We must abandon our ecocidal mindset

In March this year, while visiting Sugandha Residential Area, Chattogram, I was alarmed to see that numerous trees had been felled along the roadside. Shocked, I took photographs and asked why they were cut down. The woodcutters said the decision had come from the residential authority. I filed a complaint with the Department of Environment (DoE) through its online platform, providing evidence of the illegal activity. However, five days later, my grievance was rejected without any explanation.

Seeking further clarification, I reached out to the Forest Department, which conducted an investigation into the matter. Their findings revealed that more than 100 trees had been cut down on both sides of the road in Sugandha Residential Area by the contractor in charge of widening the road. While the local councillor supervised the tree-cutting, neither the councillor nor the contractor took responsibility for their actions.

This is just one example of the relentless deforestation happening across Bangladesh which persists unchecked, as authorities largely turn a blind eye to its destructive impact on the environment. Existing forest and environmental laws are often ignored, leaving them only on paper without proper enforcement. Individuals and organisations recklessly clear out trees to serve their own agendas, without any repercussions.

This systemic negligence jeopardises Bangladesh's commitment to preserving its environment and natural resources. This issue is further compounded by frequent violations of environmental laws by governmental institutions themselves, often influenced by corruption or vested interests. For example, agencies have been accused of approving projects that involve the destruction of protected areas, cutting of trees, and disruption of natural habitats, all in violation of established laws and regulations meant to safeguard the environment.

The Chittagong Development Authority (CDA) is one such agency that recently suspended its plan of cutting trees to construct a ramp for the elevated expressway from Tigerpass to Pologround in the city in the face of public pressure. The initial decision followed significant opposition from local residents and environmentalists, who protested the proposed construction. Ironically, the original plan had received permissions from the Forest Department that authorised felling 46 trees, many of which were 100 years old and culturally significant.

According to our constitution, the state has a responsibility to protect and improve the environment and biodiversity for current and future citizens. Despite this, the government continues to sanction ecocidal projects and allow the destruction of natural resources and biodiversity.

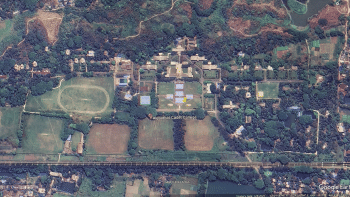

For instance, the decision to clear 52 lakh trees in the Mirsharai mangrove forest for an economic zone left 7,000 deer and other species without a home overnight, demonstrating an ecocidal mindset. The approval of a 102-km tourist railway line through three protected forests further led to the destruction of 670,000 trees and the blocking of 16 critical elephant corridors.

In June 2023, the Chattogram district administration cut down a mangrove forest in Kattali to create a sanctuary for birds. Supervised by the Forest Department, it involved the removal of many trees along the shores of the Bay of Bengal, raising concerns about the lack of oversight and the prioritisation of development over conservation.

Sometimes, despite the best intentions of the Forest Department and the Ministry of Environment, their efforts fall short due to power dynamics within the government. The recent killing of a forest officer by owners of illegal quarries has highlighted the waning power of authorities to enforce environmental laws. A study by Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) found that the Forest Department is facing several challenges. They don't have enough resources, which makes it difficult for them to do their job effectively.

Centralisation of administrative power prevents agencies outside specific domains from effectively implementing decisions, which hinders proper enforcement and accountability. As a result, the checks and balances to safeguard the environment are weakened, leading to continued violations and further damage to natural resources.

In the face of this crisis, urgent action is needed. The government's pledge to halt deforestation by 2030, made during COP26, must be translated into meaningful policies at home. Strict enforcement of existing laws, coupled with enhanced authority and resources for environmental agencies, is imperative.

Enhancing collaboration between the Forest Department, local administration, and law enforcement agencies is crucial. Establishing clear protocols and mechanisms for cooperation will streamline communication and facilitate swift action against environmental offenders. For instance, joint task forces could be formed to investigate and prosecute illegal quarrying operations or deforestation activities. Additionally, providing specialised training to law enforcement personnel on environmental law enforcement techniques can enhance their effectiveness in supporting the efforts of Forest Department.

Decentralising administrative power to empower forest and environmental officers at the grassroots level entails a fundamental shift in governance structure aimed at placing decision-making authority and resources directly into the hands of those closest to the environmental challenges. This process involves devolving responsibilities traditionally held by centralised authorities to frontline officers stationed in local communities. These officers, intimately familiar with the local ecosystems and environmental dynamics, are strategically positioned to swiftly respond to emerging environmental issues. With decision-making authority at their disposal, they can assess the situation, enforce regulations, and implement tailored conservation measures best suited to the specific needs of their surroundings.

Umme Humayra is a development trainee for Oxfam in Bangladesh.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guideline for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments