The locked archive: How bureaucracy silences Bengal’s poetic soul

The Dhanshiri River flows through Jhalakathi, its waters murmuring verses only a poet could translate. On its banks stands a whitewashed building—elegant, empty, and eternally locked. The Jibanananda Das Archive and Library, completed in June 2024 at a cost of Tk 3.14 crore, remains a monument in limbo. A year after construction, its doors are sealed. No books line its shelves, no scholars pore over manuscripts, no visitors commune with the ghost of Bengal's most haunting voice. The only sign of life? An adjacent eco-park where families picnic, oblivious to the cultural corpse beside them.

This is bureaucratic amnesia in concrete form. A wound inflicted not through malice, but through the mundane machinery of institutional neglect. To understand how a nation forgets its poets, we must dissect this negligence—not just as administrative failure, but as civilisational betrayal.

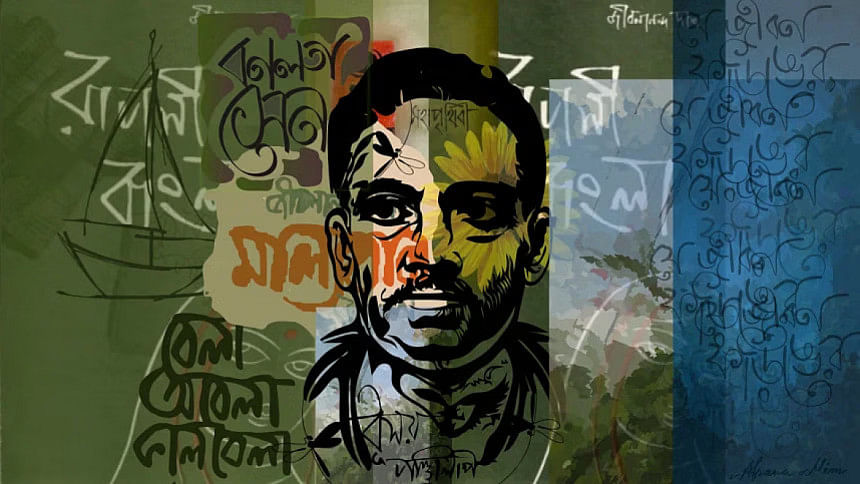

The poet who belonged to two Bengals

Jibanananda Das—Rupashi Banglar Kabi (Poet of Beautiful Bengal)—was a master of the liminal. Born in Barisal in 1899, his poetry wove the marshes of East Bengal with the mythic melancholy of Yeatsian symbolism. His verses captured Bengal's "moon-soaked nights" and "scent of ripe rice fields," becoming a shared lexicon for Bengalis on both sides of the 1947 Partition. Unlike Tagore's universalism or Nazrul's revolutionary fire, Das spoke to the intimate ache of place—the way a river's curve or an owl's cry could hold entire histories.

Yet this poet of belonging died in exile—struck by a tram in the then Calcutta in 1954, his manuscripts scattered, his legacy adrift. The Jhalakathi archive was meant to reclaim him. Built where the Dhanshiri River "frequently appears in his poetry," it promised resurrection. Instead, it became a metaphor.

Theories of forgetting: Why institutions fail memory

The Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) built the archive but refuses to operate it. Their admission is almost poetic: "We lack personnel and experience to manage cultural institutions." This isn't incompetence—it's rule-bound pathology. Institutions, like old trees, grow rigid in their niches. The BWDB digs canals; it doesn't curate poets. When a proposal to transfer the archive to district authorities vanished into bureaucratic ether "months ago," it revealed a truth: systems prioritise self-preservation over purpose.

The implementation gap further deepens the crisis. Our "Smart Bangladesh" vision glorifies libraries as knowledge hubs, yet policy papers ignore operational reality. Urban centres like Dhaka get digital resources; rural archives like Jhalakathi get shells without souls with little to no funding and logistical support. It's a national pattern: build, inaugurate, abandon.

Cultural capital depreciation completes this trifecta of failure. Das's work isn't mere literature—it's cultural currency. His archetypal imagery (owls, rivers, banyans) roots Bengali identity in the landscape. Locking his archive severs that root. As local poet Arup Talukder lamented, neglecting this space erases "the river and the region" that birthed Das's genius. When cultural capital decays, identity fractures.

Visit the site today and you'll see children chasing butterflies in the eco-park. You'll see the archive—windows shuttered, gates chained. This negligence inflicts three wounds. First, historical amputation. Das's manuscripts—fragile papers bearing lines like "For thousands of years I roamed the earth"—risk decay in inadequate storage. Lose them, and Bengal loses a piece of its consciousness. Second, civic distrust. When the state invests in culture as photo-ops, not sustenance, citizens grow cynical. As one visitor shrugged, "They build tombs, not libraries." Third, economic folly. Functional, Das's archive could attract scholars, tourists, poets. Instead, Jhalakathi's "picturesque facility" is a ruin-in-reverse, born dead.

The broader disease: Libraries as ghost towns

Jhalakathi isn't an anomaly. Across Bangladesh, cultural spaces gasp for air. Dhaka University's libraries now battle dust and budget cuts. The British Council Library, once a haven where "you could experience the bibliophile's ultimate thrill," now prioritises IELTS exams over literature, charging fees that exclude the masses. When libraries become luxury goods, democracy starves.

Even Partition memory suffers. The 1947 Partition Archive—a digital project preserving refugee testimonies—struggles for funding, while physical archives crumble. Societies that outsource memory to databases risk losing their texture: the smell of paper, the weight of a manuscript, the silent communion between reader and writer.

Healing this wound demands more than keys; it demands cultural rewiring.

First, the district administration must seize the archive immediately. Not through paperwork, but public action—a symbolic unlocking ceremony with poets, students, and Das's descendants. Bureaucracy responds to spectacle.

Second, community stewardship can be achieved through training local youth as archivists. Let fishermen's children curate Das's river poems. Much like Noakhali's folk memory projects, oral histories can animate texts.

Third, adopting digital-physical hybridity through scanned versions of the manuscripts for global access, while originals can be kept in humidity-controlled rooms. Let a villager touch the paper where Das wrote Banalata Sen.

Fourth, we need to ensure that at least 40 percent of the cultural budget is allocated for the operations and maintenance of such archives.

Epilogue: What the river remembers

The Dhanshiri still flows past the locked archive. It remembers young Jibanananda boarding steamers to Khulna, scribbling verses in the damp air. Rivers have long memories, unlike states.

Bureaucratic amnesia isn't passive, it's an active erasure of inconvenient truths, and Das knew this. His poem Land of Seven Rivers whispers: "How many bones must turn to dust for a country to be born?"

The archive's lock isn't just administrative failure—it's a referendum on what Bengal values. Until we wrench open those doors, we're not just neglecting a building; we're silencing the night-owl's cry across two Bengals.

Let Jhalakathi's shame become our reckoning. Unlock the archive before the poetry within us all goes extinct.

Zakir Kibria is a writer and political analyst. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments