What will it take to be Smart Bangladesh?

I have to admit, I like the sound of it – Smart Bangladesh; it has a nice ring to it. That we are going to transform ourselves from "Digital Bangladesh" to "Smart Bangladesh" (by 2041) gives an impression that something revolutionary is about to happen, albeit after a wait of almost two more decades, when many of us will either be too old, or just dead, to appreciate its impact.

It is, nonetheless, a seductive term that promises not only having everything digitised – from banking to basic healthcare – but we as citizens will know exactly how to use the technology at hand and become the "smart citizens" that we were destined to be.

This is hard for some of us to grasp, having grown up in the analogue days when, if somebody said, "You need to be smart," it usually meant getting a nice haircut, or wearing an ironed, expensive-looking outfit from the given decade, alongside a pair of clean, shiny shoes. Funky sun-glasses could be added for extra "smartness."

But this is not what entails a "smart citizen" of a "smart country." Then what is it, pray tell?

This seems to be the greatest mystery of the year, and no one really knows exactly what it means. Yes, you have to be tech-savvy in the virtual world, but weren't we told we had already achieved that, at least officially, through our "digital" Bangladesh, where everyone knows how to use a smartphone, post heavily edited pictures of their blissfully happy and successful selves on Facebook, and make endless cringeworthy TikTok videos? So what more will we achieve through being 'smart'?

Like any brain-eating conundrum, it is always good to start at the beginning. In 2008 – a good 14 years ago – the Awami League government announced the launch of "Digital Bangladesh" as part of its Vision 2021 and in line with the party manifesto. Experts will be able to properly evaluate how successfully this vision has been realised. But from a layperson's point of view, so far one cannot deny that some major strides have been made in digitisation.

The two horrific years of the Covid pandemic can be seen as the acid test of just how technologically ready we were to handle months of lockdown.

Thousands of students were able to connect to their educational institutions (at home and abroad) and attend online classes, however faulty the connections were at times. Newspapers were published either fully or partially through remote operations. The work-from-home model was successfully implemented across the board in almost every sector. Even healthcare, to some extent, was provided through digital platforms. Like the rest of the world, we in Bangladesh became Netflix addicts, gourmet chefs, health freaks, cat video followers, and self-proclaimed life-skill coaches. We took Zoom meetings to a sickening level. We registered for vaccines and actually got the dates; even our courts went virtual.

And nothing could beat the expertise we developed in digital shopping; from groceries to gourmet meals, cosmetics to cleaning services – everything could be ordered online and delivered at the doorstep.

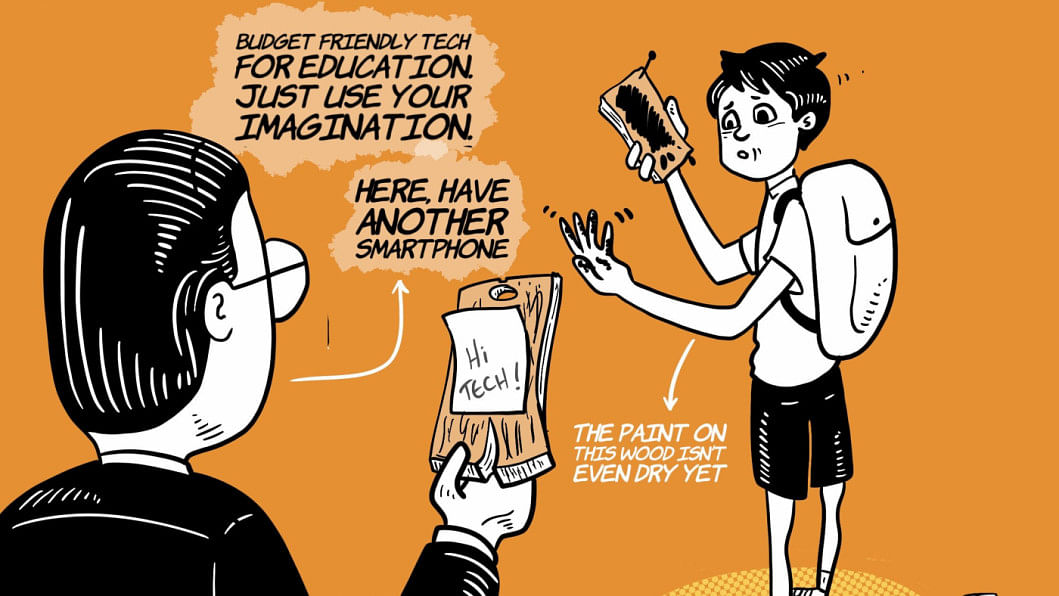

But while the educated, middle class and upwardly mobile went on to a turbo mode of digitisation, there were millions who were left behind. Remote learning through the internet did not reach students in villages, especially in remote areas where they had no internet, smartphones or even TV. Thus, the benefits of the digital leap remained quite skewed and tilted towards a small section of the population.

That's why we are not exactly jumping with joy at the prospect of a further technological leap that a "smart" Bangladesh is promising to deliver. Perhaps it's the word "smart" that seems to nag like that stubborn piece of meat stuck between the teeth. Despite being part of the tech revolution, where even our land records are becoming digitised, there are little inconvenient truths that may question the smartness of our actions in critical areas that may dim the technological smartness we have achieved.

How smart, for instance, is it for forests to be cleared to make way for government-owned training academies, guest houses, recreation centres, and offices? The same is true for our rivers and canals – all victims of grabbing and pollution. How smart is a nation that has done virtually nothing to protect its natural resources?

The catchphrase "smart cities" is certainly catchy – but in our case, still a figment of the imagination. Adnan Zillur Morshed, an architect and expert on urban planning, in his article in this daily last week, bemoaned how we have not incorporated walking as part of our urban lifestyle. In my view, walkability is the smartest benchmark of a city where 44 million people live, traffic jams eat away hours of our time while burning expensive fuel and messing up the air, and draining away our productivity, every single day. We have footpaths, but they are taken over by hawkers, plagued with open manholes, potholes, and truant motorcyclists speeding by to make sure that a walk will be as hazardous and as unpleasant as ever. From a pedestrian's point of view the city is far from being 'smart'.

How smart is a city where a seven-minute car ride becomes an hour-and-a-half-long ordeal, and where walking is a hazardous prospect?

How smart is it to have a digitised system to evaluate a vehicle's fitness, when the streets are filled with unfit buses playing speeding contests and are driven by drivers with fake or no licences, who can crush people and speed away with complete impunity?

How smart is it to talk about women's empowerment when a simple walk or ride to the workplace may entail being molested on the way?

How smart is it to crush diversity of opinions on digital platforms with the threat of arrest and years of imprisonment?

The list of just how "unsmart" we are is boringly long and endless.

The launch of the Tk-22,000-crore Dhaka Metro Rail next week, which will use all kinds of mind-boggling, advanced technology, and which reminds one of Bangkok's speedy Sky Train, does make one want to believe that we are on our way to being a smart nation.

But while technological innovation and learning how to use that technology are key steps to a smart economy, let's not forget that a smart economy is also one that promotes entrepreneurial spirit, is sustainable, uses resources efficiently, and aims to increase the quality of life of all citizens.

Are we on the right track?

Aasha Mehreen Amin is joint editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments