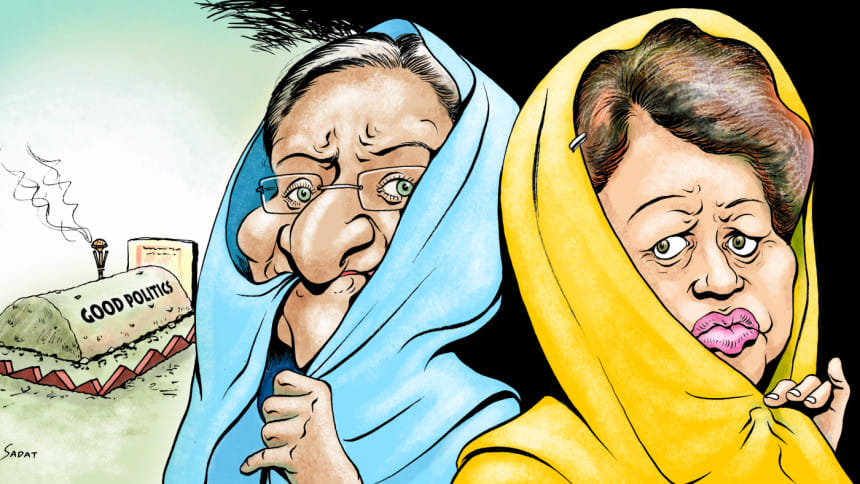

Political dialogues: The long road to nowhere

It is an established fact that elections bring about a gust of uncertainty for Bangladesh. Every election is preceded by a prolonged period of tension, when every discussion appears to swirl around the same concerns: "Will it be free, fair, and inclusive?" and "Will the parties – meaning the two major parties, Awami League and the BNP – hold talks to avert any uncertainty?"

With the national election coming up in less than a year, the situation is no different this time, either. Regarding discussions, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, also the president of the ruling Awami League, apparently ruled out any possibility. "Who will we hold a dialogue with? We held a dialogue [with them] before the 2018 election. What was the result? They did nothing except make the election questionable."

While the PM hinted that there would be no talks, the BNP went one step further.

The party's secretary general, Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir, said, "We will not engage in any talks with [the prime minister]. Why should we hold a dialogue with her when she does not keep her word? That's why we did not speak of dialogues for once."

If these two statements are to be taken as the last word from each side, then there is no possibility of a dialogue before the election scheduled for late December or early January 2024. The one inevitability, if there are no talks, is violence and destruction – for which both parties have been responsible when they were in the opposition.

Bangladesh's recent political history, since the 1990s, shows that these talks are doomed to fail no matter what. There have been instances where civil society members and foreign diplomats stepped in to have the two sides come to an understanding. But the talks were doomed mostly due to the uncompromising mentality of both parties.

The history of distrust between the two political parties and their leaders is nearly as old as the journey of democracy in Bangladesh. And it is still gradually widening. That's why we often see that whenever there is mention of talks, the opposition camp welcomes it, and the ruling party gives it a cold shoulder.

After the BNP government assumed office in 1991, the AL questioned the neutrality of arrangements by a political party following BNP's interference in the Magura by-polls of 1994. At that time, the Commonwealth secretary general, Ninian Stephen, came to Dhaka as a special envoy to break the political impasse, but that was not accepted by the ruling BNP.

So, the initiative fell flat on its face.

After that, a group of civil society members took an initiative to mediate talks between the two battling camps, but neither of them warmed to it. Noted economist Rehman Sobhan, journalist Foyez Ahmed, barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed, former Justice Kamal Uddin Hossain and former ambassador Fakhruddin Ahmed were among those who tried to mediate talks in 1996.

It was only after it was faced with a strong joint campaign from the Awami League, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, and some other political parties that the BNP government felt compelled to introduce a non-partisan interim government to oversee the national election.

In 2001, before the election, former US president Jimmy Carter tried to mediate a dialogue. But his initiative did not succeed, either.

Then in 2006, the historic talks between the two seconds-in-command of BNP and Awami League took place. BNP Secretary General Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan and Awami League General Secretary Abdul Jalil sat at a dialogue that went on for about three weeks on the issue of election-time government, but they could not reach an agreement. This uncertainty led to a very violent street clash and an eventual takeover by the military on January 11, 2007, which gave way to a state emergency.

We can also recall the UN assistant secretary general for political affairs Oscar Fernandez-Taranco's visit to Bangladesh to initiate talks. But that, too, did not see the light of the day, and instead resulted in BNP boycotting the election and AL forming the government with 153 lawmakers elected uncontested.

In an evolved democratic world, dialogue is regarded as an inevitable consequence of politics. Democracy and compromise are often two sides of the same coin. And a dialogue is key to reaching an agreement.

In the West, for instance, no matter how difficult an issue may seem, it is ultimately through dialogue that a decision is made. And public opinion is given the highest importance. Not only domestic issues, but international issues have also been settled through talks. Even far worse confrontations such as wars come to an end through talks.

The problem in Bangladesh is that Bangladeshi politicians consider compromise as a weakness and a sign of defeat. No one wants to "show weakness". Political parties must have a "winning attitude", they seem to believe. But do they also keep in mind the cost at which this is being achieved? Apparently not – and that is why talks fail and confrontation becomes imminent.

This has become a custom in our politics. Here, talks, elections, and democracy are measured through the party lens, not through the lens of the common people's interest or the country's welfare. And the responsibility of the failure of the talks typically rests on the shoulders of the ruling party, as the onus is upon them to offer something.

However, since there is no precedent of successful dialogue in Bangladesh, one might expect the inevitable – more tension and likely clash. It does not appear yet that the main opposition camp will prove to be as organised and strong in the field to compel the ruling Awami League into certain concessions. Then again, no one had thought the opposition camp would be able to pull off their divisional rallies with such huge public turnout, either. Uncertainty and apprehension should be in good measure for both camps. At least, not now.

Mohammad Al-Masum Molla is chief reporter at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments