Poison Tree of Partition

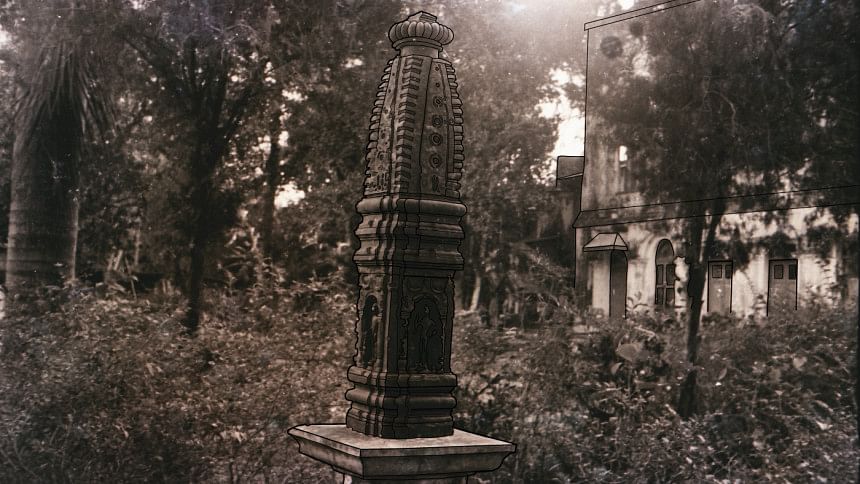

In 1953, my grandfather Maulvi Emdad Ali made a point to tell visitors to our Rankin Street home that it was not acquired through a "distress sale." A small dhvaja-stambha structure in the garden marked the home's pre-1947 provenance as a Hindu household. There was a residual stigma for new Muslim elites of East Pakistan about gaining property through the despair of departing Hindus. Our family patriarch wanted to mark himself as a fair purchaser of property—hence his additional references to having a British Indian Civil Service job before 1947.

Partition literature, from Toba Tek Singh (Saadat Hasan Manto, 1955) to Vatan Aur Desh (Yashpal Singh, 1960) to Kalo Borof (Mahmudul Haque, 1977), has circumnavigated dramatic changes in family fortunes during rupture and collapse (Sayeed Ferdous, 2022). In our encircled geography of intense land scarcity, it has been the property under your neighbour's feet, not the rituals in their temples or mosques, that have been the target of sudden acquisition. Riots, intimidating people into crossing borders or going into hiding were the first steps in this process of land acquisition.

The Government of East Pakistan, after 1947, needed a set of laws to acquire property for accommodation of new government servants and setting up offices. "Requisition of Property Act" (Act XIII of 1948) gave the right to take over property "needful for purposes of the state." This flowed into the "East Bengal Evacuees Act" (1951). In 1964, new riots after the Hazrat Bal incident in Kashmir led to the "East Pakistan Disturbed Persons Rehabilitation Ordinance" (1964). This new regulation restricted the transfer of "immovable property of minority community" without permission of the authorities. This meant that any Bengali Hindu wishing to leave East Bengal for any reason would now face barriers to even the lawful sale of their property.

The 1965 Indo-Pak war ended after 17 days and left behind the poisonous "Enemy Property Order" (1965). This was matched by a reciprocal "Enemy Property Act" (1968) in India. Demonstrating a civilian-military joint project to continue expropriating land, after the pan-Pakistan uprisings of 1969 led to the lifting of military emergency, the government immediately passed the "Enemy Property (Continuance of Emergency Provisions) Ordinance" (1969). Again, following the 1971 liberation of Bangladesh, this law miraculously survived via the "Laws of Continuance Enforcement Order" (1971).

On December 17, 1971, a new enemy population was born, as the Urdu speakers of East Pakistan (former refugees and transplants from India and West Pakistan) were trapped into the geographically inaccurate "Bihari" category and "left behind" (Dina Siddiqi, 2013) by the new Pakistan state. The moment of independence that we commemorate was also accompanied by looting and occupation, this time of Urdu speakers' land (Seuty Sabur, 2020). In 1972, the "Bangladesh Vesting of Property and Assets Order" merged the abandoned property of those who had left for Pakistan with those who had left for India. This was further solidified in the "Vested and Non-Resident Property Act" of 1974. Thus, both Urdu speakers' and Hindu land could be targeted for takeover.

The saintly aura we invest in our people creates lethal blind spots. The desire to take by force from vulnerable populations exists in all people, and after rupture events, that is what stays in our memory as a collective stain, while the moments of courage and community get forgotten.

Back in 1965, the Pakistan state had also discovered another vulnerable population whose land could be used for the magic of "development"—the indigenous Adivasi people in southeast Bangladesh who depended on customary rights for land ownership. Supported by American engineering technology, the Kaptai Hydroelectric Dam was built in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, flooding Adivasi villages and the Chakma royal palace. The oral history of this event, a micro-scale "Nakba" for the Adivasi peoples, is recorded in Samari Chakma's Bor Porong (2018). The Adivasis saw their crisis as limited to the Pakistan state, but in 1972, they received a new system shock when the constitution of Bangladesh defined only "Bengalis" as the "people" of the nation. The first defiance of the new Bangladesh government was Manabendra Larma's remarks on the Parliament floor: "Under no definition or logic can a Chakma be a Bengali, or a Bengali be a Chakma" (his remarks also erased the many non-Chakma Adivasi peoples).

After 1975, the Chittagong Hill Tracts became the site of the Adivasi guerrilla war, led by the Shanti Bahini—met with force by the military and accompanied by Bengali settlers. The equations of 1971 were inverted when India allowed the Shanti Bahini to set up clandestine camps, repeating the Agartala scenario. The huge number of Adivasis who had crossed into India after 1965, and then again with dramatic force after 1976, was the Indian state's raison d'etre for interference, just as the tidal wave of Bengali refugees was in 1971. The occupation of non-majority populations' land has been a bipartisan, as well as a civilian-military project for 53 years, no matter what sweet cultural ceremonies are presented to visiting dignitaries. Even the popular slogan of "Tumi Ke? Ami Ke? Bangali, Bangali!" erases Adivasis and Urdu speakers, and privileges "the Bengali sense of victimhood" (Rahnuma Ahmed, 2010).

The saintly aura we invest in our people creates lethal blind spots. The desire to take by force from vulnerable populations exists in all people, and after rupture events, that is what stays in our memory as a collective stain, while the moments of courage and community get forgotten. The media fans the flames, but it is our denial of contradictory histories, and the continuance of unjust laws and practices, that creates the opportunity for hostile eyes. Bengali Hindus, Adivasi Paharis or plainland Indigenous dwellers, Urdu speakers, Ahmadiyyas, Shi'a—all vulnerable communities have faced our wrath, always twinned with a gimlet eye on their land. Underneath are laws with a seventy-five-year legacy, that facilitate "distress" transfer and theft of land. If India and Pakistan are Salman Rushdie's "Midnight's Children" (1981), Bangladesh emerged as what I call "Midnight's Third Child". Our independent nation-state has survived and grown despite setbacks and interference, but we are yet to escape the forever poison tree of 1947.

Naeem Mohaiemen is associate professor of Visual Arts at Columbia University, New York. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments