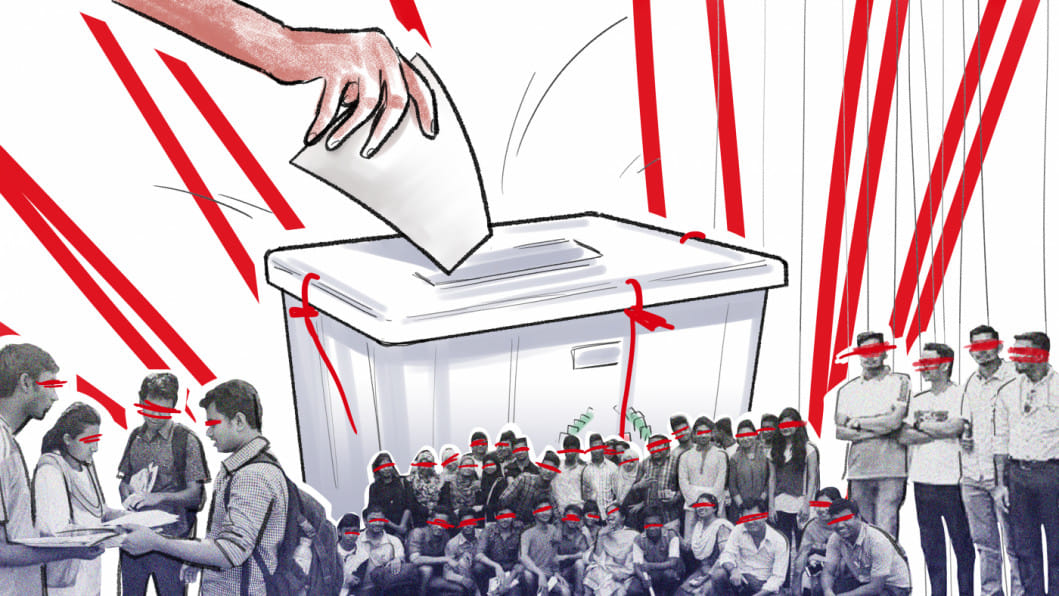

Will the political deadlock discourage first-time voters?

I remember learning in school that it was the citizens' responsibility to the state to participate in the democratic process by casting their votes in elections. I always took my textbooks seriously, and even on an intuitive level, it made sense. As a citizen of a democratic country, of course it's my responsibility to vote, to contribute to the running of my country.

During the last national election, I was 19 and was excited to be able to vote for the first time. But having received my national ID (NID) card shortly before the election, my name did not appear on the list of voters. Fast forward five years, and I have learnt a lot more about the democratic process. Another election is in the offing, and even though I want to feel excited again, I simply cannot.

Less than a month out from the election, as a voter, I'm looking for discourse on the issues that concern me. If I'm going to vote for someone, is it not fair to ask whether or not that individual—or the party they represent—is going to do anything for me and my demographic? The youth horn is tooted at every turn these days. The demographic dividend is here, and the youth must be empowered—we have been hearing so for years now. But are the Bangladeshi youth being put to work?

On the internet, Gen Z have grown used to the spectacle of Western democracies, wherein public debates take place on the eve of elections. They also see elections taking place in neighbouring India, where one party wins one state but fails to hold on to their majority in another. The young Bangladeshi knows that plurality is important in politics, and plurality of opinions should come to the fore during elections. Yet, so close to the election, it takes more than a thorough look at the news to find a politician saying anything that has anything to do with real issues that citizens face.

As a working professional in my mid-20s who is trying to make life go his way in an increasingly expensive Dhaka, I wonder what is being done to make sure my employment potential does not diminish in the coming years. The Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2022 says that 12 percent of individuals with higher education in the country are unemployed, up from 11.2 percent in 2016-17. The situation is bad, the trend seems worse, but this presents a ripe opportunity for any politician to attract the votes of young individuals who are new to the employment race or are just about to enter it. Yet, there seems to be little space left for them when conversations are laser-focused on seeking flaws in the opposition camp.

Politicians may be unaware of an interesting aspect of the young voters who will be queueing up to vote for the first time on January 7, 2024: their perception of what a democracy can be is different from what those who came before them thought.

The 20-year-old of today was born in, say, 2003. The ruling party has been at the helm for as long as this demographic has been socially conscious. While the horror stories of the opposition's actions may be enough to sway older voters, it will never have the same impact on most first-time voters, who were mere children the last time the mantle of power had changed on these shores. On the internet, Gen Z have grown used to the spectacle of Western democracies, wherein public debates take place on the eve of elections. They also see elections taking place in neighbouring India, where one party wins one state but fails to hold on to their majority in another. The young Bangladeshi knows that plurality is important in politics, and plurality of opinions should come to the fore during elections. Yet, so close to the election, it takes more than a thorough look at the news to find a politician saying anything that has anything to do with real issues that citizens face.

The depressing fact is that there is no lack of issues that can effectively engage the youth; there is only the politicians' lack of desire to engage them.

Road safety has been a massive point of concern for students all over the country, as young people are fed up with watching their friends and peers die unnecessary deaths. In 2020, the country erupted in protests against sexual violence, a mobilisation mainly dominated by students—young women and men who want to see change. The state of higher education in the country has been a worry for all, with the best universities in the country languishing at the lower end of global rankings. Added to this is the fact that politics and administrative mismanagement have held back public universities from becoming fully fledged centres of knowledge. Bangladesh is known on the global stage as a country that is on the frontlines combating climate change, but not much is being done to address the concerns of the young individuals who will have to live on a planet that is way hotter than it should be.

Looming in the backdrop is the fact that speaking up about anything comes at a premium now. There is widespread confusion—which often turns into abject fear—over what the Cyber Security Act might do to someone practising their constitutional right to freedom of expression. Cases like that of Khadijatul Kubra of Jagannath University—who languished in jail for over a year for hosting a webinar where a guest made comments deemed contentious—only add to this fear. A recent study conducted by Bangladesh Youth Leadership Center (BYLC) and Brac University's Centre for Peace and Justice found that 71.5 percent of respondents aged between 16 and 35 feel unsafe expressing their opinions on public platforms like social media.

Of course, whenever their hand has been forced, the youth have broken through these fears to voice their concerns. But far too often, these concerns have been brushed aside by the powers that be. The Road Safety Movement of 2018 captured the country's attention. The murder of Abrar Fahad at Buet triggered massive protests against rampant politics in public universities. The construction of a coal-fired power plant in Rampal, adjacent to the Sundarbans, was protested for years. But such demands from young people are usually met with promises of reforms that either do not materialise or are toothless in nature. In some cases, the demands are altogether ignored.

Some may point to a lack of political organisation as a reason behind young people's demands being unmet. Many say that subversive political influences have foiled these protests. But the opportunity that an election presents to politicians is that they can reverse the attempt to disregard and depoliticise the youth's concerns. A party that shows any level of awareness towards the youth's demands could buy enormous political capital with the most important demographic of this country for the next 20 years. But such efforts are yet to be seen. It will represent a monumental failure in our politics if discussions leading up to the election address neither the most common concerns of Bangladesh's largest age demographic, nor the fears that impede their inclination to express themselves freely.

It's understandable that the political climate will dictate political discourse, and as long as the political climate remains dysfunctional, it's practically futile to hope that the discourse will offer anything else. Yet, sitting in traffic jams induced by processions protesting the 20th political blockade in 25 days, the youth are waiting for a politician to bring up, say, intersectional feminism, or at least to mention a framework to ensure long-term employment of graduates in this country. Someone needs to talk about protecting free speech, protecting the climate, about road safety and the safety of women in public. Otherwise, Bangladeshi politics risks alienating an entire generation.

Azmin Azran is a journalist at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments