A revolutionary’s journey

The first time I saw Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury was in 2007, for a story in our weekend magazine in The Daily Star, on his Nagar Hospital on Mirpur Road, where anyone, no matter how poor could get medical care at subisidised costs. I was not expecting to see a clean, organised, fully-equipped, seven-storey hospital where patients could see a doctor for a mere Tk 20. The place was busy but organised, not chaotic like our understaffed, overcrowded public hospitals. Strikingly apparent was the presence of mostly female staffers -- the receptionist, paramedics, pathologists, nurses, on-duty doctors, and even the drivers of the hospital vehicles. Among the patients were labourers, domestic workers, teachers, civil servants and beggars. It was the first time I heard that patients could get an insurance card -- for Tk 150. Insurance holders did not have to pay to see an on-duty doctor, and to see a specialist the fee was only Tk 200. The most innovative part of the insurance scheme was that it was designed to provide healthcare to people according to their ability to pay. So, for someone who was destitute, the treatment would be free, for a poor person, it would be highly subsidised, for an upper middle-class person the cost would be higher. It was hard not to be floored by the foresight of the individual behind what seemed to me, a fantasy world where poor people had access to affordable, efficient medical attention.

But that is what Zafrullah Chowdhury is -- a larger than life figure who had the vision to realise that it was the lack of access to affordable healthcare that condemned the poor to a life of continuous ill health. His fierce determination to break this vicious cycle led to the creation of an institution like Gonoshasthaya that has made revolutionary changes not only in healthcare but in public perception of women as vital nation builders.

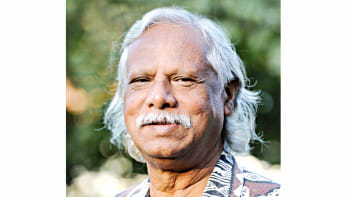

When my team and I went to interview him at the hospital, I was a little taken aback by his appearance; longish white hair and clad in a batik Hawaiian shirt and khaki trousers, sandals half worn, he looked more like an eccentric artist than the founder of a mammoth development organisation. It was hard to gauge his mood as he went on his inspection of the wards, blasting the nervous staff at the top of his voice for some inefficiency and then suddenly cracking a joke to make them laugh, his hawkish eyes twinkling. His staff called him Boro Bhai, no "sir" or "doctor" for this no-nonsense man. But the respect and love he evoked among patients, paramedics, doctors and the staff, was obvious.

And when he met patients, he was extremely gentle and kind.

At present, Nagar Hospital has among other facilities, a burn and plastic surgery unit, cardiac unit, dental unit, surgery, counselling, physiotherapy, Ayurveda, Yoga and of course 24 hour emergency services.

So how did a vascular surgeon looking towards an ascending medical career in the UK end up being the founder of a multidisciplinary organisation in his home country that would be committed to the welfare of the poor and marginalised? The Liberation War of 1971 changed the trajectory of his life. He and his friend Dr MA Mobin left their studies in London to join the resistance by treating wounded freedom fighters. It was pure patriotism that laid the foundation for Gonoshasthaya Kendra. Zafrullah and his fellow doctors set up a 480-bed field hospital near the border with India to treat the wounded and sick. The young surgeon realised that while there were doctors in this hospital, the facility didn't have any nurses. So girls and young women in the refugee camps were invited to learn first aid and assist in operations.

"I realised that it was not the amount of training that was important in this context but the access to training," he said during the interview. When the war was over, the Field Hospital was renamed Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK) which relocated to Savar with sub centres in surrounding areas and other districts. From his experience at the Field Hospital, Zafrullah knew how he could build a team of paramedics. GK started training girls and women who had completed their SSC (Secondary School Certificate). Soon it was a common sight to see these young women in the villages, going on foot or bicycle to visit households, telling them about basic healthcare, sometimes giving vaccines, even assisting in deliveries. The presence of these female paramedics gave women a new status. Villagers began to realise their importance and appreciate their work. GK's involvement with the community had a major role in the success of national family planning, immunisation and ORS campaigns.

Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK), which is a multidimensional development programme, involves the community as a whole. It includes projects ranging from primary healthcare centres and hospitals, community schools, agricultural cooperatives, women's vocational training centres, training women drivers, to economic enterprises to help finance GK Trust activities. But GK's most obvious success is its primary healthcare programme (mainly in the villages) that benefits over a million people.

GK has proved that primary healthcare can be a successful, sustainable system. In 1982, GK's pioneering effort in forming a National Drugs Policy allowed local companies to produce essential drugs at much lower prices than multinationals did. GK itself produces essential drugs at subsidised prices. GK's Gono Bishwabidyalaya (People's University) trains doctors, paramedics and physiotherapists who will provide primary and tertiary care to poor communities.

The accolades he has received are many. Among them are a 'Certificate of Commendation' for his contributions during the Liberation War in 1971, the Swedish Youth Peace Prize, Sweden for founding Gonoshashthaya Kendra and providing primary healthcare to rural communities, Maulana Bhashani Award, Ramon Magsaysay Award, The Right to Livelihood Award, Sweden, One World Action Award, UK, Public health Heroes Award, UK, Fr. Tong Memorial Award, India, Doctor of Humanitarian Sciences Award, Canada.

His undeterred commitment to the welfare of the disadvantaged was probably because of his unconventional upbringing. His mother, Hasina Begum, a courageous, self-educated woman, who believed in the equal rights of women and men, taught him the value of sharing with the less fortunate. His father, Humayan Murshed Chowdhury, was an honest police officer and instilled in him love for one's motherland. Zafrullah found his perfect match in his life partner Shireen Huq, a passionate human rights activist and one of the founders of Naripokkho, a women's rights organisation. Their children are Brishti and Bareesh.

The basic philosophy that Zafrullah modelled all his endeavours on was to come up with indigenous solutions for all problems. Thus Gonoshasthya's mission was to 'go to the village and build the village'. The GK Savar hospital serves the community and provides all the medical services as well as alternative medical treatment such as ayurveda and acupuncture.

In fact, he has been unequivocally, an advocate of local medical expertise. In 2019, GK inaugurated its second dialysis centre in the Savar hospital, the largest such centre in the country. During the pandemic, he tried to popularise a locally made antigen testing kit and was ready to help set up a 2,000-bed Covid hospital which did not receive the support it warranted during the most challenging moments of the crisis. For his own treatments which included regular dialysis he would come to his hospital even when he was on life support. There are few individuals who can display such conviction of their own principles.

Considered at times a controversial figure for his incendiary remarks in public, he remained unapologetic and brutally frank all throughout, a fighter till the end. Battling with formidable ailments, waging a war against crippling poverty and ill health of people, to bring some solace to the most vulnerable and neglected, his contributions to this country cannot be listed within the confines of this article.

[Some information has been taken from Star Weekend Magazine, published on November 30, 2007]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments