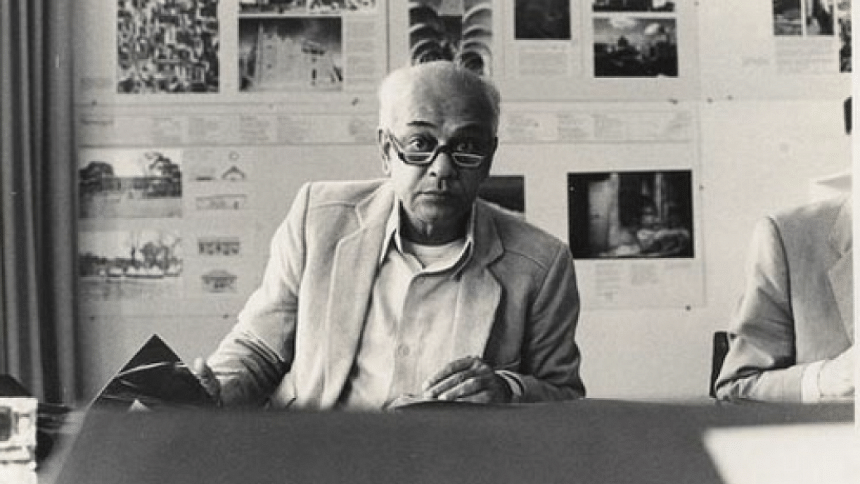

Muzharul Islam (1923-2012) remains the most eminent and influential architect of Bangladesh, and also unique among all the architectural stalwarts in South Asia. Since the 1950s, through the design of numerous institutions, laboratories, universities, housings, office buildings, and residences, he not only introduced the norms and language of modern architecture in the country, but deepened our understanding of architecture culture. He was involved as a political activist because of his resolve to address social inequities and injustices, which led him to work with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on the ideas for physical planning, social housing and integrated villages. December 25, 2023 is the 100th birth anniversary of this giant of a man. The article is a commemoration of his birth centenary.

"Who is the best Bengali architect?" Prof Santosh Ghosh, an eminent Indian architect from West Bengal and a friend of the master architect in Bangladesh, Muzharul Islam, raises the question. "The first was Vidyadhar Bhattacharya, a Bengali architect, who planned the city of Jaipur in Rajasthan in 1727 and designed several houses, which are visited by many tourists. Jaipur's 250th anniversary was celebrated in 1977, and I was lucky enough to be present at that event. Tribute to Vidyadhar was done through a dance performance. The Rajasthan state government named a suburb Vidyadharnagar, a park was also named after him. We Bengalis have not done anything. Muzharul Islam is the best Bengali architect of the 20th century, this should be remembered by the architects of two Bengals forever" (Sthapati Muzharul Islam, edited by Abul Hasnat, Bengal Publications, 2015).

Islam is described as the doyen of Bangladesh's architecture who introduced modernism in the country as well as the highest ideals of thinking about and making architecture. With his designs for the Fine Arts Institute (Art College), Public Library (now the Dhaka University Library) and the two housings in Azimpur in the 1950s, He established the norms and language of modern architecture in then East Pakistan. Since then, he designed an incredible array of buildings and complexes: the Science Laboratory, the Road Research Laboratory, the NIPA Building at Dhaka University, housing in Joypurhat, housing in Rooppur (now demolished), the Jiban Bima Tower (now mutilated), five polytechnic institutes, and the National Archive. He also produced the master plans for two universities—Chittagong and Jahangirnagar—in which few buildings were built. Between 1964 and 1970, he is reputed to have designed nearly 200 residences, establishing the paradigm of a modern dwelling in Dhaka.

All those buildings and complexes were not mere answers to pragmatic requirements, but were a part of a larger effort to build up the technical and cultural foundation of a nation. I describe it as a nation-building enterprise. Such efforts extended to inviting top-notch architects of the world to create paradigmatic architecture in Bangladesh. The most well-known is perhaps the National Parliament Complex in Dhaka, designed by the famous American architect Louis Kahn. Not too many people are familiar with the fact that Muzharul Islam was originally invited to design the complex; instead of accepting the offer, he suggested getting Kahn for the project. He was also instrumental in getting Paul Rudolph, another renowned architect, to design Bangladesh Agricultural University in Mymensingh.

Besides his architectural work, Islam was deeply involved in political and cultural activism. He was an active member of NAP (Muzaffar), and campaigned for physical planning in light of the socialist vision of the country after 1971. Chhayanaut would hold its early sessions in Islam's Paribagh compound. In the early 1980s, he was instrumental in establishing the Chetana Architecture Research Society that played a key role in establishing the role of history and culture in the making of architecture at a time when the profession was dominated primarily by commercial motives. As a member of the first master jury of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, he was responsible for guiding the objectives of the award.

An equation of Vidyadhar, the architect-planner of Jaipur city, with Muzharul Islam, a modernist architect who wished to plan for a better future, is certainly knotty. Vidhyadhar's quasi-modern mystical city and Islam's modernity orbited different locus. Vidhyadhar appeared at the dawn of colonial rule in India and Islam at its formal closure. In that interim period—a substantial 200 years—Indian and Bangalee societies underwent a tremendous transformation, mostly from without and much to its detriment.

It was clear from his very first projects that Islam would practise as an architect with a clear commitment to the ideological goals and promises of modern architecture. To him, modern architecture was more than an aesthetic trope of the foreign and the new—it was the most viable instrument to bring about a humanist society in the aftermath of colonial disruption.

Islam's critique of colonial rule, mounted relentlessly and on every occasion that he could find, made colonialism not only an oppressive system focused on economic exploitation, but the singular cause for the great displacement and dislocation—of cultural, existential and traditional values. It was obvious that in such a dislocated condition, Bangalees would ape the British. The evidence is in the hundreds of zamindarbaris all across Bengal, with their Palladian facades, Corinthian capitals and fake pediments, all of which were an unabashed aspiration for things European.

How to be original and located in such a condition? How to restore an authentic architectural condition after the loss? That was the challenge for Islam when he returned from the US in 1953 after his training in architecture. Since then, until the 1990s, he designed buildings and complexes that provided a new language of architecture for the country—modern yet defined by the milieu and climate of Bangladesh. He established his private practice in 1964 and named it "Vastukalabid," with vastukala referring to the art of dwelling. Recalling the ancient Sanskrit notion of "vastu" within a modernist worldview certainly reveals Islam's challenging commitments.

Evolving as a conscientious person on the eve of colonialism and trained as an architect within the posturing of a new nationhood—Pakistan—Islam certainly wondered about the motivation to his work. Although he began work in a government agency in the 1950s, a place not prone to creative work, he was already destined for a greater objective. Instead of an allegiance to the ideology of Pakistan, or to its cultural fabrications that were already turning theocratic in the early 1950s, he opted for a modernist standpoint. He wished to overcome what he encountered as the triple obstacles of that time: the colonial hangover as a continuing Western influence, the blind side of what came to be peddled around as tradition, and the rising tide of a quasi-religious ideology that was overtaking national discourse in that new nation. This is where Muzharul Islam is distinguished from Vidyadhar.

It was clear from his very first projects that Islam would practise as an architect with a clear commitment to the ideological goals and promises of modern architecture. To him, modern architecture was more than an aesthetic trope of the foreign and the new—it was the most viable instrument to bring about a humanist society in the aftermath of colonial disruption. At the same time, Islam was keen on broadening the purposes of architecture. He wished to incarnate the highest ideals of a modern human—rational, ethical, just, without prejudice, dedicated to what Islam would describe simply as "bhadra samaj" (a just and decent society)—in the professional and cultural landscape of a country where, until the 1950s, the modern profession of architecture did not exist, and where, since then, architecture culture remained subjugated to a market dynamic or corporate-commercial entity, and not to mention a cultural amnesia that failed to link contemporary practices with history and tradition.

While he was reluctant to talk about his own work, and averse to theorising, Muzharul Islam adhered to a few principles in regards to his work. We can extract those from his various lectures and conversations. The most evident principle in Islam's work is to see architecture as part of a larger whole. "Now, when we say architecture," he noted, "it does not mean one building – the design of its parts, elements and details – but it means where the building is located, its harmony with the environment, and a decent design of the whole area. This implies, by extension, considering the whole city, the whole village, the whole region, the whole country."

Earlier in 1968, at a conference on architecture, Islam already made clear his stand on his obligations to the larger whole:

"When the activities of man eventuate in the creation of either natural or man-made objects on the surface of the earth, they become the concern of the architect. The architect's traditional activities have been in the realm of small-scale structures, but [he] now feels that without rational and large-scale designing of physical space and objects, it is not possible for him to function fully even within his own discipline." This statement is fundamental in understanding his architecture not as a one-off spectacular thing, but something embedded in a scheme of things, from the social to the economic and environmental. This is certainly the key basis of Islam's architecture.

Since referencing a neoclassical or traditional idiom appeared dubious to Muzharul Islam, the only aspect that seemed enduring is the plain fact of climate. Architecture must respond to the parameters of climate and location which are always there prior to fabrication and manipulation by the human. This is the second principle in Islam's work, and perhaps the more obvious one, leading people to describe his work as climate-conscious, tropical or regional. In this regard, Islam's position echoes the thoughts of writer Humayun Kabir, "In our own country we find how different forms of architecture have been closely linked with the locality. Architecture must be rooted in the atmosphere and the environment."

The third principle defining Islam's work is a tectonic clarity, a clear logic in the way a building is put together and making that expressive through a reductive or minimal application of materials. I have described that expression as being ascetical, that is, without a flourish, shorn off unessential and spectacular elements. I have argued that the significance of Islam's architecture can be found in the "realness" of a building, in the art and mark of construction. The goal of "real" architecture is to gradually filter out everything conditional and extrinsic, to arrive at an irreducible stratum where there is a simple coincidence of appearance and reality—where nothing needs to be qualified by something else.

While Muzharul Islam always spoke in a measured way, there is one term that he used quite frequently, whether speaking about architecture or society in general: bhadra. Bhadra kaaj, bhadra samaj. Decent work, decent society. The notion of bhadra or decent does not easily resonate in the theoretical schema of modern architecture, but in Islam's mind, bhadra kaaj and bhadra samaj were uncompromising goals; they embody an ethical pursuit. I propose this as the fourth principle in Islam' work.

At the centre of his full commitment to Bangladesh, which perhaps superseded the conventional calling of architecture, was the idea of creating a bhadra samaj. Certainly, his bhadra samaj was modelled after socialist principles; it also suggested a distillation of all the best things in Bengal. The apparent plainness in his architecture and the beautiful clarity in his architectural plans are a manifestation of decent architecture.

In describing the character of Amit Ray in his novel Shesher Kobita, Rabindranath Tagore draws a distinction between mukhosh (mask) and mukosri (faciality). In 1993, when I was recording a series of conversations with Muzharul Islam, he abruptly asked me, "Have you read Shesher Kobita?" I am now convinced that Islam was directing me to what he regarded as something decent and authentic. To Amit, describing motivations in literature, masks are represented by fashion and faciality by what is style. Those who maintain their own orientation and authenticity in their work, they define style. "They are distinguished," we hear Amit saying in Tagore's script. But those whose business is to favour the opinion of others in their work, those who are afraid to walk a path different than that trodden by most, they are the upholders of fashion and the bearer of masks.

Muzharul Islam walked a different path than his contemporaries. True to his nature, he remained dedicated to an authenticity that was his own. To some degree, like the character Amit in Shesher Kobita, Islam prescribed a style, if we can call it that. He favoured both a Western and Bangalee comportment, what one might call a cosmopolitanism. He read widely, from Lenin to Rajani Palme Dutt, and from Charles Jencks to Isaac Asimov, was an avid listener of Nazrul and Tagore songs and jazz music, dressed sharply whether in Western suits or Bangalee kurta, remained a little detached from emotional sloganeering, but was unhesitant in mounting sharp critiques of the namby-pamby—of those whose paths are directed by compromises or the flow of the market.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and writer, and directs the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

Comments