Is it possible to escape from the seduction of smartphones?

A week or so ago, I was scrolling through my newsfeed when I found an interesting title of an episode of Al Jazeera's popular show, The Stream: "Why are Gen Z and Millennials ditching their smartphones for dumb phones?" It immediately caught my attention; I couldn't help notice the irony of clicking on a programme about young people weaning themselves off their smartphones while I was devouring my smartphone's content of the day. It was a bit like a non-member eavesdropping into an Alcoholics Anonymous group made up of a generation considered being literally born in the era of smartphones. I mean, being from Gen X would put me in their parents' (I refuse to say grandparents) category, and what could I, who spent most of her youth in the analogue days, find anything in common with them, right? Well, actually, quite a lot.

It was uplifting and sobering to see that these young people are smart enough to realise the need to opt for ways to take back control of their lives, to "live in the moment" and improve their social skills. The wisdom of a 24-year-old who switched to a dumb phone because he had spent 15 years of his life with a smartphone, blew my mind, "I don't hate smartphones—I just feel I'm too immature to use it."

There's no point in denying that I am totally dependent on my phone for practically everything—being in touch with loved ones, colleagues, acquaintances, the tailor, AC Moinul (guy who fixes the air conditioner), the news, and, of course, my daily fill of mindless scrolling and reel-watching. In fact, my partner and I play a vicious mind game of trying to make each other feel guilty by saying "You really spend too much time on your screen" just when either of us are in the middle of our smartphone fix. We deny and claim that "I just picked it up" to check if there was any breaking news or important message from our daughter who lives in a different time zone. But deep down, we know the ugly truth: the bug of relentless connectivity to some world or the other has infected us, and there seems to be no cure.

It's not that we don't know that we are abusing this amazing, smart device that feeds us whatever it thinks we need to be fed with. We know that if we look at the screen just before hitting the bed, the bright screen fools our brain into thinking it is daytime, and hence wakes it up more instead of allowing it to get ready for a few hours of much-needed respite. There is scientific evidence that the unpredictability of what will come next on the screen gives the brain high levels of the feel-good hormone dopamine, which makes us want more and more of these hits. Now I know why I can't even look at the book I have been trying to read since January, and instead go back to watching bits and pieces of Friends or endless reels on contraptions to get the perfect jawline.

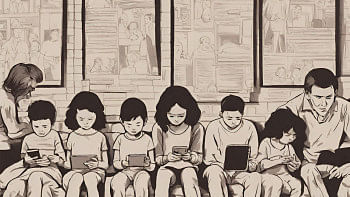

But let's get back to the topic of the show. Apparently, young people are realising the damage they are causing themselves by being ruled by the smartphone. Gen Z, the generation born into this technology, has no other idea of, say, socialising, except through social media. Face-to-face interaction or even talking on the phone feels alien to them. Social media addiction or "problematic use of social media," whatever you may call it, is a cause of worry not just for parents and guardians but for young people themselves. Studies have found that too much time on social media (which is usually through their smartphones) or any kind of screen time can have serious side effects such as anxiety, not being able to interact face to face, having difficulties concentrating, insomnia, constant headaches, and severe mental health problems such as anorexia and suicidal thoughts. So how can people, especially teenagers and young adults, get out of the irresistible lure of the smartphone?

It is a lifestyle issue, said Jose Briones, one of the panellists introduced as an advocate of digital minimalism and offline living who actually switched to a "dumb" flip phone for basic functions like text and call. He recommended using a smartphone during work hours (since for many people work requires them to be on their devices) and switch to a dumb phone after work.

Another panellist, Shayonee Dasgupta, said she had taken great lengths to detox herself from her smartphone, which was causing her anxiety. Since even disabling apps did not work (as she would reinstall everything right after) she installed an app that would impose a heavy monetary fine whenever she violated her screen-time limit. The prospect of losing so much money incentivised her to keep within the limit.

But is there a healthy limit for screen time? Journalist and author Sophia Smith Galer argued that the idea is too generalised, and that the healthy limit for screen time really depends on how individuals use it. For some people, those four hours of screen time may be very productive, while for others it may actually be harmful. Parents and guardians have sued companies for what they consider promoting harmful content to their children, and there is credible evidence to support this view. According to Sophia, the technology can be intentionally harmful, and she proposed that the algorithmic feeds should be altered for the better. That would put the onus on the companies, and only legislation can make them think of public interest over profits.

Data privacy is a constant worry around social media and smartphone use—something that we still have not been able to solve. Thus, the trend to turn away from smartphones even if it's for a certain period and turning to their dumb predecessors may be catching on, especially in advanced countries where the awareness level regarding these harmful effects is high.

In Bangladesh, however, smartphones still rule, and for many it is a status symbol. You will find very few people, especially teenagers and young adults—regardless of economic backgrounds—who consider their smartphones as their most precious possession. For many of us, it is like a body part we never want to be out of sight. But we, too, are facing the fallout from overdependence on these devices, especially overconsumption of the content they offer, social media in particular. Taking cues from discussions like the one on The Stream, which, by the way, shows the good side of online technology, we can take back the power from our controlling, devastatingly alluring, smartphones.

Aasha Mehreen Amin is joint editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments