How a rickshaw-puller changed the course of Dr Zafrullah’s life

"Should I go back to the UK? If I can't serve my countrymen, I might as well go back."

These were the thoughts of a disillusioned Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury in the year 1972. His chosen name for a hospital and the option for overseas funding had been rejected. The young nation's bureaucracy was creating hurdles at every step.

As a freedom fighter, Dr Chowdhury, along with his comrades had fought hard and made many sacrifices to free their country. But all that seemed non-consequential in the free country if he could not work for its development. Many of his friends had already gone back to the UK. He was dejected and disappointed.

It was during these days of feeling desolate that he met a rickshaw-puller whose words changed the course of his life forever. During their conversation the rickshaw-puller asked, "Sir, why do you seem so depressed?"

Dr Chowdhury: "I came back from the UK. During the Muktijuddho, we established a hospital and gave treatment to the Muktijoddhas. But I can't do the same in the free country. I might have to go back to the UK. This thought is making me sad."

Rickshaw-puller: "Sir, you can afford to leave. You came from the UK, you can go back there. We are stuck here. What will happen to us? Won't you think about us?"

These words deeply affected Dr Chowdhury. Was he being an escapist, he chided himself. The simple mannered rickshaw-puller had forced Dr Chowdhury to ask himself a lot of questions.

In a way, this is how Dr Chowdhury "found his way back". He ditched the UK plans and started concentrating on the work at hand.

He met Bangabandhu. Bangabandhu initially argued that large hospitals should be set up. However, Dr Chowdhury disagreed, and mentioned, "No, Mujib bhai. We should start from the villages. Only an enlightened rural population can ensure the overall enlightenment of Bangladesh."

Upon hearing this, Bangabandhu became silent for a while. Probably his logic made sense to the great leader.

Dr Chowdhury added, "We set up the 'Bangladesh field hospital' in Bishramganj, Agartala during the Muktijuddho. We want to set up a hospital in Savar with that same name, but the bureaucrats are not allowing us to do so."

Bangabandhu replied, "This seems a bit too official. Please choose another name." The naming debate went on for a while.

Zafrullah explained that he was emotionally attached to the name but Bangabandhu remained unyielding.

"Why don't you do this," said Bangabandhu, "pick three and I will also pick three names. Let us meet again another day."

A few days later, Dr Chowdhury came back to see Bangabandhu with three names.

"So, what name did you pick?"

"Bangladesh Field Hospital."

Bangabandhu cut him off , "No, not that one. Give me another one".

"Gonoshasthaya..."

"I had said Gonoshasthaya but Bangabandhu heard 'Jonoshasthaya'"

"Yes, yes, not Jonoshasthaya, Gonoshasthaya, keep that name for the hospital."

Bangabandhu managed to acquire 30 acres of land in Savar for the Gonoshasthaya Kendra. What was a tent-based medical centre in 1972, had spread its wings over a period of time and reached other parts of the country. He established Gonoshasthaya Nagar Hospital and didn't forget the words of that rickshaw-puller. Gonoshasthaya Kendra ended up being a trusted name all across cities and villages for the poor and the needy.

Unquestionably, Dr Chowdhury's goal in life was to serve the poor people of his country. The Liberation War had profoundly affected him. He spent his entire life mending and wearing the same torn shirts over and over. One day, I jokingly asked him, "What would Gonoshasthaya Kendra's assets be worth?"

"A few thousand crore taka," he replied nonchalantly.

"Such a vast amount of wealth exists, but none of it belongs to you. Neither you, nor your wife, children or family members own it. Does this thought ever cross your mind? Does it make you unhappy?"

He chuckled and replied, "No. What will I do with wealth? I don't need it."

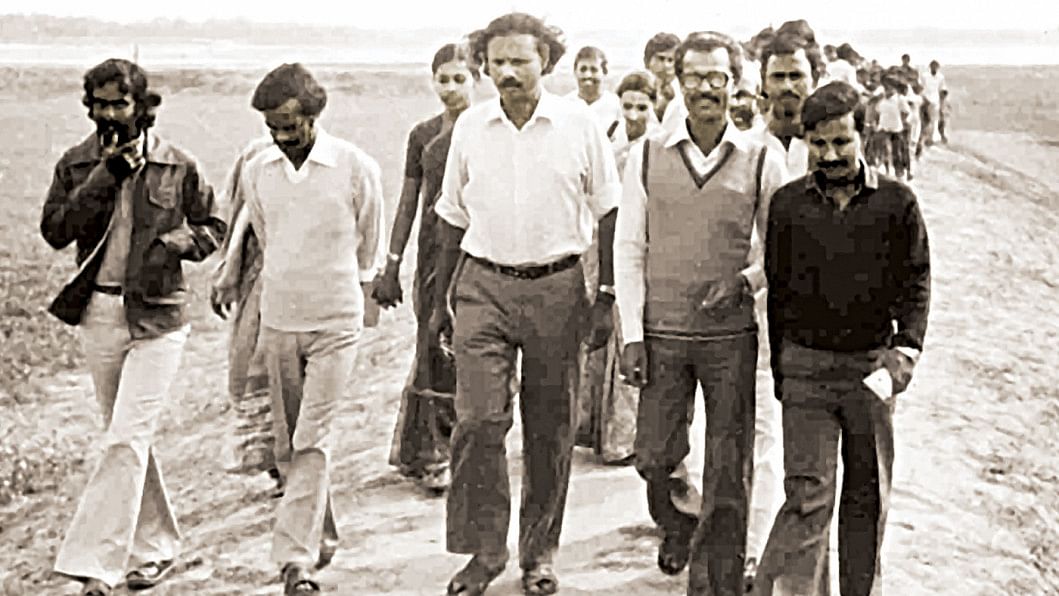

He had gone to London to study medicine. He led a fairly privileged life. After completing his studies, he could have remained in London or gone to any developed nation to practice medicine. Instead, just a few days before his final examination, he tore up his Pakistani passport. It was during the initial days of Muktijuddho. He did not sit for the examination and managed a travel permit and started his journey towards India. On the way, the Pakistan government tried arresting him in Syria. However, one cannot be arrested from an aircraft; moreover, he was not using the Pakistani passport to travel. He somehow escaped and eventually reached his motherland where he set up a field hospital to treat the wounded Muktijoddhas at Agartola's Bisramganj. The hospital had 480 beds.

Gonoshasthaya Kendra is a transformed version of this field hospital.

The main objective behind establishing the Gonoshasthaya Kendra was to ensure the healthcare of the poor population of the recently freed nation. That is why he established it in Savar instead of Dhaka.

Dr Chowdhury was a man ahead of his time. Since 1972, Gonoshasthaya conducted all monetary transactions through banks. They preferred not to have cash transactions.

He was also a great advocate for empowering women and believed that this was a key factor in the development of a nation. Today in 2024, the sight of a female riding a bike raises eyebrows, but Dr Chowdhury started training female drivers way back in 1972-73.

He gave them jobs driving jeeps on the Dhaka-Aricha highway. He also developed and trained young women in many other occupations such as in electric work and painting, etc. He even trained them in a few unconventional occupations in Gonoshasthaya with the mantra: there's no work that women can't perform.

From the very early days of Gonoshasthaya's operations, Dr Chowdhury took initiatives to bring the most poor and vulnerable people under health insurance at minimal fees. It was a successful venture. His dream was to bring all impoverished individuals under the health insurance umbrella. He tried to convince the government in this regard, but in vain. Still, he never gave up -- he continued to devote all his efforts to establishing health insurance in his hospitals.

Another groundbreaking initiative of his was to enact the 1982 drugs (control) ordinance in 1982 during HM Ershad's government. The development of the medicine sector in Bangladesh can be solely credited to this ordinance. Before this, the medicine market was dominated by multinational companies (MNCs), which produced 70 percent of medicines. At the time 1,782 kinds of medicines were being imported. After the ordinance was passed, the number came down to 225, and eventually, it is now at minimal levels.

Currently, 97-98 percent of the demand is being met through local production. Our locally produced medicine is cheaper than many other countries. Dr Chowdhury worked hard to keep the medicine prices low, and he believed that it was possible to further lower the price levels. As part of this effort, he established Gonoshasthaya Kendra pharmaceuticals.

However, the pharmaceutical owners in the country often refuse to acknowledge Dr Chowdhury's contributions towards the development of this industry -- simply because he fought to reduce the price levels. Interestingly, some doctors of the country opposed the enactment of the medicine ordinance. At that time, Bangladesh Medical Association (BMA) cancelled his membership.

Dr Chowdhury is known for his tireless work for the people of Bangladesh even when he became ill with both kidneys becoming damaged. He had to go through dialysis thrice a week. Each session was four hours long. But this did not stop him from his work. He established the largest and the most modern kidney dialysis centre at the Gonoshasthaya Kendra hospital, where more than 100 people could get dialysis simultaneously. Even here, his main target was the poor. Not only at a discount, people who could not afford even the discounted fee could get their dialysis for free.

Dr Chowdhury used to work and converse with others while going through dialysis. Most of his quotes in this writeup came from a discussion while he was going through dialysis on March 5, 2021. He left us on April 11, 2023. After his passing, Professor Serajul Islam Choudhury said, "Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury was dedicated to not only treating human beings, but he also treated the society as well."

No words could describe his dedication to the welfare of the poor better.

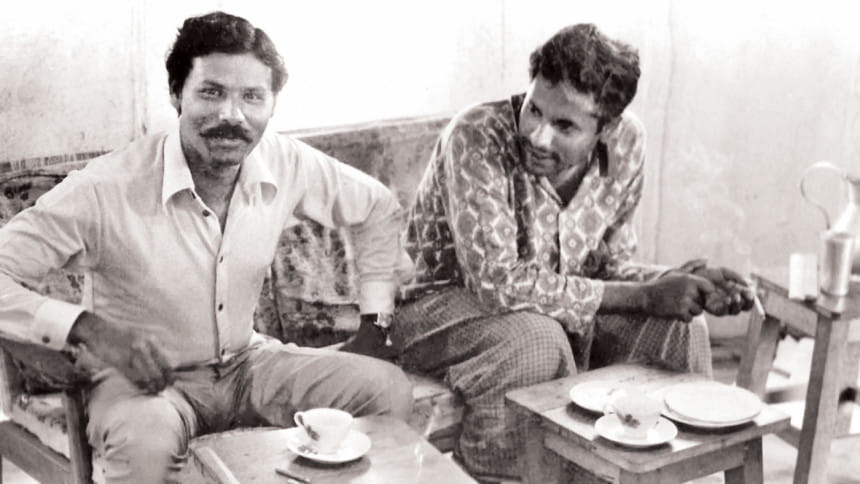

Famous film developer Alamgir Kabir made a biopic on Dr Chowdhury named "Mohona", which was released in 1982. I asked Dr Chowdhury whether he had seen the movie or not. He smiled and replied in the negative.

"Many individuals told me about the film. In the film, it is shown that we went back abroad. But we never did that. The rickshaw-puller did not allow me to leave. I stayed back for the rickshaw-pullers."

(Translated by Mohammed Ishtiaque Khan from Bangla)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments