Oscars 2024: War won big, but the problem wasn’t the winners

For film industries, 2023 was undoubtedly a great year, making this year's Oscars the most anticipated since Parasite made history before the pandemic. In many ways, the Oscars is just a silly award show, but in the 96 years of its existence, it has become a global pop culture phenomenon. The two biggest blockbusters scoring nominations in major categories have revived the thrill of "good" movies and brought critics and moviegoers closer. The addition of hundreds of international voters since the #OscarsSoWhite controversy also saw a historic three foreign films nominated in the Best Picture category, extending the base for excellence in film-making beyond Hollywood.

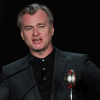

Despite the diversity, Oppenheimer, an abstract, expansive film about J Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist who made the atomic bomb, created by celebrated director Christopher Nolan, bagged seven wins—the same as last year's Best Picture winner, Everything Everywhere All At Once. Nolan's film deals with a heavy, debatable theme—from quantum physics to war crimes of dropping the first and only nuclear bombs in warfare—yet it's been watched by a lot of people, and a lot of people have liked the cinematic experience that leaves one with disturbing thoughts after the credits roll. No matter what one thinks of Nolan, or his wife Emma Thomas, who was the producer, it's hard to argue "objectively" that his direction was not excellent. It is equally difficult to criticise the whole film as just an Oscar-bait "biopic," the same way it is too simplistic to reduce the film to a mere tale of "White guilt"—another common criticism of the first box office blockbuster in decades to have won the Best Picture category. Oppenheimer might be about the guilt of a White scientist, and that, too, is significant. Those in the West who are creating weapons today can learn something from it.

Nolan's choice to omit the Japanese people's perspective is contentious, but Oppenheimer paints horrors and ruins of war through sounds provoking the audience's sensory neurons, much like The Zone of Interest, another World War II movie which won the Best International Film. Both films delve into the perspectives of war from the perpetrators' sides; they are not asking viewers to empathise, but offering imagery, decisions, stories to see "how" the dehumanisation unfolds. Those with blood on their hands, the executives in the corporations making the weapons, are human beings who live among us. Not all political entities and military members who make and execute the decision to kill are born with psychopathic behavioural disorders. Both films explore how ordinary people, or extraordinarily brilliant people, find themselves in the monster seat.

Before the lead actor award was announced in this year's ceremony, Academy Award winner Ben Kingsley aptly described Cillian Murphy's performance in Oppenheimer to have encompassed humanity, though his character created something so inhuman. The significance of Oppenheimer lies in the fact that we get to see the dreadful possibilities of the human mind: how scientific curiosity and a quest for achievement venture into catastrophic creations. These elements of the Best Picture winner are very relevant today: the arms race in the film between the US and the Soviets parallels the AI race in today's Cold War era, and more frighteningly, we have seen the fruits of technological advancement deployed to kill Gazans.

The Best Picture, unlike other categories, is decided on a preferential ballot system. As Oppenheimer had won the top awards at BAFTA, SAG, Golden Globes and Critics— all big-scale Oscar precursors— it was a shoo-in for those of us following the buzz. Any other film winning instead of Oppenheimer would've been a surprise.

The Zone of Interest and Oppenheimer make the audience question and introspect how war crimes occur through two different stories. Art should not have to spoon-feed moral messages to be considered meaningful. In a year of great movies—but also a year marked by the onslaught of another war in the Middle East and genocide of Palestinians, while the Russia-Ukraine war rages on and the US-China Cold War intensifies—the Academy awarded Oppenheimer, The Zone of Interest, and 20 Days in Mariupol for Best Documentary Feature. The new kind of favoured story-telling—there's always a phase every few years, from thrilling social satires like Get Out and Parasite to awareness-raising movies about marginalised groups such as Moonlight and CODA—is challenging narratives of mass human conflict, and flipping the narratives of cartoonish evil villains for a better understanding of war itself.

The Zone of Interest, an eerie take on the unbothered daily life of a German commander's family sharing a wall with Auschwitz camp is not another victimising Holocaust movie to jolt sympathy. The Nazi commander's children splash water in the pool, while screams of the Jewish children being industrially persecuted on the other side of the wall reverberate the ghastliness of the Holocaust. With little dialogue, and deleting the visuals of the horror but playing its sounds over the bucolic bliss of a Nazi family, the film sermons the horrid extent of normalising dehumanisation. Though it predates the ongoing genocide in Gaza, it answers the burning question we ask regarding the Israeli perpetrators: how do they sleep at night? Normally, the film shows, which makes it all the more nauseating.

The director, Jonathan Glazer, who is Jewish himself, was the only one in the ceremony to speak about Gaza. He said, "All our choices were made to reflect and confront us in the present, not say, 'Look what they did then,' rather 'Look what we do now.'" He went on to condemn the usage of Holocaust by an "occupation," though one could sense self-censorship as he read his speech from a piece of paper, his hands shaking visibly. The only other one who spoke of the dark content being rewarded was Cillian Murphy—who made history as the first Irish-born actor to win an Oscar. He said, "We live in Oppenheimer's world" (an ode to the last line of the deadly chain reaction his character started), and ended his short speech dedicating his award to the "peacemakers." The Academy Award ceremony in Dolby Theatre was a lot more censored than previous years, perhaps purposely and pre-emptively to avoid controversies.

We love hating the Oscars after the curtains close and debating whether those who won deserved the prestigious honour. The debates that follow are always subjective as the notion of a best performance itself is such. This year's outcome was mostly chalk other than the tight Best Actress race, where Emma Stone bagged her second Oscar win over Lily Gladstone, the first Native American actress to have been nominated. But it's hard to criticise this too, if you see Emma Stone's all-time great performance—with far more screen time than Gladstone—in Poor Things. Stone's win doesn't feel right—even to her, judging by the actress's own reactions to the announcement of her name—but it doesn't feel wrong either.

The Best Picture, unlike other categories, is decided on a preferential ballot system. As Oppenheimer had won the top awards at BAFTA, SAG, Golden Globes and Critics— all big-scale Oscar precursors— it was a shoo-in for those of us following the buzz. Any other film winning instead of Oppenheimer would've been a surprise. (On a side note, I would've personally loved to see Anatomy of a Fall, an unusually thought-provoking masterpiece on relationships, violence and murder, grab the title.)

The problem with this year's Oscars was not the subjective, voter-based awards itself (though Killers of the Flower Moon, a brave Martin Scorsese production about the annihilation of Native Americans, perhaps could've gotten at least some recognition). There was a general aura of restraint and formality in the ceremony, which seems to have been anticipated and countered with spotlighting the entertainment aspects of cinema—piggybacking on the fun performances of Ryan Gosling and the catnip traditions for old-school Oscar lovers, having former Academy Award-winning actors laud each nominee in the acting categories before announcing the winners.

The main issue with the grandest night in Hollywood was rather that despite thought-provoking war films winning major categories at a time when horrors unfold in the world, the night was filled with stars thanking their publicists and kids and steering a bit too clear from pressing political issues. The only person who spoke of the most pressing issue regarding the persecution of Palestinians by Israel was a Jewish director, who made a movie about the persecution of Jews. Perhaps that is a lasting moment from the show this year—the rest of the circle of cinema elites that has used its work, and the recognition of its work to speak up about the wrong in the world suddenly lost its vocal chords. Previously, especially during the Trump era, the podium of award shows was rampant with the Brad Pitt type of sarcastic political jokes, or Joaquin Phoenix's lengthy moral signalling about the environment, or Frances McDormand's vivacious feminism. The billion-dollar industry's political activism was tragically missing in a year its presence was most needed.

Ramisa Rob is a journalist at The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments