Could we (please) do better in controlling food prices?

The new government in Bangladesh needs to continue the distribution of food essentials in full force in the coming months, in order to keep the cost of living low for vulnerable groups. The months of December and January, which span the Bangla calendar months of Poush and Magh, ring in the new harvest season. However, for the rural poor and the impoverished families in urban areas, winter also brings about food shortages and other hardships which are aggravated by the cold and accompanying dry, polluted air. Already, there have been reports of increase in food prices in domestic markets during the post-election weeks.

Last year, the country witnessed food price increases in the double digits for months in a row, and there are still no signs of the prices cooling down. These increases leave their mark on the budget since, even if there is a deceleration of inflation, recent inflationary hikes have already hit consumers' pockets hard. According to one BBS study at the end of 2023, one in every five households in Bangladesh was food insecure.

Another issue the government has to be vigilant about is that merchants employ familiar tactics to inflate prices well before Ramadan, aiming to avoid scrutiny during the month of fasting, which is only less than two months away, according to a spokesperson for the Consumers Association of Bangladesh. One does not need to speculate that the prices of beef, lentils, and onions will go up during Ramadan. The government must, in a coordinated fashion, take steps to maintain market stability and address price gouging.

According to a Bangladesh Trade and Tariff Commission (BTTC) report from last month, the prices of beef and onion have shot up despite adequate supply. The Ministry of Commerce must employ special initiatives to monitor the supply and price list of essential items like rice, wheat, edible oil, sugar, lentils, chickpeas, onion, garlic, ginger, turmeric, dry chilli, eggs, and dates. Concerns have been raised that the reduced import of wheat has led to increased dependence on rice among the poor, thereby intensifying the pressure on rice supplies and exacerbating food insecurity.

Another issue the government has to be vigilant about is that merchants employ familiar tactics to inflate prices well before Ramadan, aiming to avoid scrutiny during the month of fasting, which is only less than two months away, according to a spokesperson for the Consumers Association of Bangladesh. One does not need to speculate that the prices of beef, lentils, and onions will go up during Ramadan. The government must, in a coordinated fashion, take steps to maintain market stability and address price gouging.

A basic and fundamental tenet of economics is that the cost of food depends on the price you pay and on your budget. For an average household, which spends 70 percent of its budget on food, every month is a struggle to balance its budget. A World Food Programme (WFP) study showed that in November 2023, an average of Tk 2,833 was spent on food for one person, reflecting a six percent increase compared to the same period last year. Data shows that hunger and food insecurity vary depending on the region, season, and social class. A recent Prothom Alo report noted "variations in the price of rice across different categories, with Barishal, Khulna, and Chattogram recording higher prices compared to other divisions." According to the "Grain and Feed Update" report by the US Department of Agriculture's Foreign Agricultural Service and the Global Agricultural Information Network, in the second week of December 2023, the average retail price for coarse rice rose to Tk 51.35 per kilo, up 1.3 percent from the previous month's price. Rice price has been increasing since October 2023, primarily due to high inflation and higher transportation costs (contributed to by blockades and hartals). The report predicts that the supply of newly harvested rice into the market may lead to a slight reduction in prices in January.

The Bangladesh Market Monitor-November 2023 report by WFP captures the anxiety I feel. "Despite satisfactory internal production and public procurement, national average retail prices of rice are still very high, primarily due to rising costs for fertilizer and irrigation as well as import challenges." While Food Secretary Ismail Hossain recently declared to a Bangla daily that, "There is no shortage of food for the poor in the country," his confidence in the market mechanism is misplaced.

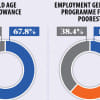

Needless to say, ministries must improve law enforcement in the essential commodities market, and government agencies must continue Open Market Sales (OMS), Food Friendly, Food for Work, Vulnerable Group Feeding, and Vulnerable Group Development programmes.

To ensure success of the above initiatives, the state must effectively identify vulnerable people and thereby determine the nature and duration of the support they will need, ensure that the genuinely poor and vulnerable people receive support, and introduce a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) mechanism to ensure efficiency, transparency, and accountability in the distribution chain.

Market manipulators are creating a supply crisis, and the inability of policymakers to take any measures against them has left many families struggling to make ends meet since wages have not increased at the same pace as inflation. More concerningly, sudden jumps in food prices and other essentials also impact low-income people who are otherwise considered "non-poor" as they are still vulnerable to poverty due to adverse income shocks.

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and works for Change Healthcare, Inc, an information technology company. He also serves as senior research fellow at the US-based International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments