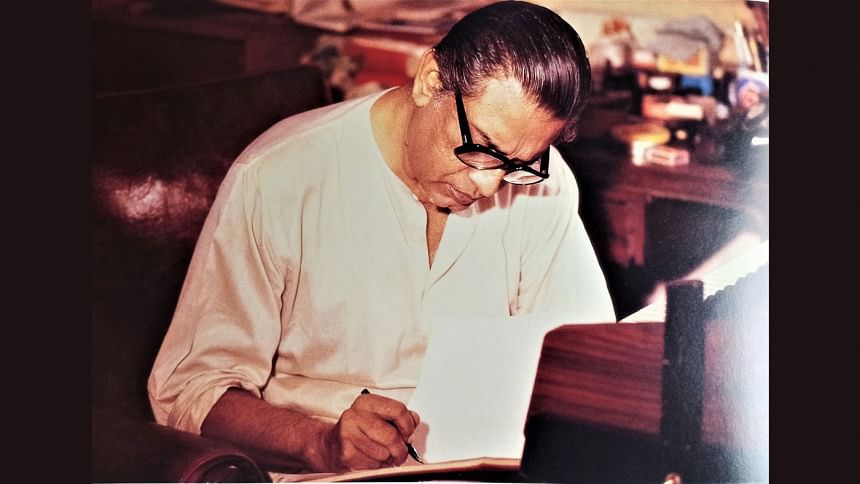

Power to the profundity and imagination: Timeless films of Satyajit Ray

From the 1920s to the early 1950s, several directors working within Hollywood—as well as filmmakers in former Soviet Union, France, Italy, Germany, and Japan—considered cinema not as a mere tool of entertainment but as a medium for creative expression. Filmmakers such as Charlie Chaplin, Sergei Eisenstein, Jean Renoir, Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Akira Kurosawa, and others deployed artistically innovative filmic devices to convey profound statements about the complexities of life. Some of the aesthetically satisfying films produced during this period were hailed as cinematic masterpieces. Films in India, however, prioritised cliched elements such as sentimental slush, ersatz emotion, theatricality, romantic tales, spectacle-like songs, and happy endings in these decades. Instead of making serious attempts at formal experimentation, Indian directors continued catering to the lowest common denominator audience.

In one of his articles written in 1948, Satyajit Ray said, "There has yet been no Indian film which could be acclaimed on all counts. Where other countries have achieved, we have only attempted and that too not always with honesty […] What the Indian cinema needs today is not more gloss, but more imagination, more integrity, and a more intelligent appreciation of the limitations of the medium." And in 1955, Satyajit Ray's maiden feature Pather Panchali brought the much-needed breakthrough in Indian cinema. The film went against the grain by incorporating location shooting, non-professional actors, a background score evocative of rural Bengal, and images depicting the scenic beauty of the countryside. Ray did not cast any superstars in the film. Instead, he chose Chunibala Devi, an octogenarian former actress for an important role.

Who would come to the movie theatre to see such an old lady, and a story that has no songs and romantic elements? Raising these questions, the producers showed no interest in financing Ray's film. But Ray was determined not to give in to the market demands. In order to continue the shooting of Pather Panchali, he even pawned his wife's jewellery and sold some rare books and classical music records from his personal collection. Later, the Chief Minister of West Bengal provided funds for the film from the money allocated for community development. Having seen the stills of Pather Panchali, one of the main directors of Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Monroe Wheeler, became very interested to hold the film's world premiere in MoMA. Would the affluent western audiences be interested to watch the plight and suffering of a poverty-stricken family based in a village in Bengal? The question ran through the mind of Ray when the film was sent to MoMA for its international debut. But soon he was informed that American film critics and audiences appreciated the film immensely. Shortly afterwards, the film became a box-office success in Kolkata. In 1956, Pather Panchali won a special jury award as the "Best Human Document" in the prestigious Cannes Film Festival. Upon its release in the US, the film ran for 36 weeks in the Fifth Avenue Playhouse in New York. Pather Panchali broke the record for the longest run in that movie theatre set by the famous German film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari.

As we remember Satyajit Ray on his birth centenary, it is important that we should encourage our budding filmmakers to find inspiration in the determination of this legendary Bengali filmmaker to use cinema as a means of self-expression and social responsibility. Still, we observe reluctance among the majority of our off-beat or alternative filmmakers to completely rid their films of light-hearted elements conventionally used to attract audiences. Having seen that our films rarely include socially significant subject matter, imaginative cinematic language, and social criticism, we cannot help wonder if our filmmakers are aware of the fact that films cannot make an impression unless they turn out to be the cinema of ideas and change. Strict censorship has often been regarded in our country as an obstacle to confronting burning problems in cinema. But, as Satyajit Ray imparted, censorial restrictions compel filmmakers to make statements subtly and obliquely, which can be interesting at times.

Under the guise of a fantasy film, for instance, Ray's Hirak Raajar Deshe provides scathing criticisms of despotic rule and the tendency of sycophants to flatter a powerful figure for personal gain. Showing a chamber used by the tyrannical ruler to brainwash the citizens, Ray makes the viewers aware of the contemporary way of instilling the dominant ideology in people via various social and cultural institutions to ensure social control. Lyricism, subtlety, and understatement are some of the key attributes of Ray's films. The lyrical approach combined with his success in arousing universal emotions makes his films appealing across geographical boundaries. However, some critics deemed Satyajit's penchant for a classical structure and permanent values unsuitable for grappling with the problems of contemporary reality. But various scenes from Ray's films suggest that such a claim is not well-founded. In Pratidwandi, the bureaucrats do not select the protagonist Siddhartha for a job, marking the young man as a communist because of his admiration for the courage of the Vietnamese people. In Seemabaddha, the senior executives of a business firm organise a bomb explosion in their own factory in order to gain benefits immorally. Due to the explosion, an ageing guard of the factory is badly hurt. In Jana Aranya, the young protagonist Somnath is asked "What is the weight of the moon?" during a job interview and an educated young woman from a lower middle-class family has to take up prostitution because of poverty. These scenes are understated, yet they disturb and unsettle the audience. Through his subtle approach, Ray provides bitter denunciations of corruption, callousness, and injustices prevailing in contemporary society.

Instead of acting like a propagandist, Ray wanted to make people aware of the persistence of certain social problems. Devi and Ganasatru show people's blind religious beliefs, Sakha Prasakha discloses the involvement of the top officials with bribery and corruption, Shatranj ke Khilari indicates the indolence and lack of political consciousness of the wealthy people, Aranyer Din Ratri reveals the insensitivity and boasting of the urban young men, and Mahapurush mockingly exposes the failure of the urban elite to embrace rational thoughts. Given the necessity of making people conscious of the same problems in present-day society, these films are still relevant today. Ray's films also made a departure from tradition by frequently including strong women characters. Sarbajaya in Pather Panchali and Aparajito, Manisha in Kanchenjungha, Arati in Mahanagar, Charu in Charulata, Karuna in Kapurush, Aditi in Nayak, Aparna and Jaya in Aranyer Din Ratri, Sudarshana in Seemabadhdha, and Ananga in Asani Sanket appear as bolder, more confident, and more resilient than the male characters. In an interview, Ray states that the inclusion of unwavering women characters reflects his own attitudes towards and personal experience with women.

Whenever we talk about radical filmmaking in the realm of Bengali cinema, Satyajit Ray's maiden feature (made in the face of tremendous odds) is mentioned. From Pather Panchali to his last film Agantuk, Ray never compromised on high standards, thereby making a huge impression. Having a greater familiarity with the oeuvre of Ray would enable people to understand the impressive qualities and importance of socially-meaningful cinema. We are surely in need of films that would make us perceive the beauty of a dewdrop on a blade of grass, strengthen our sense of humanism, and raise our social consciousness—hence, the everlasting relevance of the cinema of Satyajit Ray.

Dr Naadir Junaid is a Professor at the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments