What should women wear?

In May 2022, a young woman, who lives in Dhaka city, was verbally and physically assaulted at a train station in Narsingdi while waiting for a Dhaka-bound train. The assault was initiated by a local elderly lady who accused her of wearing "indecent clothes." Later, a few other men, waiting at the station, joined the elderly lady.

The video of this assault was recorded and posted on social media that led to protests and critical reactions among citizens and women's rights organisations. Subsequently, a case was filed and the accused were arrested. The accused later sought bail at the High Court, which was challenged by the lawyer of the victim who argued that a woman has the right to wear clothes as she pleases and cannot be harassed for this. In response, the High Court observed, "Do people not have the right to preserve their heritage, culture, and tradition? Is clothing not part of the culture? The socioeconomic status of society one is in should also be considered. Dhaka has one kind of environment and rural areas have their own" (The Daily Star, August 2022).

Many human rights organisations protested the High Court's statement; for instance, Ain O Salish Kendra issued a statement saying "it goes against women's equality, constitutional rights, internationally recognised human rights standards, and the current government's policies regarding women empowerment." In contrast, groups of students at the Islamic University in Kushtia, Dhaka University and North South University arranged human chains, holding placards with slogans like "Culture against social norms and values are unacceptable," "Stop public nuisance in the name of right to dress" and endorsed the High Court's observations (The Daily Star, August 2022).

To what extent do such contentious opinions on the Narsingdi event represent the prevailing collective norms and values of our society in relation to women's rights to wear clothes as they please? Thanks to a recent nationally representative survey (sample size 10,218; survey conducted in November-December 2022), now perhaps we can reflect on the question in an informed and systematic manner, rather than speculating on it or trying to answer it based on anecdotes. The survey asked if people agree with the statement "I believe women can wear dresses as they please."

About 40 percent of the respondents agreed with the statement and the rest disagreed. However, there is a gender difference: only 32 percent of the men respondents agreed compared to 49 percent of the women. People's perceptions did not vary much based on where they lived – urban or rural. Younger people tend to agree more compared to the older, although the differences are not very pronounced. Similarly, people's opinions differed very little across income status, but views started to change at a higher income level. For instance, 40 percent of the respondents earning Tk 5,000-30,000 per month said yes to the statement, but it came down to 30 percent (a significant drop) when their income level reached Tk 50,000 and above. The same trend can be observed across educational levels – about 40 percent of people with no or primary education to higher secondary level responded yes to the statement, but such positive opinion went down to 36 percent (a moderate decline) for higher education (graduates and above) cohort.

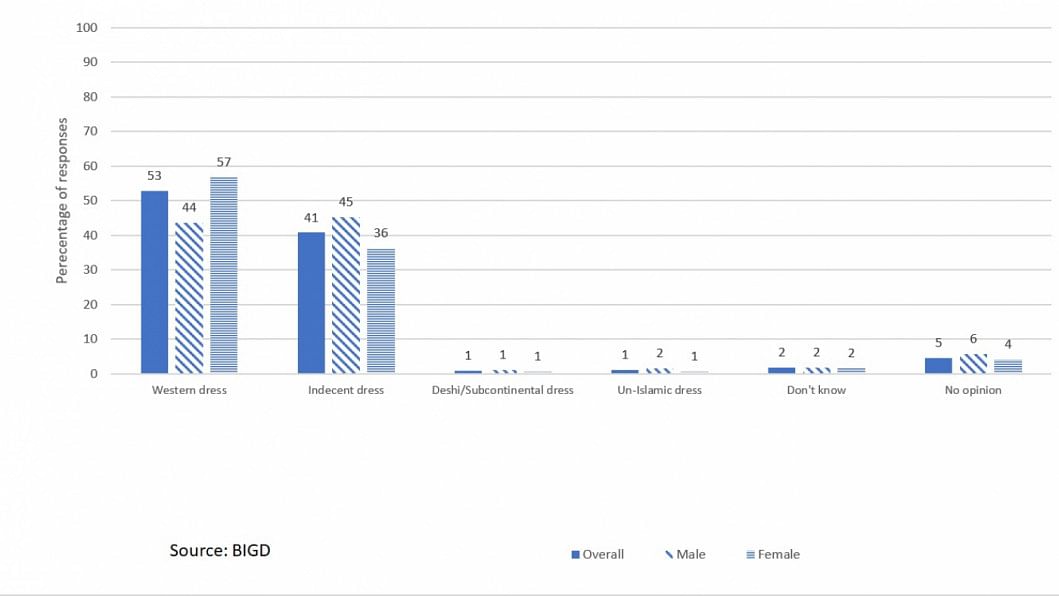

As noted earlier, about 60 percent of the respondents were not in favour of women wearing clothes to their liking. They were asked what specific types of dresses they found objectionable. Western clothes top the list (53 percent), followed by indecent clothes (41 percent). Among those who disliked Western clothes, there are more females (57 percent) compared to males (44 percent). When asked what they meant by "indecent," the majority mentioned sleeveless tops and kameezes, while other categories of objectionable clothes include shorts, fitted/body hugging, and see-through/transparent. Only one percent mentioned that they find un-Islamic clothing (such as not wearing a burqa or hijab) unacceptable. People against deshi or sub-continental clothes also constituted a mere one percent of the respondents.

More respondents belonging to the lowest monthly income group said they did not like indecent clothing, while more respondents in the highest income group said they did not like Western attire. Differences in responses across educational levels are not very pronounced, but it appears that highly educated respondents (graduates and above) reported more disliking towards "indecent dresses" compared to others.

What meta-level social dynamics can we discern from our findings? Two features stand out: firstly, societal norms, as they relate to women's choice of clothing, tend to be generally diffused in the society and not sharply clustering around economic class, gender, education, location, and demographic factors. Is this due to increasingly generalised accessibility to media, both electronic and social, which is flattening the normative landscape? Secondly, what is deemed as objectionable seem to be predominantly informed by ethnic-cultural identity (anti-Western) which is also secular, i.e. hardly based on religious values. Other findings indicate that women, across economic classes, tend to be anti-Western, and such a value also seems to slightly cluster around people with high income. These are some of the normative "puzzles" that we cannot attempt to deal with in the short spaces of an op-ed.

Dr Mirza Hassan, Syeda Salina Aziz and Sumaiya Tasnim are faculties and researchers based at the Brac Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments