Please spare us your ‘khela’

A new parlance, "khela," has been added to the political dictionary by the ruling party and is being regularly used as political jargon. The English equivalent of the word would be "sports," but because of the manner in which the word is being expressed by the Awami League, the word "game" perhaps expresses more volubly the true meaning of the word "khela." And the word conjures up in one's mind something creepy, something unscrupulous and unfair. And if one were to adduce some sinister intent in that word, would one be much wrong?

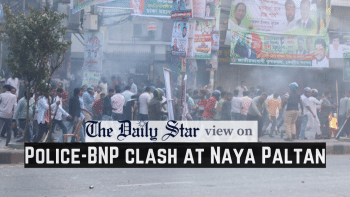

We do not know what exactly the Awami League general secretary means when he warns the BNP and advises his cadres to gird for khela on December 10. People are perplexed and even worried that the khela of December 10 may be portentous of bad things. The Awami League threatens the BNP with dire consequences if it crosses the line on December 10, while the BNP accuses the ruling party of provocation and instigation. We may have seen a preview of that on Wednesday (December 7). A clash broke out between BNP members and the police in Dhaka's Naya Paltan area, in which at least one person was killed and 30 more injured in the clash (as of 7pm), and the party claimed that at least 200 of its members including top leaders Ruhul Kabir Rizvi, Shahiduddin Chowdhury Annie and Amanullah Aman were arrested.

The issue of the site of the December 10 meeting has not been fixed, and the BNP sees a "game" here too that the government wants to play.

However, the general public are least interested in the so-called game, or its rule, or that it would be played out on political turf that remains heavily uneven and heavily in favour of the ruling party. But the game already started long before December 10; it started from the very day the opposition parties sought to exercise their political right by organising rallies and meetings.

The first game is that of keeping the public transports off the roads and rivers. The fact that the transport owners as well as the leaders of transport workers of all definitions are a cabal under the ruling party umbrella, such anti-people steps are easily implemented. The puerile excuses that were offered to justify the transport strikes did not wash with the public, and it was not difficult for anyone to see through the disingenuous tactic that was deployed to impede the gathering and spoil the BNP meetings. Strikes were called in Khulna, Mymensingh, Barishal, Rangpur, Sylhet and Moulvibazar, Rajshahi etc, starting a couple of days before the scheduled meetings – in some places, for an indefinite period. But interestingly, those were called off soon after the BNP meetings ended. Does one need any more examples of the gross malintent behind such a scheme?

But did this ploy succeed? Hardly. On the contrary, reportedly such impediments helped to gel the BNP supporters even more strongly together. And what the government failed to understand – and if it did at all, it perhaps couldn't care two hoots for the fact – that such a policy is a two-edged weapon. In fact, not only the BNP supporters, but the Awami League supporters also suffer from the same distress that is intended for the opposition.

The spectre of conditional politics is not new either. It would be of benefit to the readers to jog our memory. Nothing has changed in the last 10 years. Please recall the events related to the BNP rally on January 5, 2016 and March 2012, where six and eleven conditions, respectively (and 19 directives to boot), were imposed on the BNP to fulfil before it could hold the meetings.

And we are constrained to repeat what we said in 2016 in these very columns that when a political programme is subjected to restrictive provisos, admittedly for the sake of law and order and public safety, it does not say much about politics or our polity and even less about democracy. That a security agency of the government should remain the sole authority to determine where, when and how a political party should organise its programme is indicative of the deep malaise in our system. May we ask if the DMP imposes the same conditions when the ruling party or any of its appendages organise meetings or rallies in Dhaka city?

Another intimidating game that the ruling party plays is going after the opposition leadership, picking them up on flimsy, concocted offences, which makes the law enforcement agencies a laughing stock. The overdrive of the law enforcement agencies targeting BNP cadres is not surprising either. In one case, one who has been out of the country for nearly a year has been framed in the charge sheet. And the police have found this particular time propitious now to revive the arson case of 2018 against BNP men.

But it is not the first time such ploys have been used to obstruct the opposition's political programmes. Ever since the Awami League came to power in 2009, this very tactic was applied as a tool to prevent the BNP from exercising its political rights – a thoroughly anti-constitutional act.

Given that such a policy is being enforced by the ruling party, utilising the agencies during the run-up to the election, which is only a year away from now, such actions can hardly breed confidence in the administration under the Awami League to remain impartial and conduct a fair election.

Brig Gen Shahedul Anam Khan, ndc, psc (retd) is a former associate editor of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments