos or digitally manipulated images are shared online. However, online gender-based violence is not only limited to cyber pornography. Online trolling, bullying, and hate speech ranging from misogynistic comments to rape and death threats have the ability to devastate women's lives. Yet, no law directly addresses such violence.

One can argue that there are certain provisions related to the transmission and publication of offensive, false, threatening, and defamatory information in Sections 24, 25, 26, and 29 of the CSA, which have the potential to be used as a protective tool for women and children online. But to what extent these provisions will be effective remains a question, especially because they do not explicitly mention the protection of women, children, and minority populations. Victims of online gender-based violence are also confronted with the added burden of deciding whether to file a case at their nearby police station, the designated cybercrime unit of police, with Rab, or contact a lawyer to file a case directly at the court.

Secondly, lack of technical knowledge about cybersecurity leads to difficulties and delays in the implementation of legal actions. When victims lodge complaints, the police ask for the online link to the hate speech, threat, or pornographic content, which is sometimes difficult for victims to provide. The police sometimes ask for a physical crime scene location, name, and address of the perpetrator in order to file a case, but these crimes take place online and perpetrators are often unknown to the victims.

Finally, social norms and the stigma around gender-based violence play an integral role in hindering the pursuit of justice, as women have to face a myriad of uncomfortable questions—bordering on character assassination—while seeking justice for online gender-based violence.

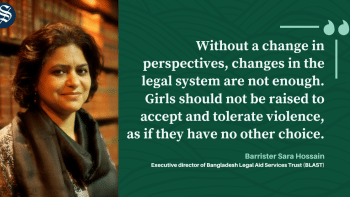

Despite the overall grim reality of online gender-based violence, a month and a half after the CSA was passed, six cases were filed by women in the Cyber Security Tribunal (against hacking and cyber harassment through the spread of manipulated images). Still, there is a long way to go if we want to protect women and gender justice activists from cyber abuse, which is fueled by decontextualised religious and cultural narratives of "ideal women'' who never vocalise the violation of their rights. According to BLAST's review of the recent CSA, the defamation clause in Section 29 can exacerbate the malicious prosecution of women who voice their grievances, abuse, or harassment through online support groups. Without protective mechanisms in place, laws on defamation—and even the CSA—can be a double-edged sword for victims who are speaking out about their sexual abuse.

Immediate action in response to reports of online gender-based violence is imperative to ensure the safety and dignity of women and gender justice activists online. Coordination between law enforcement agencies and cybercrime helplines or NGOs working for women's safety in the digital space is of vital importance. The pleas of women victims of cybercrimes must not be overlooked by the state as a minor "online nuisance." Online gender-based violence must be recognised as a serious form of violence.

Shamsad Navia Novelly is a research associate at the Brac Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) of Brac University.

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments