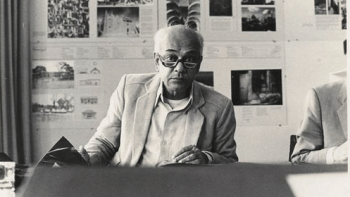

Shamsul Wares: A teacher who inspired generations of architects

Do we have a national fetish to celebrate accomplished people around us only after they perish? How often do we express gratitude to our teachers when they are still around? Being an educator myself, I understand, even if imperfectly, how much students' appreciation means to a teacher.

Today, I would like to thank a professor who inspired generations of architects in Bangladesh.

Shamsul Wares is known as a fiercely passionate teacher who professes architecture as a philosophy of modernism—one that views the challenges of space-making through the lens of 20th century aesthetic experiments in abstraction, platonic clarity, and humanism. His growth as an iconic teacher in the Department of Architecture at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) paralleled the trials and tribulations of a post-independent country and the evolution of its built environment.

As an architect, Shamsul Wares has produced a robust body of design work, ranging from residential houses to urban parks, from factories to institutional buildings, from cinema halls to shopping malls and apartment complexes. "Wares sir" built an intellectual bridge between the aggregate design legacy of Muzharul Islam, Louis Kahn, Constantinos Doxiadis, Paul Rudolph, and Stanley Tigerman during the Pakistan era and the generations of architects that contributed to the development of what has been called a "Bengal Stream" in architecture in post-independence Bangladesh. The kind of architecture he advocated in his classroom is deliberately abstract, where overt social and historical representations are muted in favour of platonic formal expressions. We learnt from his position on aesthetic modernism, one that is cognitively powerful without having to resort to any kind of semiotic adventures or show gratuitous associations with the power structures of history and society.

***

Towards the end of Nathaniel Kahn's acclaimed documentary, My Architect: A Son's Journey (2003), there is a perplexingly poignant moment. I reflected on it in a review of the documentary, "Inside the Capitol building … Shamsul Wares delivers a startling, if not the ultimate, message: that personal failings should not blind us to the genius of a great artist and that a son must seek his father not always in the father's fulfilment of familial duties, but sometimes in the humanity of his aesthetics." To describe the genius of a great artist, Wares likened Louis Kahn to "our Moses" who, in his view, gave Bangladesh an unmistakable symbol of democracy, a timeless Parliament Building that captures the highest expression of modernism. The most dramatic part in all of this was not Wares's "genius father" statement, but the tears that rolled down his cheeks while stating it. Nathaniel Kahn stated on several occasions that, for him, the Shamsul Wares moment in the documentary unexpectedly became his project's intellectual epicentre. Many people agreed.

Shamsul Wares is known as a fiercely passionate teacher who professes architecture as a philosophy of modernism—one that views the challenges of space-making through the lens of 20th century aesthetic experiments in abstraction, platonic clarity, and humanism. His growth as an iconic teacher in the Department of Architecture at BUET paralleled the trials and tribulations of a post-independent country and the evolution of its built environment.

It is hard not to wonder what Wares's tears meant both for the documentary and the state of architecture in Bangladesh. Were they tears of gratitude? Joy? Emotion? Days after I first watched the documentary in New York City, I ran into India's celebrated architect Charles Correa at a soiree hosted by MIT professor Stanford Anderson at his beautiful waterfront house in Boston. Upon hearing that I was from Bangladesh, Correa asked me about Shamsul Wares, particularly the reason for his tears in My Architect. Kahn's work is great, but why cry, Correa asked. I was at a loss for words but found myself ruminating on the question, too. I tried to convince Correa that Bangladeshis become sentimental while talking about Kahn's Parliament. There are several potential reasons for this: the edifice parallels the country's political journey to independence; Kahn had a monumental influence on the architectural evolution in this country; and the country had found a national symbol of architectural pride in this building. This is emotional stuff, I argued with Correa, who seemed unconvinced. Years later, I told Sundaram Tagore, director of Louis Kahn's Tiger City (2019), that weeping inside Kahn's Parliament has not been uncommon.

Shamsul Wares's tears also reveal his quintessential pedagogy: architecture is a lifestyle, an abstraction of life itself. As his students, we found such teaching inspirational and contagious. In our young minds, he was our Plato, who made us conscious of praktike (doing) and gnostike (knowing) in design education. Wares's metaphysics of the art of buildings had a profound influence on us. Architecture is an arduous journey, one that requires perseverance, determination, and love. Architecture must simultaneously undertake the archaeology of the aggregate human experiences of the past, while endeavouring to forge ahead into the future. This is probably the reason why he often cites the Danish existential philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, "Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards." Wares demonstrates a deep understanding of the project of history—his panoramic, nuanced, and non-conforming history classes used to spellbind us—yet he steadfastly remained committed to architecture's ability to shape a humane future.

***

Shamsul Wares grew up in Chandpur, a small city southeast of Dhaka, near the confluence of two mighty rivers of the Bengal delta: the Meghna and the Padma. The geographic energy emanating from the meeting of two delta-shaping rivers must have left an indelible impression on his worldview, one that accommodates and triggers multiple lines of thought as a critical vantage on life.

When he arrived in Dhaka in the early 1960s to pursue higher studies and visited the East Pakistan University of Engineering and Technology (EPUET), his chance encounter with the newly minted programme of architecture there determined what his lifelong passion would be. The decade of 1960s was a period of "great transformation" for the then East Pakistan, politically and socially. The political and economic asymmetries between West Pakistan and East Pakistan that disempowered the people of the eastern wing of the state created a robust culture of protest and resistance in East Pakistan. For the people of East Pakistan, this was a time of national soul-searching.

The decades of 1970s and 1980s were a time of a regionalist spirit in architecture around the world as the idea of a universal "modern" was challenged for its alleged failure to incorporate local characteristics of a place. Wares, however, maintained a sophisticated distance from the discourse of regionalism in architecture. He never advocated any comforting and phenomenological symbolism of placeness in the built environment.

Richard "Dik" Vrooman, an American architect and academic from the Texas Agricultural and Mechanical University (Texas A&M University), came to Dhaka in 1961 for eight years to create a faculty of architecture at EPUET. Other Texas A&M University professors who joined Vrooman included James C Walden, Jr (1962-66) and Samuel T Lanford (1963-65). The mission was to educate local architects, filling the void of architectural design expertise warranted by the burgeoning building industry, particularly during Ayub Khan's "Decade of Development" in Pakistan. Vrooman and his colleagues were supported by, among others, expatriate architects like Daniel C Dunham (1962-67) and Jack R Yardley (1966-68). Part-time faculty included East Pakistan's first professionally trained architect Muzharul Islam. Joan C Walden taught basic design and Mary K Donaldson art history. Prominent artists like Rashid Chowdhury, Hamidur Rahman, and Abdur Razzak also taught in the architecture programme. Abdullah Abu Sayeed introduced Bangla literature, while Mary Frances Dunham lectured on European art and music. Roy Vollmar and Gus Langford, two of Louis Kahn's associates stationed at his local office in Dhaka during the construction of the Parliament Building, were occasional instructors. This was a time of extraordinary academic fertility that characterised architecture education at EPUET.

Shamsul Wares was an intellectual product of this vibrant and cosmopolitan environment, as well as the political consciousness of 1960s East Pakistan. He graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1968, during the height of Bangalee agitation for self-rule in East Pakistan. After graduation, he worked at Vastukalabid, the acclaimed architectural office of Muzharul Islam. In 1972, he joined the architecture programme as a lecturer at the age of 26. His pedagogy began to demonstrate the cosmopolitanism, modernism, and multidisciplinarity of the programme that had trained him.

The decades of 1970s and 1980s were a time of a regionalist spirit in architecture around the world as the idea of a universal "modern" was challenged for its alleged failure to incorporate local characteristics of a place. Wares, however, maintained a sophisticated distance from the discourse of regionalism in architecture. He never advocated any comforting and phenomenological symbolism of placeness in the built environment. While acknowledging the significance of the place in making architecture meaningful, he resolutely and deliberately wanted to transcend its causal influence, in the same way Rabindranath celebrated Bengal and its people, nature, rivers, and rain only to ultimately surpass them all to reach a universal milieu of humanity. In The Apu Trilogy (1950s), Satyajit Ray depicted an intimate portrayal of life in rural Bengal while narrating a universally understood sapiens story. There is a reason why his Pather Panchali (1955) won the Best Human Document award at the Cannes Film Festival in the year of its release. In a similar vein, Wares's modernism aspires to a universal value system that neither glorifies nor rejects the place.

***

Asked to suggest one book to an aspiring architect, Shamsul Wares's answer was bewilderingly beautiful, "If it is concerned with architecture, I do not know of one book that surpasses all other books. Thirty years ago, I would have suggested Space, Time and Architecture by Sigfried Giedion. Right now, I think we are in a much-diversified state, and one book is too few to understand the dynamics of architecture today. However, if I must pin down my suggestion to one book, I would suggest a novel … The Bicycle Thief." Recommending Luigi Bartolini's haunting novel (1946) portraying the urban despair of postwar Rome—transformed into a devastatingly poignant film (1948) by Vittorio De Sica—to students of architecture is one instance of Wares's cosmopolitanism, enlightenment, and wisdom. Learning about architecture through iconic buildings may be too parochial or didactic a suggestion. The ability to see the promises and perils of architecture through the humanity of a father-son saga, as in The Bicycle Thief, or through the existential angst of city life, shows the irresistible allure of Shamsul Wares's design pedagogy.

Aristotle once said, "Those who know, do. Those who understand, teach." Shamsul Wares understood, and hence taught. Being his student has been our privilege.

This essay is an excerpt from a forthcoming book titled Shamsul Wares: Teacher, Mentor, and Architect.

Dr Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, urbanist, and professor. He teaches at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, and serves as executive director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at BRAC University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments