Our brains react differently to digital and printed text. What does this mean for readers?

We see literacy as so fundamental that we categorise history and pre-history based on the invention of writing. Socrates, in Phaedrus, states his suspicion of writing because it fixes words on the page and cannot reply to questions posed to it. Yet, this ability to affix meaning to something independent of any situation is the power source of literacy, because it allows us to communicate and retain information across time and space. Literacy allows people to build upon what has gone before and not have to start from scratch each time.

Researchers of literacy now argue that while reading is a more recently discovered activity, it has also impacted our evolution by shaping our brains.

In her book, Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, Maryanne Wolf – a cognitive neuroscientist and literacy expert – explains that the advent of reading and writing caused the human brain to rewire itself in ways that it would not have done otherwise. The brain on literacy is compositionally different than the brain in oral cultures (this can be a controversial but also logically coherent topic if one starts with the view that the developing brain is like moldable plastic and the neurological connections we make at an early age often create the framework that undergirds a lot of what we do with our brains later in life.)

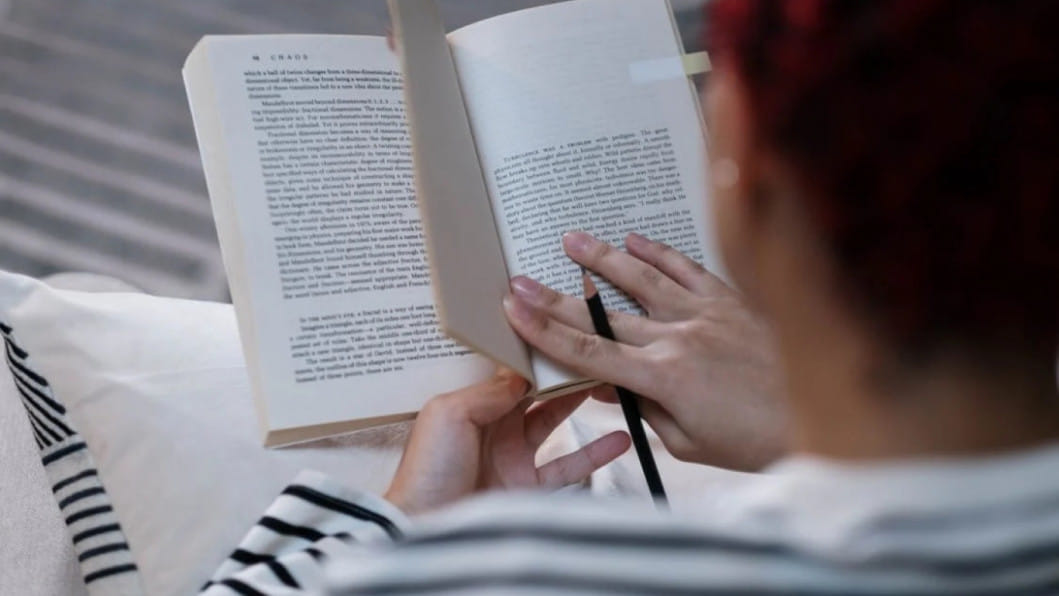

In her studies of reading using MRI machines, Wolf found that reading is a complex cognitive process that engages different areas of the brain. It is not a passive activity, but rather an active and dynamic process that requires making connections between different modes of information in order to create meaning. Experiencing reading on the page wires the brain to make use of the visual cortex (which makes sense of the words and letters we are seeing); the parietal lobe (which involves spatial attention and the ability to integrate information from different sources); and the frontal lobe (which is involved in decision-making and problem-solving).

Additionally, the brain's language centres, such as the left inferior frontal gyrus and the left superior temporal gyrus, are also activated when we read. The brain of a person who did not read from an early age would not have a framework particularly strong when it comes to such connections.

We generally use the same parts of the brain no matter the medium, with one crucial exception. And therein lies the rub.

Reading off a screen relies more on the visual cortex and reading off the page relies more on the language centres. When we read a page, our eyes move in a series of short, rapid movements called saccades, followed by a brief pause during which the brain processes the information. This process is called the fixation-regression cycle, which allows us to comprehend and retain information efficiently, and it takes place in our brain's language centres. It also means that, during this process, we translate the information into symbols and mediate it through our imagination, or the grounds of what John Keats called our "negative capability."

In contrast, when we read from a screen, our eyes scan the text in a more continuous motion, without pausing to process. This can lead to a decrease in comprehension and retention, as the brain is not given enough time to fully process the information. The deluge of visual input means our brains opt to bypass our language centres. Consequently, the process neither fosters thinking nor develops concentration and focus. Screens also tend to have a higher level of visual noise and distractions, such as ads and pop-ups, which can hinder our ability to focus and comprehend what we are reading. We might open a browser tab and then fall into a YouTube rabbit hole that confounds our thoughts with tangents. Lengthy exposure to the bright blue light of the screen also suppresses the production of melatonin, a hormone which regulates our brain's ability to relax. These continuous cascades of stimuli create a type of informational sugar rush, and we end up crashing rather than feeling nourished.

This does not mean that we can abandon digital reading and become Luddites clinging to our leather-bound manuscripts. The scale of information and literacy activities in the world is too exigent and demands too much of us to engage with it only through pen and paper. Rather, what we must now do is create a diet for ourselves as we manage our reading activities. Researchers and well-wishers of reading argue that we need to think about reading literature in printed books as we might about eating our vegetables – to balance out our literacy diets.

This is because literature on the page can help develop our focus and support our well-being. It helps us quieten our minds and escape the distractions buffeting us on all sides – mostly from our screens. Our engagement with the characters and the mediation of their representation through our imagination aids the development of our sense of empathy and emotional intelligence. We can grow to become more compassionate of others as we learn to think like them or see through their perspectives and words.

Finally, we learn to think more deeply through our reading activities, and this keeps us engaged on one topic, leading to a fuller and more fulfilled understanding.

Reading on screens is the primary way many of us will engage in literacy now. But we have to think about the medium as a message and develop a balanced diet in terms of how we read, if we are to retain the benefits of each. Reading on the screen is basic, but it cannot replace the cognitive and emotional benefits of reading on the page. As Wolf states, "The reading brain evolved to process words on a page, not on a screen, and our brains require a different kind of cognitive effort to read on screens."

It is important to maintain a balance between the two forms of reading and to prioritise deep, focused reading on the page (particularly when it comes to literature) for optimal comprehension, retention, and personal growth.

Shakil Rabbi is an assistant professor at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. He studies how languages and writing shape our social lives. Reach him at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments