The Name of a Plundered River

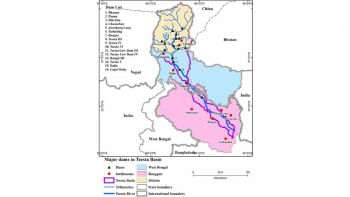

With the Teesta water-sharing deal between Bangladesh and India hanging in the balance for over a decade, West Bengal is planning to dig two new canals to divert more water from the river for irrigation and set up two hydropower projects on a tributary of the river, which will further worsen the sufferings of farmers in Bangladesh. According to these plans, as reported by The Telegraph, a 32km canal to draw water from the Teesta and the Jaldhaka rivers will be dug till Changrabandha of Cooch Behar district, and another 15km canal will be dug on the left bank of Teesta. And two dams named Teesta Low Dam Project (TLDP) I and II will be set up on the Bara Rangeet River to produce 71MW electricity.

This is clearly a violation of all international norms of transboundary river water management, as well as India's commitment given at the 37th meeting of the Joint Rivers Commission (JRC), held in New Delhi in March 2010. During that meeting, India agreed that "the Indian side would not construct any major structure for diversion of water for consumptive uses upstream of (Gajoldoba) barrage except minor irrigation schemes, drinking water supply and Industrial use" (Article 8, Annexure V).

At the same meeting, Bangladesh proposed a draft water-sharing agreement, according to which the Teesta water would be equally divided between Bangladesh and India, leaving 20 percent in the river to maintain ecological requirements. Had that draft agreement been signed, Bangladesh and India would each get 40 percent of the actual flow available at Gajoldoba point. After much deliberation, the two sides agreed in June 2011 that India would get 42.5 percent and Bangladesh 37.5 percent. But that agreement could not be signed due to the opposition from West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee. Though Mamata mentioned "shortage of water" as the reason for not signing the agreement, her government's latest move to withdraw more water from the river contests the validity of her argument.

Previously, Bangladesh and India signed an ad hoc agreement to share Teesta water at the 25th JRC meeting held in Dhaka in July 1983. According to the agreement, valid till 1985, 36 percent of the water from the Teesta would be allocated to Bangladesh, 39 percent to India, and 25 percent would remain unallocated. These shares would be subject to reallocation upon the completion of scientific studies by the Joint Teesta/Tista Committee. That reallocation agreement never took place, and India continued to withdraw water from the Teesta River.

According to a report published by The Daily Star last year citing data from the JRC, between 1973 and 1985 when the barrage was yet to be built in West Bengal, the daily average flow of water in the river in the last 10 days of March was 6,710 cusec (cubic feet per second). After the barrage became operational, the water flow started to reduce in the dry season while increasing in the monsoon. The flow in the Teesta starts to dwindle in October, and by December the river dries up. To meet the irrigation needs, the flow should be over 5,000 cusecs, but Bangladesh has been getting only 1,200-1,500 cusecs during the dry season, which sometimes drops to as low as 200-300 cusecs.

As a result, the drying up of the Teesta riverbed is threatening biodiversity, environment and ecology, hampering the livelihoods of thousands of farmers living in the northern region of Bangladesh. According to the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE), about 60 percent of an estimated 90,000 hectares of land in the river basin areas are left unutilised in the dry season. Many farmers in the Lalmonirhat district, who cultivate crops on the sandy char lands, are compelled to use diesel-run shallow machines to irrigate their croplands, which increases their costs of farming.

In this circumstance, if two new canals are dug and two new dams are built by the West Bengal government, the situation will become unbearable for Bangladesh during the dry season. Along with the Teesta, the Dharla River will also dry up because of water withdrawal from the Jaldhaka River. That's why Bangladesh needs to engage with India immediately in order to stop the new canals and put pressure to sign equitable water-sharing treaties.

Some Bangladeshi experts are concerned that sharing water based on the available water at the Gajoldoba point will not be fair nor optimal for Bangladesh, as the water flow is reduced by the hydropower projects even before it reaches Gajoldoba. Although the dams are termed "run-of-the-river" dams, which are not supposed to affect the river flow, the requirement of water storage for a long time to generate electricity and also the evaporation loss from the reservoirs reduce the downstream flows substantially, especially during the dry season. That's why the experts opine that Bangladesh should demand the minimum historical flow in the Teesta River, which is 4,500 cusecs.

Bangladesh should put pressure on India during bilateral discussions and raise Teesta and other transboundary river water-sharing issues as a mandatory condition for the continuity of India's access to Bangladeshi rivers, inland waterways and seaports. We also need to ratify the UN watercourses convention of 1997, which can be a great tool for a lower riparian country like Bangladesh to get its fair share of water from its big neighbour. According to Article 7.1 of the convention, "Watercourse States shall, in utilising an international watercourse in their territories, take all appropriate measures to prevent the causing of significant harm to other Watercourse States." Article 7.2 says, "Where significant harm nevertheless is caused to another Watercourse State, the States whose use causes such harm shall, in the absence of agreement to such use, take all appropriate measures, having due regard for the provisions of Articles 5 and 6, in consultation with the affected State, to eliminate or mitigate such harm and, where appropriate, to discuss the question of compensation."

It remains a mystery why Bangladesh, being a lower riparian country that suffers from unilateral water withdrawal from a big neighbour, still has not ratified the convention. It's high time Bangladesh ratified the convention and took the disputed water-sharing issues to international platforms to get a fair share of Teesta water from India.

Kallol Mustafa is an engineer and writer who focuses on power, energy, environment and development economics.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments