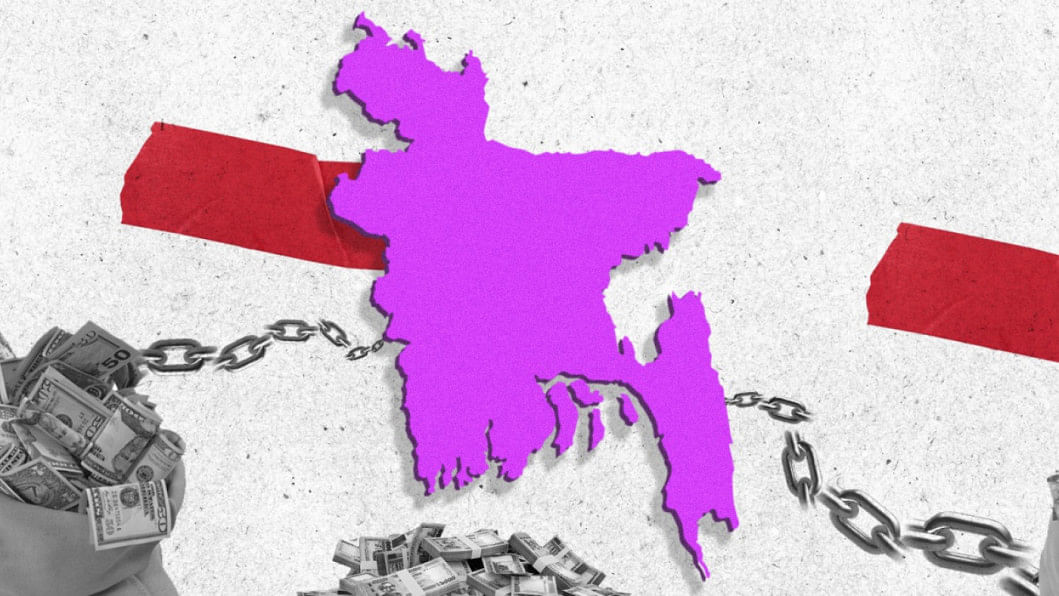

We must break free from our economic captivity

Once, long ago, the poet Nazrul sang of revolution, of freedom from oppression, but were he alive today, he might lament a nation enthralled—not to foreign invaders, but to a domestic oligarchy.

Bangladesh, a country of immense potential, now finds itself shackled by the iron grip of family-owned conglomerates. These corporate behemoths, shadowy leviathans cloaked in cronyism, have seized the state, becoming the financial sinew of Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian regime. Their stranglehold threatens not only our economy but also our democracy, suffocating the very ideals for which this nation was born.

In Japan's pre-war years, the zaibatsu—vast industrial and financial conglomerates—dominated the economy, leveraging their might to entrench authoritarianism. A striking parallel can be drawn with the past Awami regime in Bangladesh, where conglomerates like S Alam, Beximco and Bashundhara entrenched themselves across critical sectors, including energy, finance, real estate and media.

These conglomerates have become the faceless architects of a regime sustained by repression and corruption, extracting billions from an impoverished populace to line their pockets and bankroll autocracy. The modus operandi is insidious: monopolistic practices that stifle competition, inflate prices and hollow out public coffers.

Banks have been looted with impunity, state contracts distributed like party favours and regulatory bodies rendered impotent. Foreign investors, sensing the rot, flee; the economy's lifeblood haemorrhages. Yet the perpetrators remain untouchable, shielded by their proximity to power.

History offers a clarion call: economic monopolies and democratic governance cannot coexist.

The Allied dismantling of Japan's zaibatsu after World War II stands as a model. By decentralising economic power, breaking conglomerates into smaller entities, and instituting strict anti-trust laws, Japan laid the groundwork for a competitive, transparent economy. Similarly, South Korea's chaebol reforms curbed the dominance of family-owned conglomerates, injecting accountability into the veins of its economic system.

Bangladesh, too, must summon the courage to confront its oligarchs. Reforms must begin with an unflinching examination of financial records, exposing the labyrinthine networks of collusion between conglomerates and state actors. Here, examples abound: Brazil's Operation Car Wash dismantled an empire of corruption, revealing the pernicious ties between politicians and business magnates. The Zondo Commission in South Africa meticulously mapped out state capture by corporate elites. These efforts were not mere exercises in forensic accounting but acts of reclamation—nations reclaiming their dignity, their future.

The task before us is Herculean but not insurmountable.

First, we must establish a powerful, independent task force, armed with the tools of forensic accounting, data analytics and legal expertise. By dissecting financial flows, tracing cross-ownership structures and auditing procurement records, this body can expose the mechanisms of economic enslavement.

In South Korea, the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission worked in tandem with whistleblowers to unveil the rot within chaebols. Bangladesh must do the same, empowering civil society to join this battle.

Temporary nationalisation offers another pathway. Inspired by Japan's post-war reforms, key conglomerates could be placed under professional management for a limited period. This is not an invitation to chaos but an orderly transition: stabilising operations, removing corrupt actors and creating the conditions for fair re-privatisation.

The aim is not to destroy but to transform, to extract these entities from the toxic embrace of cronyism and return them to the people as competitive, transparent enterprises. Some will cry foul, invoking the spectre of economic disruption or accusing reformers of vendetta. Let them cry. The moral imperative is clear: the wealth of a nation cannot be the preserve of a few.

The lives of 170 million citizens—their hopes, their dreams, their right to dignity—are at stake. We must remember that these conglomerates do not merely control industries; they control futures.

Every inflated price, every siphoned dollar, every monopolised sector represents a child denied an education, a farmer deprived of fair markets, a citizen silenced by poverty. The battle is not just economic; it is existential. It is a battle for the soul of Bangladesh, a battle to reclaim our sovereignty from those who would sell it piecemeal for private gain.

Imagine a Bangladesh unshackled. Imagine industries where competition thrives, where entrepreneurs dare to dream without fear of predation by monopolies. Imagine a government no longer beholden to the oligarchs but answerable to its people. This vision is not utopian; it is attainable. It requires political will, legal reform, and, above all, a collective awakening.

Let us remember that history is a relentless tide. The zaibatsu fell. The chaebols were humbled. Even the most entrenched powers can be dismantled when a nation decides that enough is enough.

Bangladesh stands at such a crossroads. The choice is stark: capitulation or courage, stagnation or progress.

In the end, this is not merely an economic question but a moral one. Will we, as a people, continue to watch as our nation's wealth is siphoned away, our democracy eroded, our dreams deferred? Or will we rise, as we did in 1971, and declare that this land, this future, belongs to us all? The time for equivocation is over. The time for action is now.

For Bangladesh, the stakes could not be higher. For the oligarchs, the message could not be clearer: your time is up.

Bobby Hajjaj is a faculty member at North South University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments