President, Presidency and Democracy

The first thing that one needs to remember about our president is that he does not represent the government, let alone the party that selects and later elects him. He represents the state in all its magnificence – the people, culture, history, heritage, etc. The irony is that all of us remember this, except the ruling party of the day. The BNP did not when it ruled, and the Awami League is not doing so now.

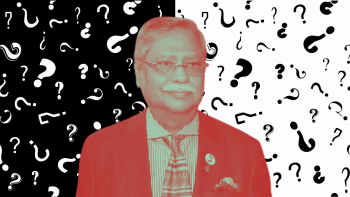

So how does a president balance the interest between the party that elects him and the nation that he represents? How does a president serve democracy with all his obligations being to the party that elects him? Should he reflect the expectations of only the ruling party? What about that of the nation? Should it be just another post to be occupied by the ruling party of the day, without any set criteria? Should all the pomp and pageantry, the protocols, not to mention the expenses on taxpayers, mean nothing more than being an extension of the ruling party?

Questions are endless and the answers, sadly, are partisan. If asked, the rulers will hold us guilty even for asking. The other side will, of course, laud us for exemplary journalism. Until, of course, the roles are reversed. No norms, no ethics, no bigger picture, only partisan considerations – that is how we have compromised most of our crucial institutions, including the presidency.

What we saw in the just concluded election of the president is that the ruling party's parliamentary wing – representing 305 members out of a total of 350 MPs – met and authorised Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to select a candidate on their behalf.

That's precisely what the prime minister did. She made her own selection, kept it to herself and, on the date, just before the submission of the nomination papers, she made it known to a select few – excluding the candidate himself, who said in an interview that he knew nothing till minutes before signing his nomination papers.

We know that everything is decided by our prime minister. As the leader of the House and head of the government, the constitution empowers her to do so – even when it comes to choosing the president. But shouldn't there be a difference between the way a party functionary is selected and the way a presidential candidate is?

Before every party election, the leader is given the sole power by the councillors and delegates to select nominees for every important post. In this case, too, the Awami League parliamentary party did the same, and so did the leader. Should a party position and the occupant of the highest constitutional post be filled in the same manner? Should it be so arbitrary, so narrowly focused, and so personalised?

Our president is the head of state. According to Article 48 (2) of the constitution, he takes precedence above all others. Every act of parliament, every law, every treaty, every constitutional appointment, every year's budget – the list can go on – is sent for his signature to become operative. If that is how "central" this "ceremonial" position is, then shouldn't the occupant of that position be selected with more circumspection?

Then there is the question of the president's "moral authority." Though the position is almost totally devoid of any executive power, it is more than made up by undefined and all-encompassing "moral authority." It is a very significant component of the post. It is an office of prestige, of impeccable credentials, of ethics, of values, and of unquestioned acceptability. Take away the moral authority from the post, and what is left is a cipher. So when we trivialise the process of how we select our presidential candidate, we trivialise that "moral authority" and end up losing a vital element of democracy – the "moral presidency."

A government cannot always be totally moral, but a president has to be. Political expediency is a constant reality of a government. But it can never be that of a president. It does not mean that presidents don't have political affiliations. Mostly they do, but it can never be their sole credential. The "highest protocol" position was patterned to be kept above politics so that if occasions arise, the president can play the part of the "big conciliator." But this he can only do if he enjoys the trust, confidence and "acceptability" of all parties.

The current government is not solely to be blamed for the loss of the "above politics" nature of the presidential post. From the moment Abu Sayeed Chowdhury, the famous jurist and former vice-chancellor of Dhaka University, was replaced by the then Speaker Mohammad Mohammadullah in December 1973, the rot started. The next comparable period starts from 1991 – we skip the period of military-backed governments – when, after winning the election, Khaleda Zia appointed Abdur Rahman Biswas, the newly elected speaker, lifelong politician, holder of many elected posts and a party loyalist, as president.

To Sheikh Hasina's great credit, when she first assumed power in 1996, she tried to restore the traditional neutrality of the president by electing – in face of tremendous resistance from party stalwarts – Shahabuddin Ahmed, former chief justice and former acting president (during the transition from autocracy to an elected government) as the president from 1996 to 2001. It was a bold and visionary move and could have changed the nature of our presidency, and may be of our politics. However, the example was not followed up.

BNP, on the contrary, tried to further consolidate party political hold over the presidency by dragging their own president – Dr Baddruddoza Chowdhury – into controversy on the floor of the House, insulting him and forcing him to resign for faults that were never made public. This killed the possibility of ever having a non-partisan president that Sheikh Hasina's action had sparked. From then on, it was a fast slide down the road of totally partisan presidents.

We write today to underscore how, over the last 32 years, since Ershad's fall and the restoration of democracy in Bangladesh, we have failed to give institutional shape to democracy. One by one, we destroyed or made dysfunctional the institutions that make democracy work: the legislative, the judiciary, the independent constitutional watchdog bodies, the independent media, etc. In a nutshell, there is no accountability system in our whole governance process.

We wrote earlier and we repeat here that the most significant failure – the one that shouldn't have happened at all – is the practical dysfunctionality of parliament. Today, instead of raising the vital questions of public interest, it has been made into a publicly funded platform of government propaganda and denigration of the opposition, even though there is hardly any.

With all other institutions having their roles shrunk, we became a democracy solely focused on elections. And when elections became highly questionable, we even lost that – the one process through which some semblance of accountability could have been ensured.

This daily headlined yesterday that the government may go for inclusive polls this time around. We really hope so. However, the way our new president was chosen, and the publicly announced reasons for choosing him – his long-standing and unwavering party loyalty – have further pushed that possibility into question.

Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments