Rethinking Bangladesh’s economic growth

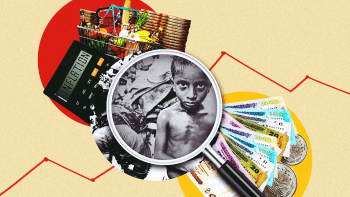

Imagine Bangladesh's banking sector restored to health, RMG contracts renewed, capital flight reversed, and flood damage repaired. Should we then consider our economic challenges resolved? While these are undoubtedly necessary first steps, if we stop there, we risk accepting the current economic path as fundamentally sound. In this column, this is precisely what we contest.

These fixes, while significant, address only the visible symptoms of the country's economic challenges. Our critique goes beyond these immediate concerns to question the very foundations of our economic thinking.

For years, Bangladesh has followed a development mantra centred on high GDP growth, low-wage manufacturing exports, trickle-down economics, and enabling infrastructure. But has this approach delivered on its promises?

Since 2001, Bangladesh has maintained an average annual GDP growth of six percent and is aiming for even higher growth in the future. But does GDP growth necessarily mean prosperity for the average citizen? Imagine a country where GDP grows by 10 percent, but 99 percent of that growth is captured by just one percent of the population. The remaining 99 percent see their incomes stagnate or even decline. This is high GDP growth on paper, but hardship for the majority. In Bangladesh, we've seen a similar, though less extreme, pattern. As GDP has grown, income inequality has also widened. The Gini coefficient, a measure of income disparity, has steadily increased alongside economic growth. This indicates that the benefits of our "economic miracle" are not reaching those who need them most.

Bangladesh has built its export economy on the foundation of low-wage manufacturing workers. However, growth based on cheap labour is neither desirable nor sustainable. This model is unstable because another country with even lower wages can easily undercut Bangladesh's ready-made garment (RMG) industry. Historically, Britain lost its textile manufacturing to cost-competitive Japan, and today, low-cost manufacturers like Bangladesh and Vietnam are displacing China. If this trend continues, Bangladesh will always be caught in a "race to the bottom," constantly at risk of losing industries to cheaper alternatives. In addition to the threat posed by lower wages in other countries, technological advancements and rising protectionism, such as friendshoring and nearshoring, are equally concerning.

The current strategy is undesirable because a low-wage economy is simply another name for a poor population. In the 1970s, Bangladesh may have had no choice, but 50 years later, how can it be considered desirable growth if the majority of people are expected to remain poor and accept low wages? The bottom line is that an economic policy based on low-wage manufacturing traps us in a path of continual economic hardship, rather than providing a ladder to prosperity.

Trickle-down economics suggests that benefits for the wealthy will eventually flow down to everyone else. However, in practice, this approach has led to massive wealth concentration at the top. Take, for instance, the extensive corruption during the last Awami League (AL) government. According to a report by a prominent local newspaper, over the last 15 years of AL's rule, nearly $150 billion was syphoned out of the country, marking the largest financial outflow in its history.

This case exemplifies a broader trend: instead of trickling down, wealth flows upwards. The situation in Bangladesh illustrates a key feature of crony capitalism—favouring those who already have wealth over those who work.

Ironically, Bangladesh's focus on infrastructure-led growth, intended to stimulate economic development, has exacerbated the problem. While infrastructure is undoubtedly necessary for the country's long-term development, the way projects were selected, financed, managed, and implemented significantly undermined their value. The various megaprojects built over the last 15 years have increased the country's foreign debt burden. Meanwhile, a rising dollar has made imports more expensive, unsettling the middle class and subjecting the poor to rising inflation.

The most vulnerable members of society, particularly those at the bottom of the economic ladder, have the greatest need for essential services like education and healthcare. Unfortunately, Bangladesh's public expenditure on these crucial sectors is low—one of the lowest in the world. In FY2024-25, the country allocated only 1.69 percent of its GDP to education and less than one percent to healthcare.

This underinvestment leads to poor quality of education and high out-of-pocket healthcare expenses. A sudden health crisis, such as a dengue outbreak, can push a low-income family into poverty or severe debt. Moreover, the long-term repercussions of inadequate education and health services are significant. These deficiencies deprive individuals of opportunities for meaningful employment and limit their contributions to both personal and societal advancement. It also deprives the economy of the human capital needed to sustain growth beyond the initial thrust from poverty.

The current economic model has failed because it prioritises short-term gains over long-term, inclusive development. It allows a small elite to capture a disproportionate share of economic benefits, neglects critical investments in education and healthcare, and relies on an unsustainable strategy of competition based on low wages.

Ironically, Bangladesh's focus on infrastructure-led growth, intended to stimulate economic development, has exacerbated the problem. While infrastructure is undoubtedly necessary for the country's long-term development, the way projects were selected, financed, managed, and implemented significantly undermined their value. The various megaprojects built over the last 15 years have increased the country's foreign debt burden. Meanwhile, a rising dollar has made imports more expensive, unsettling the middle class and subjecting the poor to rising inflation.

Given these profound shortcomings, we need a fundamental shift in our economic thinking. A new approach must prioritise the dispersion of wealth along with its creation, with policies aimed at reducing inequality and spreading benefits more widely. This means moving away from the failed trickle-down model toward bottom-up economic growth that directly benefits the majority. Central to this approach is increased investment in human capital. Considering Bangladesh's current underinvestment in education and healthcare, a significant increase in public expenditure is necessary.

In the quest for new economic policies for Bangladesh, we need to start by asking some basic but bold questions. As the capital-centric focus on economic development—which has concentrated resources and opportunities in Dhaka—has led us to the current stalemate of uneven growth and urban congestion, is decentralisation of economic activities the way forward? Does our comparative advantage lie only in low-wage manufacturing, or does its potential exist elsewhere? How can real income be doubled every decade? What strategies can be employed to achieve this ambitious goal?

Addressing these fundamental questions requires sustained effort and long-term commitment. The logic of decentralisation is rooted in the need to correct the imbalances created by our current economic model. China has lifted 800 million people out of poverty by developing secondary cities, creating regional economic hubs, and investing in infrastructure and human capital outside the capital. This approach not only spreads economic opportunities more evenly, but also harnesses the unique strengths and resources of different regions.

Perhaps Bangladesh's primary comparative advantage is its fertile soil, a gift of nature that cannot be outcompeted by another country. However, this valuable resource is currently underutilised. Instead of maximising its potential, much of the land is devoted to low-yield rice cultivation or lost to the proliferation of residential structures in rural areas and the expansion of commercial real estate. New thinking is needed to increase production through high-yielding rice and high-value agriculture—such as cultivating specialty crops or developing agro-processing industries—on the country's diminishing fertile land. This approach would allow Bangladesh to better leverage its enduring natural comparative advantage.

In this article, we have emphasised two key points. First, returning to the previous economic model will inevitably bring back the same economic challenges the country currently faces. Second, in exploring a new path for growth, focusing on agro-based development may offer a more sustainable and equitable solution. This approach is inherently decentralised, promotes a more dispersed distribution of economic activities, and leverages Bangladesh's natural comparative advantage in agriculture.

Dr Syed Abul Basher is professor of economics at East West University, Bangladesh.

Dr Salim Rashid is professor emeritus at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, US.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments