Is Yunus’s sentencing an ominous message for foreign investors?

"Handle at your own risk"—is what the foreign investors will take away from Monday's extraordinary sentencing of Nobel laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus.

It is this unintentional but unequivocal message that may prove to be most damaging for Bangladesh and the economy: it poses to further shrink the historically modest inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI).

Policymakers and academicians have long acknowledged that FDI is a key element of a successful development strategy as it generates the capital and technology transfer at the scale needed to bring about economic transformation. Bangladesh's FDI inflows have always been low for a host of reasons including red tape, inadequate facilities and human resources—and less-than-ideal enforcement of the rules and regulations and the laws of the land. With Yunus's verdict, this cynicism surrounding the enforcement of the laws of the land may only amplify. Why so? Because it took a great deal of legal and mental gymnastics and suspension of logic to ensnare him.

A noble provision in the Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006 that calls for sharing five percent of the company's profits with the employees and various worker funds was deployed to hook Yunus. Yunus, who chairs the board of Grameen Telecom, did not comply with this provision. In other words, Grameen Telecom did not share its profits with its employees.

All very well, but this argument comes caving down when one learns that Grameen Telecom is a not-for-profit organisation. How can a company that does not make any profit share any profit with employees?

Here, too, another loophole was created by brute force: Grameen Telecom owns 34 percent shares in Grameenphone, the country's leading mobile phone operator and the biggest company in the bourses. Grameen Telecom surely takes its share of profit from Grameenphone, but that amount is ploughed back into social businesses.

However, the employees of Grameen Telecom felt they were entitled to five percent of Grameenphone's profits. An irrational demand, but one which Grameen Telecom agreed to indulge.

Even here, faults were found, with this court-agreed settlement between Grameen Telecom and its employees labelled as a bribe. And the fact that this transaction was done belatedly was viewed as money laundering.

Another issue that was found with Grameen Telecom's conduct was that it did not regularise its 60-odd contractual employees.

When Grameen Telecom started, it aimed to empower rural women by equipping them with mobile phones that would be used for moneymaking activities. With the easy availability of mobile phones, this core activity of Grameen Telecom has now become redundant.

The non-profit has subsequently let go of many of its staff, keeping 69 of them on a contractual basis while enjoying the frills of a permanent job. The reason they are kept on a contract is that their job is dependent on as and when Grameen Telecom gets a work order.

At this point, one must wonder how many establishments are taken to court for not sharing five percent of their profits with their employees and not turning all contractual workers into full-time staff.

If a globally-revered, upstanding citizen like Yunus—who faces nearly 200 cases—can be harassed legally in this manner, what hope is there for foreign investors?

The message is clear: if they do not toe the line, they can be implicated by hook or crook.

Already, Grameenphone, where Norwegian state-owned Telenor has controlling stakes, had to face the wrath: it was barred from selling SIM cards for six months for below-standard service, although evidence suggested otherwise.

Surely, the manner of Yunus's sentencing does not add to the broader investor confidence in Bangladesh, and the data points already are not promising.

In the past couple of years, the already low levels of FDI have already started shrinking as the multinationals are barred from repatriating their profits from Bangladesh due to pressure on foreign currency reserves, according to top executives, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal.

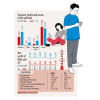

Take the case of FY2022-23, which is the latest full-year data available. On paper, the net FDI inflows were $3.25 billion, down 5.5 percent year-on-year. But a closer look at the data shows that just a quarter of the sum was actually fresh inflows, with as much as 72.9 percent of the FDI inflows last fiscal year just reinvested earnings.

In FY2021-22, reinvested earnings made up 59.4 percent of the net FDI of $3.4 billion. Conversely, 39.2 percent of the inflows were fresh investments, up from 32.6 percent the previous year.

Given the strain on the dollar stockpile is unlikely to subside any time, it will be a while before the multinationals are allowed to take their profit out. If they can't take the profit out, what incentive is there for them to park their funds in Bangladesh?

And after Yunus's most arbitrary sentencing, the incentive shrinks further.

Zina Tasreen is a journalist at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments