An unfinished struggle: Democracy, identity and reform

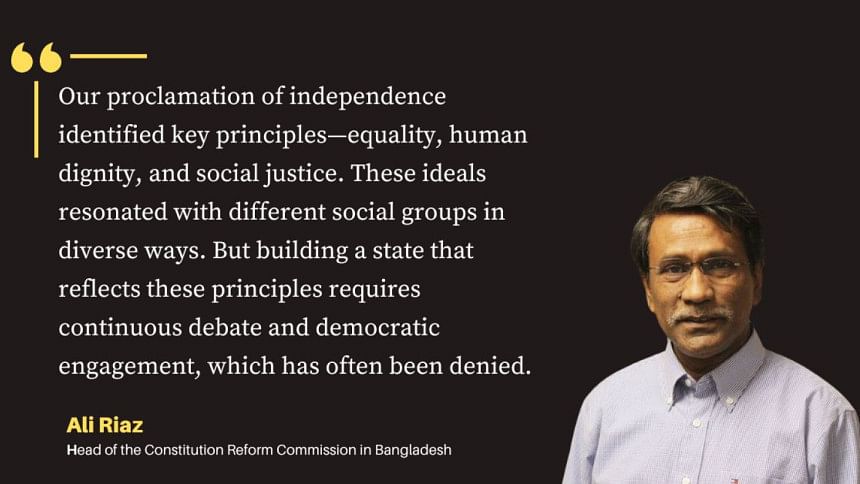

Professor Ali Riaz, head of the Constitution Reform Commission, talks to Monorom Polok of The Daily Star about Bangladesh's democratic struggles and the constitutional rights of individuals.

Recently, we have seen attempts to reshape the historical narrative of the Liberation War. What is driving these efforts, and how might they impact the future?

History is never a singular narrative. Every historical event has multiple perspectives. Take 1947, for example—there isn't just one version of what happened. States often try to impose an official narrative, whether in Pakistan, India, or elsewhere. Similarly, in Bangladesh, governments have shaped the narrative of 1971 to suit their interests. However, history is not linear or the product of any single party or individual. The independence movement was the result of a long historical process—events like the election of 1970, the mass uprising of 1969, and the military rule of 1958 were all stepping stones. In academia, history is always open to reinterpretation, but in Bangladesh, we have lacked the academic freedom to discuss historical complexities openly.

I disagree with the idea of a "regime-centric" history. While regimes leave their mark, history is shaped by broader forces. Since 1972, three themes have defined Bangladesh—the quest for democracy, economic development, and identity formation. Now that we have the opportunity to discuss these issues, different interpretations are emerging. There may be concerns about how some are revisiting history, but we should encourage open discussions rather than impose a singular, linear narrative. History is always subject to interpretation, and there is no "correct history," only correct facts.

If someone asked whether we have collectively failed to preserve or articulate the history of the Liberation War, I would say it is debatable. How do we preserve history? Even government documentation efforts have gaps. While official records exist, the voices of ordinary people—rural fighters, women in various capacities, and the working class—are often missing. This is not unique to Bangladesh. In India, it took decades to recognise the contributions of subaltern voices in the independence movement. When I showed my students the film Gandhi, they immediately asked, "Where are the women?" The same issue arises in Bangladesh's historical records. We've not done enough to preserve oral histories or document grassroots participation comprehensively. That said, history doesn't disappear—it resurfaces over time. The challenge is ensuring that all perspectives are acknowledged, rather than forcing a singular narrative.

It is widely accepted that political parties in power have selectively preserved or manipulated historical narratives to suit their interests. Does this distance us from the true essence of independence? We must first ask: was there ever a single understanding of independence? Different groups had different expectations. For the emerging Bangalee middle class, independence meant economic opportunity. For farmers, it was about fair prices for their crops. For students influenced by past struggles, it was about creating an egalitarian society. Leftists envisioned a socialist state. The one unifying goal was independence from Pakistan. That consensus has never been questioned. What has been debated is whether the post-independence state met the expectations of those who fought for it.

Our proclamation of independence identified key principles—equality, human dignity, and social justice. These ideals resonated with different social groups in diverse ways. But building a state that reflects these principles requires continuous debate and democratic engagement, which has often been denied.

Drawing a parallel to 1990, do you think there was a similar consensus on August 5, when Hasina's rule was widely seen as authoritarian and spiralling out of control? And are we now searching for a collective identity once again?

In part, I agree. There was a common enemy—not an individual or party, but an authoritarian regime eroding democracy and dismantling institutions to create a personalistic autocracy. That much was widely recognised.

But there is a crucial difference between 1990 and 2024. In 1990, the movement focused on removing General Ershad and holding fair elections, assuming the state would function properly afterward. No one questioned the constitutional framework. However, in 2024, the movement goes beyond removing a single regime. Over the past decade, it has become clear that the system itself needs reform. That is why we now see widespread calls for structural change rather than just leadership change. August 5 was the beginning of this process.

The constitution has been amended 17 times, yet democracy in Bangladesh continues to face frequent threats. As part of the Constitutional Reform Commission, what challenges did you face in addressing this issue?

Our main challenge was designing institutional safeguards to prevent future autocratisation. The 1972 constitution lacked strong accountability mechanisms. The prime minister held immense power with virtually no checks. Even after 1990, when Bangladesh transitioned from a presidential to a parliamentary system, the 12th amendment simply transferred all executive powers to the prime minister, creating a Westminster-style system with excessive centralisation.

In 1988, I wrote that Bangladesh was heading towards constitutional autocracy. By 1998, it was clear that removing a dictator was not enough—real reform was needed. Yet, the 12th amendment failed to introduce necessary checks and balances. Article 70, which prevents MPs from voting against their party, effectively turned the legislature into a rubber stamp. The judiciary also lacks independence. Courts have been heavily influenced by the executive, with politically motivated judicial appointments and interference in legal proceedings. True democracy cannot exist without an independent judiciary.

People often tell me, "Balance the power between the president and prime minister." But the issue is not about two offices—it's about creating institutions that ensure accountability. Power must be distributed so that if one branch fails, others can check it.

Even if institutional reforms are introduced on paper, can we expect these institutions to function autonomously given their history of political influence?

If you're asking about the next six months, of course not. Institutional change is a long-term process. A well-written constitution alone does not guarantee democracy. Political culture matters. Political parties must commit to upholding democratic norms.

However, if the constitution itself enables authoritarianism—by concentrating power in one office, undermining judicial independence, or preventing parliamentary scrutiny—then reform is essential. Right now, the prime minister controls the legislature, the judiciary, and the party. If we do not change this framework, democracy will remain vulnerable.

Ultimately, real change requires both constitutional reform and a shift in political culture. Institutions must be strong enough to resist political manipulation. Until then, the struggle for democracy will continue.

But it's not only about the next six months. The point is that if you're thinking of an immediate fix, it is very difficult and possibly close to impossible. But we must think in the long term and create those pathways. If not today, then tomorrow; if not tomorrow, the day after. If you create an independent judiciary, a secretariat free from executive influence, and fiscal independence, then you're starting the work. If you establish a judicial appointment commission with a fair and transparent selection process, while it may not happen tomorrow, in two or three years, it will bear fruit.

So, how do we go through this transition process? That's the challenge. That is where leadership is required and consensus needed. This is how reforms can be done—not just for the judiciary but also for the administration, the police. How do we make them independent and accountable? Not by changing individuals, but by creating systems. Transition is always painful—it has to be. Otherwise, it's just the status quo. People did not die for that—16 years of oppression, extrajudicial killings—they should not have died in vain.

Could you address the role of secularism in our constitution—how it has been defined and interpreted historically, and how it has evolved over time?

The notion of secularism has transformed over the years. The 19th-century idea of secularism mostly concerned the relationship between the state and religion. It emerged from a European context where religious institutions once dominated politics. We borrowed aspects of this model, but the interpretation of secularism has changed over time. In Bangladesh, secularism has sometimes led to Islamophobia, with the state treating Islamic practice as contrary to its ideals. Does this mean we should discard secularism entirely? No. But we need to ensure the protection of individuals because of their faith. Pluralism means recognising ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity, and protecting marginalised communities. Expanding secularism to include pluralism ensures equal treatment for all.

Instead of removing secularism, we should expand it to embrace pluralism under a broader umbrella. Political leaders embedded their ideals in the 1972 constitution, and while secularism was part of the state principles, it hasn't been consistently implemented. The real guiding ideals of 1971 were dignity, equality, and social justice, which should continue to define our future.

Has secularism reduced minority persecution in Bangladesh? Despite the 5th and 15th amendments, religious minorities have faced persecution. Minority persecution often stems from social and economic marginalisation, not just religious ideology. Secularism alone doesn't protect minorities; pluralism does. It provides a broader framework for protection—not just for religious minorities but for all marginalised groups. The state must play an active role in ensuring this protection.

In Bangladesh, an individual's access to constitutional rights seems to be restricted by financial class or family background. How can individuals truly access and practice their constitutional rights?

A crucial factor in protecting individual rights is accessible judicial recourse. The Constitution Reform Commission and the Judiciary Reform Commission recommended decentralising the judiciary. Legal processes should be affordable and accessible to all citizens. Rights must be enforceable and understandable, which is why we recommended simplifying the constitution to make it clearer for everyone. A constitution should be a social contract between citizens and the state, a guide for the nation, and a safeguard against oppression.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments