A rebirth of the quota reform movement?

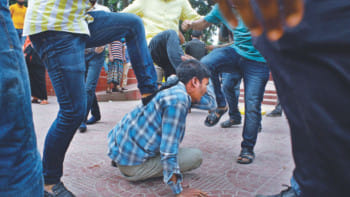

The mighty 2018 movement for the reform of the quota system in public jobs may make a comeback after a ruling by the high court on the contentious topic. The decision to abolish the quota system, taken in the context of wide-ranging protests against it in 2018, which includes the government employment quota for first- and second-class independence fighters, has been ruled unlawful by the High Court. After the ruling, students at Dhaka University brought out a procession against it. The old organisers of the quota reform movement from 2018 are again preparing to mount a new movement to protect the gains from their previous movement.

On the face of it, it may seem that a new movement has already started to form. Facebook groups have been set up, some by the old movement leaders, to call for an all-out movement. The abolishment of the quota system, even though it was not exactly the demand of the 2018 movement, was seen as a major victory for the quota reformists, who had endured repression and struggle to ensure that their demands were met by the government. The decade was host to many movements, but the quota reform movement was one of the more successful ones in terms of achieving its demands—something not all contemporary movements can claim to have done.

Even after the movement, the quota reformists were able to make political gains as two of its leaders were elected to the Dhaka University Central Students' Union (DUCSU) in the 2019 election. They continued their political journey by creating their own political party later, called the Gono Odhikar Parishad (GOP). However, the party suffered from divisions, infighting and scandals in recent years and a schism in the party had formed as a result. However, this new opportunity towards renewing their old movement is a chance for it to do some housekeeping and create a new united front to reignite the movement they had started in 2018.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), currently beleaguered by many worries and in the backfoot of Bangladeshi politics, may be able to make some political gains if they decide to invest in this movement. There may be some resistance from the new protestors in working together with the GOP and the BNP as both parties suffer from an image crisis. But working together in the movement may erase some issues and bring people together to fight as a united front against the decision to reinstate the quota system.

In his famous book, The Rebirth of History, Alain Badiou introduces the concept of historical protests as moments of mass uprising that signifies the return of active historical engagement, breaking away from periods of political stagnation. The quota reform movement was one of the closest instances to a one that we have seen in the 2010s. It mobilised the masses, mostly common university students who are worried about securing a job after their graduation, to engage in a mass movement that started as a rent-seeking attempt but soon turned into a bigger uprising. The movement leaders were even able to assert their political will by, first, winning in the DUCSU election, and then forming their own party.

Movements make leaders, and leaders make movements. As there is a fresh corpus of students in the universities who are eager to flex their political will, and as the old leaders now have a new found impetus to join a new movement, thereby rejuvenating their stagnant political projects, there is a palpable promise that a new social movement is about to be formed.

There may be questions around the demands that the students are making. After all, there needs to be some positive discrimination in the state to make sure disadvantaged communities get special treatment to counteract the adversities that they face. However, this positive discrimination argument does not hold against the main point of contention of the protesters, which is the freedom fighters' quota. Thirty percent of jobs will now again be reserved for descendants of freedom fighters following the new high court ruling. However, the freedom fighters' quota is often understood as a way of filling the civil service with Awami League loyalists, as the freedom fighter's certificate system is not foolproof and it is often easy for ruling party loyalists to secure those certificates for themselves.

Also, extending benefits reserved for freedom fighters to their third generation does not make sense. There may be some quota reservations for women, indigenous peoples, people with disabilities and from remote districts, but they should not exceed 10 percent, as was the demand of the 2018 movement. The protesters never wanted a full repeal of the quota system. This was done in a move to colour the movement leaders as prejudiced and acting against discriminated groups.

The demand for a just civil service is one that resonates with a large section of the youth, who look forward to getting a public job after graduation to get to a position of respect and security. In a country where the civil service is still the epitome of achievement and honour, it only makes sense to give students with the most talent a chance in the civil service, instead of filling its ranks with party loyalists.

Anupam Debashis Roy is a postgraduate student in political sociology at the London School of Economics.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments