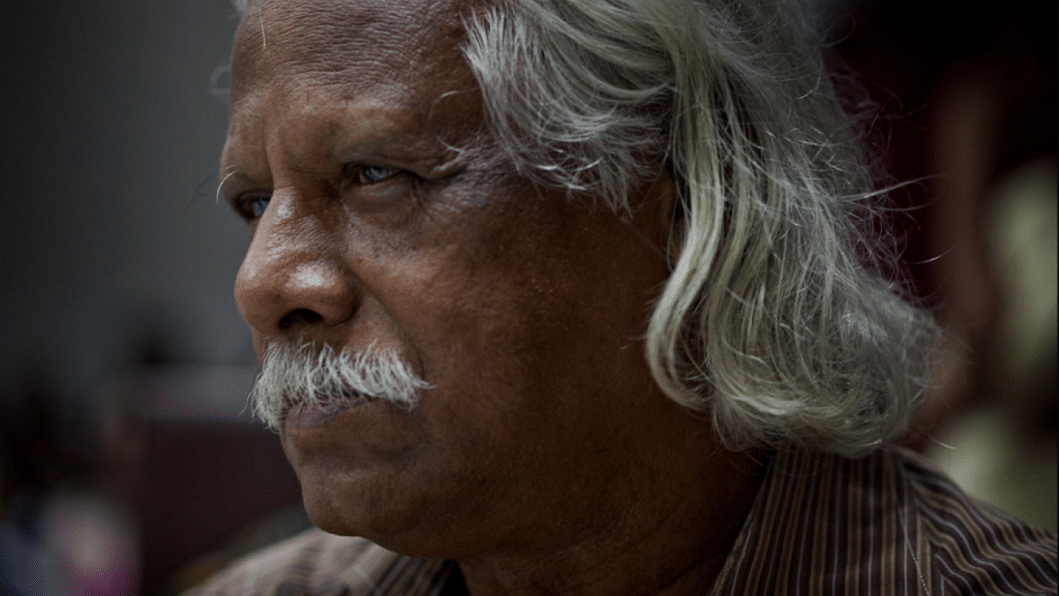

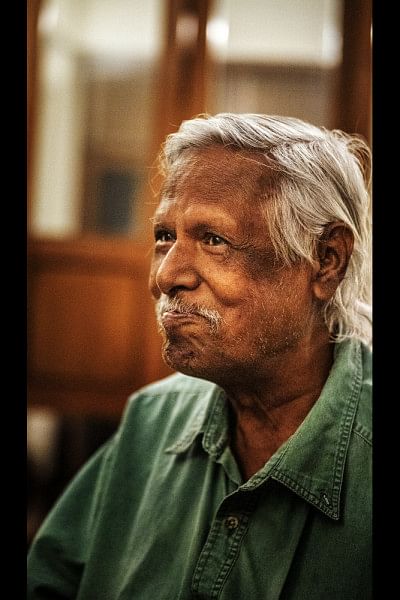

Radical pragmatist, champion of women, public-health advocate

I often think of Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury when I am about to fall asleep riding in a car. This has been my habit for more than 50 years, reminded of how he would immediately fall asleep in the front passenger seat during our many hours travelling in Bangladesh.

That said, like the dreaded knock, I was afraid that one of my friends would one day ask me to write something about him, a memorial, when there are literally millions in Bangladesh and around the world whom he touched – in body, mind and spirit.

Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury, the pioneering physician who founded the Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK), people's health centre, in Bangladesh passed away April 11, 2023, after several months of illness. It is fitting that he spent his last days at Gonoshasthaya Nagar, the large urban hospital he founded in Dhaka, lovingly cared for by GK staff. He was 81.

Many are paying tribute to him in Bangla, the language in which he so effectively used to speak truth to power.

"Zafrullah always tells the truth," my adopted Bangladeshi sister, a highly intelligent woman with limited education, told me after watching one of his frequent appearances on television.

So maybe that should be item #1, his courage.

Shattering barriers

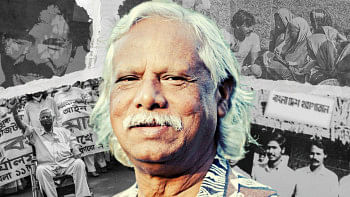

Zafrullah's truth-speaking was closely tied to his thirst for knowledge. Besides being a voracious reader, he absorbed information from a wide range of partners inspired by his dedication. He could see past social constructions to the essentials. Gonoshasthaya Kendra actively challenged patriarchy, shattering barriers to women's employment.

The GK experiment proved that women, even the poorest, with support and training were as capable of performing work that previously was limited to men. Confident women doing remarkable things in an atmosphere free of sexism and gendered hierarchies was central to Zafrullah's vision.

As a radical pragmatist, he recognised that if paramedics rode bicycles, they could more efficiently reach the communities they were serving. Despite loud objections from religious conservatives, GK pioneered women riding bicycles in Bangladesh. On May 1, 1977, International Women's Day, confident GK women cycled 25 miles from the health centre in Savar to Dhaka.

Breaking the bicycle barrier was only the beginning. Zafrullah insisted that women drive cars! As a result, the vast majority of GK drivers are women – a defiant exception to the gender bias overwhelmingly prevalent in Bangladesh today. Driving in Bangladesh is not for the meek, yet one always feels confident with GK drivers weaving through the chaotic traffic.

The GK campus in Savar, now a sprawling complex, began on barren lands with just a few health workers living in tents. Security has been an ongoing concern from the beginning. This was an area rife with bandits and the GK workers were robbed more than once. Who but Zafrullah would have insisted that women be put in charge of security! Strong and confident, they oversee access and secure the grounds. Women security guards seem as natural at GK as they are unheard of elsewhere in the country.

Radical pragmatism

While the seeds of Zafrullah's radical pragmatism were sown out of necessity during the war, they grew and flowered on the soil of independent Bangladesh. Women became paramedics performing surgeries with lower infection rates than doctors. They worked as supervisors, pharmacists, drivers, security guards and metal workers. They ran small-scale manufacturing and factories as they learned new skills, taking on ever higher levels of responsibilities.

Gonoshasthaya Kendra pioneered numerous innovations in healthcare delivery including the introduction of community health insurance. Contributions were on the basis of income and resources such as landholdings. Wealthier people pay higher premiums and the poor pay little, but all receive quality, comprehensive health care.

Zafrullah successfully fought against pharmaceutical colonialism by forging the National Drug Policy. Prior to the policy, a few multinational companies held a stranglehold on the manufacture and distribution of medicines while promoting costly, wasteful and irrational drug combinations. While the National Drug Policy enabled the development of Bangladeshi drug manufacturing, Zafrullah also oversaw the creation of Gonoshasthaya Pharmaceuticals, the GK production facility producing low-cost drugs.

The evolution of GK over the last 50 years is a credit to Zafrullah's boundless energy, imagination and vision. When Zafrullah saw a problem, he sought solutions. Gonoshasthaya Kendra now serves more than a million people throughout Bangladesh including a large urban hospital in Dhaka providing affordable hemodialysis, burn treatment and plastic surgery, physical therapy, ophthalmology, emergency care and Ayurvedic medicine among other specialties. There is an outstanding medical college, Gonoshasthaya Samaj Vittik Medical College, and the large university, Gono Bishwabidyalay located in Savar.

Zafrullah inspired health activists around the world. He was central to the creation of the People's Health Movement involving health workers from more than 70 countries. Thousands from more than 90 countries had come to Savar to share their thoughts and insights at two People's Health Assemblies on the GK campus.

A perfect match

Thinking about what to write while walking alone in the woods near my home in Vermont, I was touched by the realisation that to talk about Zafrullah's life requires acknowledging Shireen Huq, a tireless champion and leading voice for women's rights. I remember the delightful surprise of seeing Shireen and Zafrullah together in 1992, having known them individually. I'd often tease them by saying, "Shireen, how could you marry such a man?" But in reality, they were a perfect match, strengthening one another.

During his final weeks Zafrullah was still thinking of the work that needed to be done. Having been a champion for maternal and child health for more than 50 years, he said we must think about old people and what must be done for the ageing population of Bangladesh. Had he lived longer, I could see him finding new ways to approach geriatrics and eldercare.

Back to the issue of me falling asleep in the car while thinking of Zafrullah – he was tireless and often only afforded himself the opportunity to sleep when going somewhere. His work ethic deeply impressed me and so many dedicated GK workers.

Although his absence after such a long struggle still seems unreal, I am certain that over time, consciously or unconsciously, our connections with him will grow even stronger.

Steve Minkin is a researcher, historian and language interpreter who speaks Bangla and has been a friend of Bangladesh since the independence war in 1971 when he was an activist in New York. He has worked on floodplain ecology, public health and nutrition in Bangladesh over five decades. He lives in Brattleboro, Vermont, in the United States.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments