Why bringing the laundered money back may not be easy

December 9 is observed worldwide as the annual International Anti-Corruption Day (IACD). No country is free from corruption; it is as much a national problem as international. Corrupt practices and failure to prevent and control it in one country facilitates corruption in another, especially high-level corruption including money laundering.

What often fails to draw sufficient attention are the systemic loopholes that drive high-level corruption and illicit international financial transfers on both supply and demand sides. Ironically, the suppliers are most of the worst ranked countries in global corruption indices, while some of the "best performers" are the beneficiaries. The latter group is also regarded as the global leaders of the fight against corruption, financial crime and money laundering. For every dollar received by developing countries as ODA, at least 10 dollars are lost through money laundering.

IACD is a reminder that nearly all countries in both categories who have ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), have pledged to take concrete and collective action against corruption at both national and international levels. This year's theme for IACD is "Uniting with Youth Against Corruption: Shaping Tomorrow's Integrity." The idea is to amplify voices of the young integrity leaders to express their concerns and aspirations, with the hope that their call will be heard and acted upon.

IACD is being observed this year in Bangladesh against a backdrop scripted in golden letters about the youth's invincible courage and power that led to the fall of one of the world's worst kleptocratic-authoritarian regimes, at an extremely high cost of deaths, injuries and multi-dimensional and multi-level violation of human rights. The youth's vision of a new Bangladesh is anchored in the total rejection of long years of state capture that facilitated and provided impunity to corruption, especially at high level, creating floodgates of money laundering.

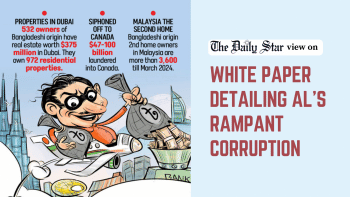

The humiliating defeat of the authoritarian regime opened unprecedented opportunities for transition towards a "new Bangladesh" that's free from abuse of power, institutionalised corruption, kleptocracy and unbridled money laundering. Mandated by people power, the interim government has rightly attached top priority to the state reform agenda with specific emphasis on corruption control as well as repatriation of stolen assets.

Public expectation is high that the bulk of the billions of dollars laundered out of the country over the years may be brought back. The governments and relevant agencies of the leading host countries of Bangladesh's laundered assets appear willing to provide legal and technical support in a spirit of goodwill to the transition opportunity led by the interim government and solidarity with the youth-led people's uprising.

However, the outcome of this goodwill and solidarity in the form of actual return of stolen assets is easier to be expected than realised. There is no denying that our laws and policies were not enforced, relevant institutions like the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit (BFIU), Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and Attorney General's Office were captured, rendered dysfunctional and professionally bankrupt. The good news is that, unlike its predecessors, the interim government has the will to act and appear on course to fast-track reforms and practical action towards mobilising the necessary capacity to proceed with the due process consistent with national and international legal standards and practices.

However, the process of repatriation of laundered assets is long and complex, requiring multi-stage collaboration and cooperation between our relevant institutions and those of the countries who have let our laundered money and assets to land there. As illicit as these are, laundered money from Bangladesh has been invested in host economies. Although such transfers and investments are de jure illegal in every such country, syndicates of consultants including law firms, trust experts, offshore specialists, real estate agents, accountants, regulators and banking and financial services counsels facilitate deals in a manner that the dirty money is welcomed quite conveniently and becomes "clean" until proven otherwise in a complex and long-drawn process.

Before every laundered penny is returned, it must be proven in the host country in the due process that it has entered there illegally and actually belongs to Bangladesh. This is why, as per credible assessments, the global experience of the rate of repatriation is no more than only one percent of trillions of dollars stolen a year. The only instance of Bangladesh's success of bringing back stolen money from Singapore took six years—from 2007 to 2013. Nevertheless, given the interest of the host countries to be helpful, there is nothing wrong to expect that in "new Bangladesh," it may not necessarily take that long.

While it is our responsibility, host countries also have the burden not only to assist the repatriation process, but also ensure due diligence and accountability of the syndicates of enablers to prevent further flow of funds. Unfortunately, the track record in most cases is far from encouraging. There is much to be desired about their compliance with the standards set by the Paris-based global money laundering watchdog, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

FATF reports that most of the host countries of Bangladesh's laundered money have a well-developed regime to control money laundering. But almost all are also reported to be short or inconsistent of supervision and accountability across various relevant sectors. There are weaknesses in reporting and investigation of suspicious transactions. Some are even found to have less than desired levels of understanding of money laundering risks. Lack of effective mitigation measures against vulnerabilities of the high-end real estate agents, lawyers, accountants, trustees and investment advisers also persist.

This is not to underestimate the importance of stronger legal, institutional and policy reforms and actions at our end. However, of equal if not more importance, is greater control and compliance at the demand side. No real progress in prevention of money laundering can be expected without more concrete actions against welcoming the flow of illicit financial transfers in host countries. Concerted and collective action at both ends of money laundering are long overdue not only for repatriation, but more importantly for effective prevention.

Dr Iftekharuzzaman is executive director at Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments